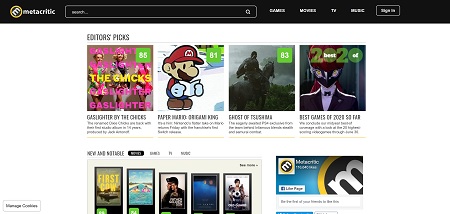

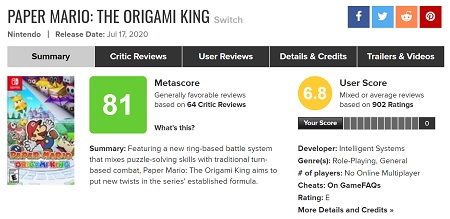

The blogosphere and YouTube have been ablaze the last 24 hours or so, following news from review website Metacritic that some titles will have user reviews blocked for a short period of time (about a day-and-a-half) after they’re released. At present this seems to apply only to video games, but I suppose it’s possible it will be rolled out elsewhere on the site. The decision has attracted a lot of criticism and some support, and I wanted to take a moment to think about the pros and cons, as well as consider some of the wider issues involved.

Metacritic describes itself as a “review aggregator”. It provides each each title with two scores – one is an average of reviews from professional critics writing for a variety of publications, and the other is from Metacritic’s own users who can write and publish reviews directly on the website. The Metascore – i.e. reviews written by professionals – is unaffected by this change. It is only the user score which has this 36-hour delay.

We should begin by considering why Metacritic has decided to make this change. In short, it seems to be designed to prevent review-bombing: the practice where users will deliberately leave overwhelmingly negative reviews as a form of protest. A number of titles across different kinds of media have been subject to this, not only on Metacritic but on sites like Rotten Tomatoes as well. The official explanation is that Metacritic wants players to have actually played a game before leaving a review, which on the surface doesn’t seem like an unfair request. But is it?

To answer that question we need to step back and think about some pretty big issues. The first one I want to tackle is the concept of censorship. Specifically, does this change mean Metacritic is trying to “censor” reviews? And if it does mean that, does Metacritic have the right to do so? These questions seem easy enough – no it isn’t censorship, and Metacritic is a private website so they can publish or not publish whatever they want within the bounds of the law. Concepts like “freedom of speech” don’t exist in this context. As someone who runs a (much smaller) website myself, I can say to you – as my reader – that you have no right to write anything here, and if you submit something to me and ask me to publish it I have the right to refuse. Am I censoring your opinion if I do so? Of course not. Finally, Metacritic has not prohibited users from writing reviews at all – this is a delay between a game’s release and the opening of the review-writing section. Reviews can still be written and published as normal after the 36 hours have elapsed.

So that seems simple – it’s not censorship. But the truth is less black-and-white. We’re in a grey area when it comes to publicly-accessible web forums, and Metacritic has made a name for itself in part because it allows users to write reviews and provide their own feedback on the latest releases. The fact that sometimes those reviews have been used in a way the site’s designers may not have originally intended isn’t a problem – it’s part of what got the site to where it is. While on a technical level this isn’t censorship and it certainly doesn’t violate any laws, many people will be looking at it as a petty, small-minded, and unfair reaction, and it has the potential to damage Metacritic’s standing in the long term.

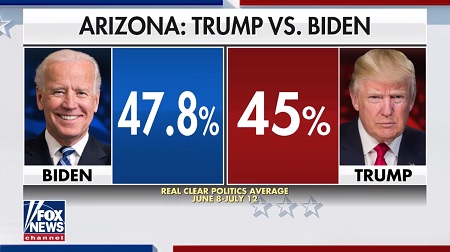

What makes Metacritic so valuable to many people is that it collates and averages out review scores. It’s like the RealClearPolitics average of opinion polls in the political sphere; one poll may be an outlier, but aggregate dozens together and you get a closer picture of what’s happening. Metacritic does the same with reviews. Reading a single review from one publication or one user may not provide a fully-rounded look at a title. Reviews vary, with different reviewers holding differing opinions on a title’s merits and faults. Metacritic presents itself as a wholly neutral space where its readers can see that rounded picture they’re often looking for. Anything that detracts from that sense of objectivity damages the site, and any opening for people to accuse it of bias and censorship undermines its entire existence, which is built on being a neutral space.

Populism is a concept in politics that has gained traction in recent years. It pits the “people” against the “elite”, and generally speaking, anyone – be they an individual or an organisation – that can successfully claim to speak for the people against the elite can be quite successful. In contrast, being accused of being elitist can be catastrophic if the accusation sticks. By seeming to prioritise the opinions of professional critics over those of amateur reviewers, Metacritic opens itself not only to accusations of bias and censorship, but also of elitism. At a politically-charged moment, where people-power is manifest in myriad forms, the one thing nobody wants to be seen as is elitist. By preventing users from writing reviews during the most crucial hours of a game’s life, Metacritic is as the very least being a gatekeeper.

