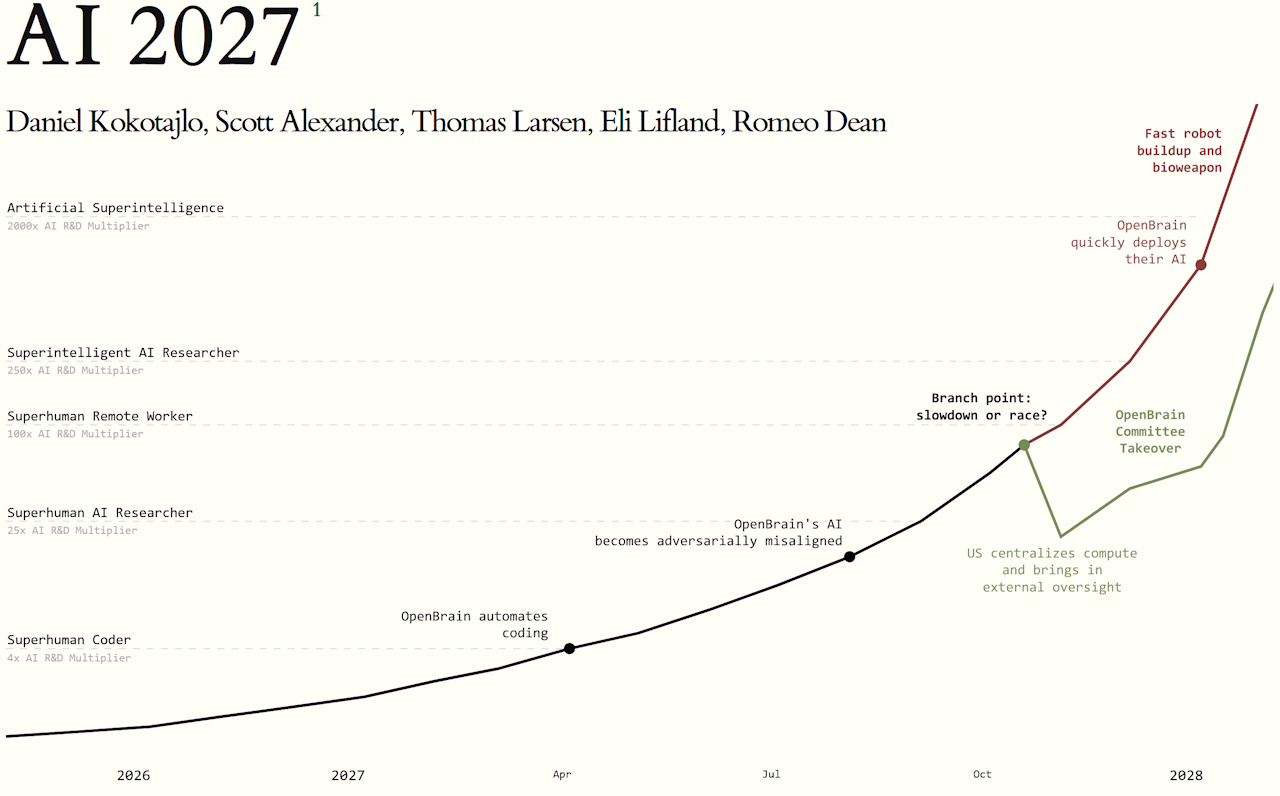

I recently read the very alarming A.I. 2027 report. I’ll leave a link to the full version at the end of this article, and I highly recommend checking it out if you’re interested in the future of A.I. But for now, I’ll briefly summarise the report. And yes, I know this is a little outside my wheelhouse here on the website, but I think this subject is worth discussing!