Reviews from professionals, many will argue, are no less problematic than those from amateurs and Metacritic’s own users. Accusations of paid reviews abound, and while I don’t think it’s ever been successfully proven that a professional critic was flat-out bribed to write a positive review, there are certainly perks for writing positively – and there can be drawbacks for writing negatively. Several critics have spoken out about how they were pressured into writing positive reviews by threats of revoked access to future titles. Being denied a pre-release review copy of a game can be a huge problem for professionals – without access they can’t write or publish their reviews until after a game has released, at which point interest rapidly falls away. A title like, for example, Assassin’s Creed Odyssey can easily take over fifty hours to complete, meaning a post-release review could be published at the very earliest three days after the game launched – assuming the reviewer did nothing else but play and write. Even in those three days, interest drops, clicks on a website drop, and of course advertising revenue drops as a result. In short, being denied access to pre-release review copies can be very costly – and games companies know this, and are known to use it to their advantage.

There are other perks games companies can use too, such as paying for critics to attend big “events” promoting a game, where they’ll be wined and dined as well as shown off a working copy of part of the game in its best possible light. I wrote recently about such an event that I attended while working for a large games company. I’ve seen for myself the lengths some were willing to go to to market their latest titles. These events don’t come cheap, and often the objective is to provide critics with a positive impression of the company – so that when a review copy of the latest game comes around, opinions will soften. Thus we can see a “carrot-and-stick” approach: all-expenses-paid trips, freebies, and other expensive experiences offer a positive incentive to keep a company happy, while on the other hand the looming threat of revoked access (and no more freebies) actively threatens a critic’s livelihood and the profits of whatever organisation or publication they may represent. Some organisations become big enough that they may feel the latter doesn’t apply to them – but most aren’t in that category.

So when it comes to gatekeeping and elitism, Metacritic has certainly opened itself up to a whirlwind of criticism – some of which may be easier to justify than the rest. But now let’s consider a different side of the argument.

What is review-bombing? Is it justified? If so, is it justified in all cases, and is it justified even from people who haven’t played the game?

At its simplest, a review bomb is a large number of usually negative reviews (though there can be positive review bombs too) targeting a specific title. Many review bombs are started for a specific reason, and those reasons may not always be related to what’s happening in the game. Some titles are review-bombed for reasons to do with their publisher or parent company, for example. In the case of Star Wars Battlefront II, it was the game’s lootboxes and microtransactions. Review bombs are a way for people to express their dissatisfaction with a title, and as we’ve recently discussed, people’s experiences are subjective. But review bombs can draw attention to an issue with a title, and it’s up to everyone to decide for themselves whether or not that issue is a problem.

Review bombs can be used to target titles which have all sorts of perceived issues – and sometimes those issues can be story-based or even related to the politics or tone of a title. Some of the criticism of The Last of Us Part II, for example, was anti-LGBT, as that game has several LGBT characters. Other games have been criticised for political themes, and of course many titles are criticised for story failures. The film Star Wars Episode VIII: The Last Jedi was review-bombed for its storytelling decisions, for example.

This leads to the next point – what is “valid” criticism? And who gets to be the arbiter of what does and does not constitute valid criticism?

If a user’s only criticism when they write a review is that a game was “too political” or that it “forced an LGBT agenda” on players, is that okay? We’re back to questions of freedom of speech – which doesn’t apply in a legal sense, of course – as well as what Metacritic is and how it’s perceived. If Metacritic wants to remain a neutral space where everyone can express their opinions on entertainment titles – no matter what those opinions may be – then it has to accept not only review bombing, but also single-issue reviews, irrelevant/off-topic reviews, and everything else shy of legally-defined hate speech. Failing to do so will result in accusations of bias and censorship, which is exactly what we’re seeing in light of this decision. On a personal level I don’t agree with criticising a title for having an LGBT character, nor with many other reasons people have chosen to criticise titles over the years. But I’m just one person with one opinion, and in a way the whole point of the internet in general – and Metacritic specifically – has been to provide people with all kinds of opinions a space to express themselves.

Some critics have suggested that in some cases, users participating in review bombs haven’t even played the game in question, and are simply piling on. They say that this undermines the site’s user score and makes it problematic. To that my answer is: “so?” Metacritic invited users to review the latest titles. There have never been qualifications or criteria imposed on those reviews – and that means sometimes people will review something they don’t know a lot about. That’s people for ya… this is the internet, after all. The problem is that there’s no real way to prevent that – either people are free to write a review or they aren’t. And when Metacritic has for years shown itself off as a public space where anyone can submit a review, revoking that right, even for a short time, undermines the entire concept.