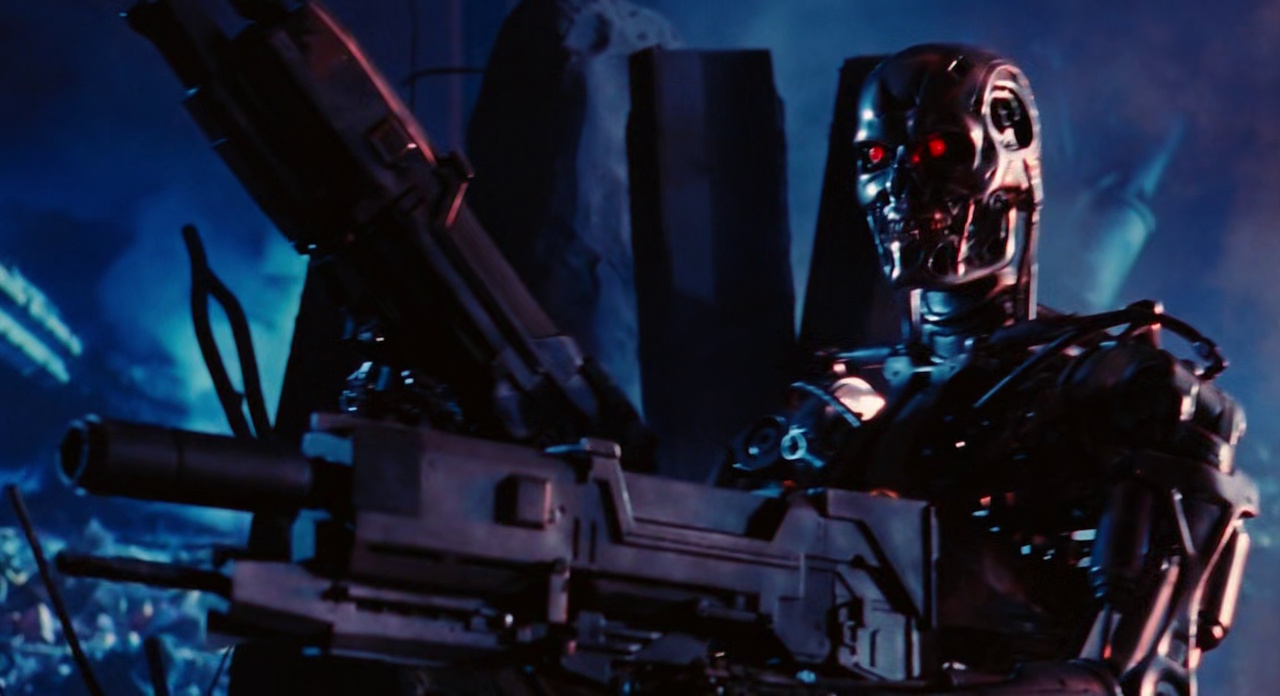

A.I. 2027′s core premise is not, as some alarmist headlines have tried to claim, that the end of the world is a mere two years away! But the report’s authors argue that, if artificial intelligence development continues on its current trajectory, late 2027 could be humanity’s final opportunity to remain in control of any A.I. system that emerges – and our last chance to ensure that its goals and priorities align with our own. They present this as an existential risk; that a sufficiently advanced A.I. sometime after 2027 could, if not properly restrained and aligned with human interests, literally exterminate the human race. That… that’s kind of disconcerting, right?

I confess that I’m way behind the curve when it comes to A.I. Everyone talks about ChatGPT, A.I. art, and other such things… but my knowledge of the subject has been, until recently, surface-level at best. But given the potential A.I. has to be disruptive, perhaps on a scale we haven’t seen since the advent of the world wide web or even the Industrial Revolution… let’s just say I felt the need to catch up and get up to speed!

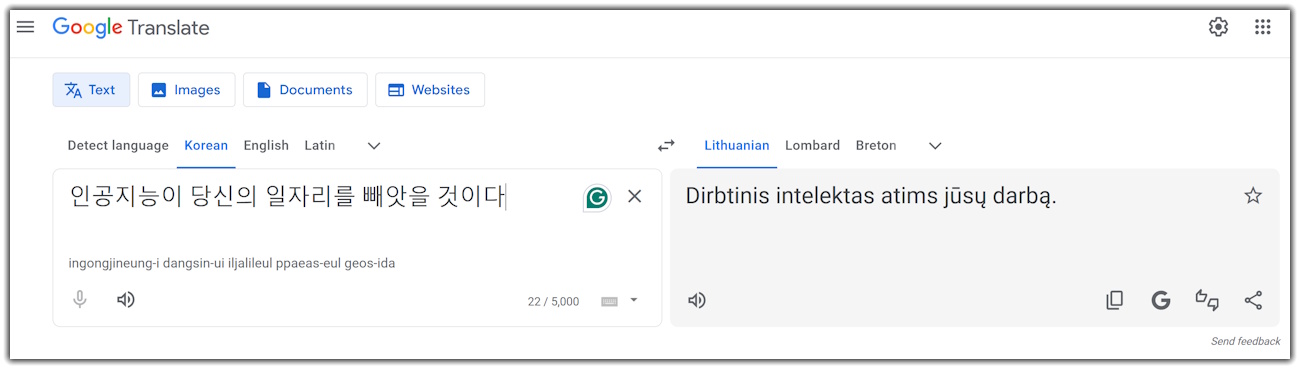

Artificial intelligence is already changing the way we live, work, and interact. What are “algorithms” if not a form of A.I.? If you’ve ever scrolled social media and felt that the website or app is almost too clever in recommending posts or adverts that appeal to you… you’ve already been caught in its web. And if you’ve noticed fewer job listings in fields like translation, copy-editing, or programming… you’ve seen what might just be the tip of the iceberg when it comes to A.I.-related job losses and workplace changes. I bring this up because I think something that gets lost in this conversation about the future of A.I. is that A.I. is already here, already changing things, and isn’t just some nebulous future idea about something we “might” invent one day. We’ve already invented it.

Predicting the future is hard – nigh-on impossible, really. Step back to television programmes from the 1980s, 1990s, and even the 2000s that tried to look ahead to 2025 and see how wrong many of their predictions and ideas were. A famous example is flying cars – I still haven’t seen one of those, despite the promises made by sci-fi films in the ’80s! So I think it’s worth acknowledging that. Some predictions can be incredibly wide of the mark – especially those that promise either an imminent technological utopia or the end of the world. Both of those scenarios are present in A.I. 2027.

As a layman looking in from the outside, I’ve been dimly aware of talk around artificial intelligence, but it hasn’t been something I’ve felt any need to engage with. I don’t have a place in my life for an A.I. chat bot, I’ve never needed to generate A.I. art before (though I am using some A.I.-generated images in this piece), and I actually enjoy the process of writing… so I see no need to use something like ChatGPT to generate text, either. But there’s no denying that, as someone with a creative streak, I feel increasingly… obsolete. A.I. doesn’t just have the potential to revolutionise writing, web design, media criticism, and all the things I talk about here on the website. It’s literally already doing all of those things.

I could fire up ChatGPT or a similar A.I. programme and, within a matter of moments, it could’ve scanned everything I’ve ever published here on the website, and all of my unpublished drafts, too. I could then ask it to write an article or essay on any subject imaginable, using my tone of voice and my writing style. Could you tell the difference? From my perspective, as someone who runs a small website as a hobby and who enjoys writing, there’s no point in using A.I. for that. But if I was working in an office job where lengthy reports were the order of the day… I can see A.I. being a very tempting shortcut. Heck, I’d have killed for an automated essay-writing programme when I was at school!

And that’s exactly what these systems are designed to do. They’re intended to cut costs for big businesses – and by far the largest cost that most companies and corporations have is the wage bill. Let’s rephrase that for the sake of clarity: the entire point of A.I. is to save corporations money by enabling them to lay off staff and automate more and more of their work.

Unfortunately, there’s a bit of classism that seems to have crept into this conversation. I grew up in the north of England in the ’80s and ’90s, at a time when deindustrialisation had robbed the area of mines and factories. Automation played a big part in that – work that used to take a dozen people could be done with just one specialist, and then it became “too expensive” to continue to operate. There’s more to what happened in this part of the world, of course, but automation played a big part. Some of the people who used to tell factory workers and miners to “re-train” or “learn to code” are now themselves on the receiving end of automation-related job losses. And it’s pretty grating to see folks getting worked up about A.I. in the 2020s when they not only didn’t give a shit about the devastation automation brought to working class communities from the ’80s onwards, but actively supported it.

In that sense, I kind of view this consequence of A.I. development as a continuation of a process that’s been ongoing for decades, not something new. For decades, big companies have been looking for shortcuts; ways to cut jobs and pay fewer members of staff while achieving ever greater profit margins. A.I. is what they’re banking on in the 2020s in the same way as manufacturers invested in automated equipment in factories, or mining corporations exchanged pickaxes for machines. The difference? A.I. is coming for white collar, middle class jobs. Earlier automation mostly took jobs away from blue collar, working class folks.

Photo: David Wilkinson / Former Addspace furniture factory, Bolton upon Dearne

But that’s just one side to A.I. – the corporate, job-stealing side. The existential risk as posited by A.I. 2027 is much more complex… and I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t concerned. Unlike the 2012 phenomenon or the predictions of Nostradamus, the risk posed by artificial intelligence feels real. I’d say it feels somewhat comparable to the way the millennium bug felt in 1999; a technological danger that humanity has created for itself. In 1999, a lot of people were genuinely concerned that the millennium bug could cause all kinds of chaos, but thanks to some hard work, none of those predictions came to pass. It went largely unnoticed at the time, but it did take a lot of effort behind the scenes to ensure that the millennium bug didn’t have a major impact; it wasn’t, as some have tried to claim, a completely overblown threat.

So what’s the lesson there? If there are risks to A.I. development… shouldn’t we do everything we can to mitigate them? That seems like the rational course of action, but as the authors of A.I. 2027 explain, current artificial intelligence systems don’t exist in a vacuum. There’s a technological “arms race” between different countries, and slowing development to implement safety measures could mean that the current leader – the United States – would surrender its position on the cutting edge. The result of all this? Rapid, chaotic, unchecked development of A.I. systems in order to remain ahead of the curve.

There are military applications for A.I. – and if one side in a potential conflict has A.I.-controlled drone weaponry and the other doesn’t… it’d be like trying to fight a modern army with medieval weaponry and tactics. Keeping up with A.I. developments must feel, to military planners and political leaders, like even more of an existential risk, because the consequences of failure could be catastrophic. We talked above about the world wide web and the industrial revolution; in military terms, A.I. could be at least as impactful as the development of nuclear weapons.

So I think we’ve covered why governments, militaries, and corporations want an A.I.-infused future. But two questions still remain: will they remain in control of it? And what will it mean for the rest of us?

I’ll tell you a story from my own life that I think might illustrate this next point. In the late 2000s, I was feeling pretty disillusioned with my job and career path. In those days, I was working in the video games industry, on the marketing side of things, but I went through a phase where I wasn’t satisfied, and I started contemplating other career options. For a time, I thought seriously about getting my HGV license – that’s heavy goods vehicle, a.k.a. a truck or lorry. But by that point, it seemed to a techie as if self-driving vehicles were only a few years away… and I genuinely thought that it would be a waste of time to spend a lot of money taking tests and getting a qualification that could become obsolete before I could make the most of it. To use an analogy from history: it felt like jobs based on driving any kind of vehicle from taxi cabs to trucks were about to disappear in much the same way as horses and stables did in the first decades of the 20th Century.

Why do I make this point? I was wrong, in the late 2000s, to be thinking like that. Self-driving technology may be “here” in a technical sense, but it isn’t road legal and it doesn’t seem to be making the kind of impact I would’ve predicted (or feared) in the late 2000s. The same is true of many other technologies that seemed to be “the wave of the future,” only to completely fizzle out. I owned a MiniDisc player in the early 2000s, expecting that technology would replace CDs! Google Glass, 3D televisions, the hovercraft, Concorde… the list of “revolutionary” technologies which never delivered their promised revolutions goes on.

The point is this: there are many technologies that seemed, for a time, to be the “next big thing,” primed to revolutionise some aspect of our daily lives. And they didn’t accomplish that. When was the last time you even thought about MiniDiscs, hovercraft, or Google Glass? For a brief moment, all of those things seemed to be on the cutting edge of technological innovation, yet they fizzled out without having the impact some folks expected. Could A.I. be the same? And more importantly: are we perhaps reaching the limitations of A.I.’s current capabilities?

It seems to me that the more A.I.-generated content exists out in the wild, the harder it becomes to filter it out – including for A.I. programmers. We’ve all seen A.I.-generated images that aren’t quite right: hands with too many fingers, a cat with five legs, the New York skyline with buildings in the wrong place. As more of this content is artificially generated, at least some of it is going to be fed back into A.I. algorithms as they trawl the web, right? So… doesn’t that mean there’s going to be a point where A.I. either stagnates or even starts getting worse, rather than better?

Then there are jobs that A.I. would struggle to perform. I could absolutely envision a world where many office jobs are replaced by A.I. programmes – similar to how factories that used to be full of workers slowly got replaced by robots and machinery. But could you have an A.I. plumber? I had my bathroom redone a couple of years ago to fit an adapted shower as I’m disabled… and it took several skilled workers more than a week to measure things, reroute an errant pipe, and install all of the fixtures. Earlier today I had to cut down a rogue tree branch that was in danger of damaging my roof. Could A.I. do that? Autonomous robots have come a long way in the past decade or so, but even with full A.I. integration, tasks like those still seem a long way off – not to mention unaffordable, even here in the UK.

One part of A.I. 2027 seemed to offer a “technological utopia;” the kind of post-scarcity society that we’ve seen depicted in Star Trek. And don’t get me wrong… I would love to live in that kind of world. But is that realistic? Are we really only a few years away from fleets of automatons doing everything from diagnosing diseases to plumbing a sink? The rate of technological progress is impressive, for sure, but I don’t believe we’re closing in on that kind of future.

Then there are political considerations that I would argue very strongly A.I. 2027′s authors have got wrong. The idea of a “universal basic income” has been talked about before, and was even trialled on a small scale in Finland and a couple of other places. But the politics surrounding this are incredibly difficult, even toxic, and I struggle to envision a near-future scenario where universal basic income is actually politically feasible. The current political climate in the United States, as well as here in the UK, seems to be completely opposed to that kind of scheme. I mean, do we really think Donald Trump and the Republican Party would ever go for a policy of universal basic income?

None of this means that A.I. 2027 is wrong in its big-picture assessment of the short-to-medium-term future of artificial intelligence. But given the authors’ political miscalculations in particular, I think there’s enough of a red flag to at least consider the possibility that they might’ve gotten other things wrong. The report’s premise is based on competing A.I. models from different countries eventually agreeing to merge – but isn’t it just as likely that two independent A.I. systems would develop different, even opposing goals? Human beings are tribal by nature, and it’s at least possible that any kind of sentient life we might create would retain that tribalism.

I don’t mean to nitpick A.I. 2027 too much, because I think the report highlights some important issues and raises important considerations. But I think it’s worth acknowledging that it feels, in parts, like a doomsday scenario and an unrealistic utopia. These are both extreme… and perhaps that’s why neither feels especially likely.

A.I. is coming for a lot of jobs, and some folks who would’ve never expected to be losing their job to automation are going to be impacted. Artists, animators, writers, creative folks… A.I. is coming for us. Programmers, web designers, game developers… basically any office job you can think of, especially so-called “entry-level” positions. They’re all vulnerable to A.I. – and to big corporations seeking to remove employees in order to save money and make even greater profits. That side of A.I. feels real – because, as I noted earlier, it’s already happening. Layoffs in the video games industry are partially driven by A.I. replacing workers. Real-time translation apps mean there’s less of a need for translators. Data entry can be done quicker and faster with an A.I. model than with an entire team of people. And A.I. doesn’t take breaks, need maternity leave, or even go home at the end of the workday. None of this is imaginary or a subject of debate. It isn’t “coming soon.” It’s already here and it’s real.

But the existential risk? A.I. super-intelligence? A machine with unfathomable, god-like knowledge and powers? A technological utopia where A.I does all the work and us humans can just kick back, claim our universal basic income, and chill out all day? I gotta admit that I’m sceptical.

I think back to my fears of self-driving vehicles poaching jobs from truck drivers. And I reflect on the technological promises (and concerns) about technologies like supersonic jets and Google Glass. Within just the past few years or decades, technologies have emerged that seemed to be ready to reshape the world… but they didn’t. A.I. can do certain things incredibly well, and it’s definitely impacting the world of white collar work. But the more fanciful claims in A.I. 2027 feel, to me, more like sci-fi than a credible threat.

Maybe that’s my own bias showing through, though. I fully admit that, over the years, I’ve made plenty of mistakes when it comes to technology. I mean, I bought a Wii U, for goodness’ sake! And, in a broader sense, it can be difficult for any of us to imagine a world that’s radically different from the one we currently inhabit. My grandfather could vividly recall rushing outside to catch a rare glimpse of a motor car when he was a child, yet by the time he was in his fifties there’d been atomic weapons and humans landing on the moon. The pace of technological change in the first half of the twentieth century was unprecedented, and the lives of people were completely changed.

In my lifetime, too, I’ve seen the birth of the world wide web, the rise of portable electronic devices, and more. When I was a kid, my household had one television set, no video recorder, no computer, and a single landline telephone. By the time I moved out and got my first student flat, we had computers, games consoles, mobile phones, and dial-up internet. Then came broadband, MP3s, streaming, and smartphone apps. When I had my first weekend job I’d get paid in cash, and my first full-time job still paid me by cheque. I’d regularly have to go to the bank to pay those in – but I can’t remember the last time I set foot in a bank. I do all my banking these days on a smartphone app.

I guess this boils down to one massive question: are we anywhere near the limitations of modern A.I. systems? Or, to think about it another way, are today’s A.I. models, with all of their generative capabilities and human-mimicking interactions, genuinely capable of taking the next big leap?

A.I. models appear, to me, to be closer to parrots and mynah birds than actual sentient people. They’re quite capable of replicating “language,” on the very simple basis of “input X requires response Y,” but they don’t understand what they’re saying. That’s why A.I. systems make so many incredibly basic mistakes, and why some enquiries or conversation attempts go completely off the rails. A.I. models, in their current form, also seem to struggle with retaining information, even if all we’re talking about are a few lines of text.

Let me give you an example. While researching for this article, I “spoke” with several A.I. chat bots. And it was an interesting experience! A.I. can do some things incredibly well – it can write you functional computer code, answer questions about everything from history to mathematics, and even write an article or a story that flows naturally and is coherent. But A.I. struggles with some pretty basic things, too, like remembering what’s already been said. In just a short span of time, and without me deliberately trying to trick it, I found the A.I. that I was “speaking” with was giving totally contradictory responses to things it had said just a few minutes earlier. I could scroll up and see the older messages, but the A.I. seemed to not have that ability. It’s programmed to respond to immediate inputs – so if you ask it the same question twice, five minutes apart, you might very well get two different answers. Not differently worded answers – totally different, contradictory responses.

There’s a massive gulf between technology that’s “almost ready” and technology that actually works. Self-driving vehicles might work perfectly… 98% of the time. But that last 2%? That’s what’s stopping self-driving vehicles from going mainstream. The same with some of Elon Musk’s rockets – they’re 99% perfect… but that 1% error causes explosions on the launchpad. A.I. can do some things very well in a limited use case, and can appear to be very human with its mimicry of language. But is it really just a few years – or even a few months – away from the technological revolution predicted by A.I. 2027?

There’s not just a difference, but a massive, ocean-spanning gulf between a machine that can mimic human language and one that can operate independently. The first is like a parrot imitating its owner, incapable of genuinely understanding anything it says, and is still fundamentally operating on a “input X yields response Y” basis, with very limited ability to retain information within a single “conversation.” An A.I. system that can solve world hunger, operate entire governments, and threaten our extinction feels… well, it still seems like it’s the stuff of sci-fi. And yes, I accept that this was a very limited experiment using free A.I. bots, and that the cutting-edge stuff being worked on behind the scenes is going to be much more capable. But are its capabilities that much greater, and is this technology really the disruptive, revolutionary, and potentially world-ending threat that the authors of A.I. 2027 believe?

Generative A.I. is proving disruptive, and despite what some folks might want to think, the technology is clearly here to stay – at least in some form. On the business side of things, if an A.I. can do the work of an office full of people, well, that office is going to be closed and those folks will be laid off. I’ve also looked ahead to the future of A.I.-generated entertainment, making a bold prediction that A.I. might, one day soon, be able to generate tailor-made films and TV shows, potentially shutting down entire studios and laying off actors, writers, and everyone else.

For a lot of white collar, middle-class, creative, and upper-income-bracket folks… they’ve long considered themselves safe from this kind of automation-driven unemployment. So the arrival of generative A.I. systems that are competent and genuinely compete for those roles? That’s been a massive shock, and I think that’s why we see so many people pushing back against A.I. today in a way that they didn’t push back against all kinds of other disruptive technologies. Because, at the end of the day, most technological changes prove to be disruptive to someone. It’s just this time it’s the turn of online content creators, wealthier folks, and people with a disproportionately large voice.

But when it comes to things like A.I. drones murdering people, A.I. systems going rogue, or A.I. super-pandemics… I’m not convinced it’s something we’re on the cusp of. Nor do I feel we’re just a few years away from a post-labour tech-driven utopia where no one has to work and we can all indulge in artistic or academic pursuits. These two scenarios feel far-fetched, to me, even as some A.I. systems expand their reach and their capabilities. I’m not convinced that we aren’t close to the ceiling of what current A.I. models are capable of, nor that the kinds of doomsday or utopian scenarios laid out in A.I. 2027 would require major advances in computing and other technologies that may not even be possible.

The world is ever-changing, and technology in particular is not a static thing. My entire lifetime, really, has seen innovation upon innovation, taking me from an analogue childhood in the ’80s and early ’90s to the tech-focused life of today. I don’t doubt that there will be more changes to come, and that there will be inventions and innovations that, right now, I can’t even conceive of – assuming I live long enough to see them! So I’m not trying to dismiss out of hand the genuine concerns folks have about artificial intelligence. But at the same time, I can’t help but feel that current models could be more limited in their abilities than the A.I. evangelists want their investors to believe.

Right now, A.I. is driving an almost unprecedented level of investment, with a handful of companies making a ton of money. But is this just the beginning of an economic boom that will rival that of the post-war years or the Industrial Revolution? Or is it a speculative bubble about to burst, as we’ve seen repeatedly in recent decades? Whether we’re talking about the dot-com bubble, subprime mortgages, or cryptocurrency crashes, there are plenty of examples of speculative bubbles that got out of hand. Is A.I. just the next one? Are the promises made by A.I. creators genuine, or just an attempt to drum up further investment? Can A.I. really do what investors are being promised?

We can’t escape the reality that all of this is tied to money. A.I. companies need documents like A.I. 2027, because this conversation feeds into the narrative their executives are weaving about the future capabilities of these systems. And the promise of an incredible return on investment is what’s keeping these – otherwise unprofitable – companies in business right now. I’m not accusing anyone of running a deliberate scam, but it’s a pretty well-established way of doing business in the tech space: over-promise, rake in the cash, and only then try to figure out how to make good on at least some of those ideas. That approach has worked for the likes of Apple. But it didn’t go quite so well for companies like Theranos.

The tl;dr is this: it benefits A.I. companies to allow this conversation about their products to do the rounds. It drums up interest and attracts investment – not because investors want to see humanity wiped out and the world end, but because they see the potential for short-term financial gains. A select few companies in the A.I. space have seen their share prices increase four-, five-, and six-fold in just a couple of years – and that’s largely due to the belief that A.I. is the wave of the future. Investors believe that whoever perfects the technology first will become the world’s first trillionaire – and they want in on that. We can’t avoid that side of the issue when discussing A.I. technologies as they exist today – and their future prospects.

A.I. is already disrupting entire industries, and we’re all going to have to learn how to use these systems in the workplace in the years ahead. There could very well be fewer entry-level white-collar jobs, fewer graduate-level jobs, and fewer office jobs in general. And the potential uses for A.I. systems on the battlefield could result in a monumental change in how future conflicts unfold. But as I see it, today’s artificial intelligence systems don’t “think.” They regurgitate information when prompted, and they’re closer in actual “intelligence” to a parrot than to a person. Artificial intelligence can do some things very well – better, faster, or more reliably than any person ever could. And that’s going to be fantastic in some use cases: diagnosing diseases earlier, writing computer programmes, or creating individualised education plans for kids with special needs. But there’s a lot that A.I. can’t do – and some of it, with the limitations of computing power, may never be possible.

And it’s those things, in my view, which would be needed to turn the LLMs of today into the super-intelligence of A.I. 2027.

So that’s all for today. I hope this was interesting – though as a total non-expert, I could be completely and utterly wrong about everything! No change there, then. I’ve linked the original A.I. 2027 paper below, and if you haven’t read it, please check it out. There are also some great summaries on YouTube, too. I know this was a change from my usual content, but A.I. has been a big deal in sci-fi – and in the Star Trek franchise in particular – for decades, and it’s a big deal right now thanks to the success of the likes of ChatGPT.

If you missed it, I have another piece in which I talk about the possibility of generative A.I. being used to create tailor-made films and TV shows in the near future: you can find it by clicking or tapping here. Thanks for reading, and I hope you found my take to be interesting. Until next time!

You can find the original A.I. 2027 paper by clicking or tapping here. (Warning: leads to an external website.)

Some images generated with A.I. (yes, on purpose!) Some stock photos courtesy of Unsplash, Pixabay, and Wikimedia Commons. This article contains the thoughts and opinions of one person only and is not intended to cause any offence.