On a much bigger scale, Facebook and Twitter have taken a lot of flak over the last few years for their stances on “fake news”. Both sites claim to be spaces where people can gather together to discuss anything and everything, and both have become important for politicians too, many of whom now campaign using social media (especially during the coronavirus pandemic). But both sites have had issues as a result, with politicians of all stripes calling them out for “fake news” and “censorship” depending on whether a decision went in their favour or against them. And it comes down to a deceptively simple question – with huge websites like this that have a lot of power to shape opinion, who gets to be the judge of what opinions are allowed and prohibited? Metacritic, and the entertainment-based issues we’re dealing with along with it, may not be as life-changing as some of the political decisions taken by Twitter and Facebook, but it’s all in the same wheelhouse. Perhaps we’ve just traded one group of censors for another.

Metacritic has to decide what it wants to be. Is it a public forum where anyone can review the latest titles? Is it an aggregator of critical opinion – and if so, is that exclusively professionals’ opinions? Or is Metacritic itself going to step into the discussion and decide who can review a title, and perhaps even what their review can and cannot say? This isn’t the site’s first rodeo. In the past they’ve been accused of deleting negative reviews during review-bombing campaigns, and that alone means that they’re not wholly neutral. By opting to further restrict user reviews, particularly in a game’s most important hours on sale and during which many purchase decisions are made, Metacritic is inflating the value of professional opinions and removing what has been for many people an important factor in researching a game and deciding whether or not to make a purchase. Time will tell if the decision is met with a sigh and a shrug, or whether it will have lasting consequences for the website.

I don’t think it’s fair to accuse Metacritic of “censoring” opinion. Because this decision applies to positive as well as negative reviews, that case is impossible to make. But what it will do is make professionals’ voices louder, as in the absence of amateur opinions theirs will be the only ones available. To me, that seems anti-consumer. While it’s true that some reviews can be off-topic, with players taking out their frustrations on a game for reasons I may not agree with, review bombs are a legitimate form of protest, and one of the few ways people can band together to express their opinions. Occasionally they may even prompt a response from game publishers and developers, as we saw in the case of Battlefront II in 2018. Review-bombing wasn’t the only tactic used by irate gamers, but it was a factor. If we’d only been left with critic reviews at that time, we wouldn’t have known the extent of the game’s microtransaction and lootbox issues – in that sense, the torrent of negative reviews saved many people from buying a game they would not have enjoyed, and contributed to a wider backlash that ultimately forced Electronic Arts to scale back the in-game monetisation. The scale of that backlash may even lead to legislative reform to tackle in-game gambling – an issue I covered recently.

Metacritic has built a reputation as a neutral space that collates opinion rather than steps in to provide its own. Many people find that valuable – far more so than the opinions of a lone reviewer or one publication. It isn’t wholly unique, as there are other websites which aim to do something similar, but as one of the largest such sites on the web, many people rely on Metacritic for an unvarnished opinion of the latest titles. Taking steps away from that may seem justified, but in the long run will only undermine the site’s unique selling point. If too many people become dissatisfied and decamp to another site that offers what Metacritic used to, the site will disappear like MySpace did as Facebook rose to prominence. In fact, Metacritic would do well to learn from failed websites like MySpace – the lesson is that in the digital world, things can happen quickly. A fall can be just as fast as a rise, and when you’re dependent on crowds, you better keep the crowd satisfied, because there’s a whole web full of up-and-comers and smaller sites who will poach your users if you don’t treat them properly.

From the moment Metacritic opened itself to amateur reviews, review bombs and other practices its owners may disapprove of were inevitable. They lost the opportunity to be an active participant and an arbiter of content when they positioned themselves as a neutral space offering as close to objectivity as it’s possible to get. It’s too late to change now; Metacritic can no longer insert itself into the discussion without losing the very thing that draws people to it in the first place. Sacrificing its unique selling point may solve the problem of review bombs – but it risks everything the site has tried to build in the process.

People have the right to an opinion, and to express that opinion somewhere for others to see. Metacritic doesn’t have to be that space; it’s a private company and it can do what it wants with its own slice of the worldwide web. But having appeared for a long time to be that public forum, and having made a name for itself and attracted millions of users on that basis, it will be impossible for the site to step away from that role without drowning in criticism. It’s absolutely true that not all reviews are equal or equally relevant, but it has to be up to readers to decide for themselves what they think. If a game has glowing critic reviews and negative user reviews, instead of just looking at the number out of ten, taking a few minutes to read some of those reviews on both sides of the debate will be at the very least informative. And that’s where we stand – reading reviews is just as important as writing them. By taking one group of reviews away – even for a short time – Metacritic is saying to its readers that it doesn’t trust them to form their own opinions. It feels they’re too stupid or too lazy to properly understand what’s being said. It ranks professionals’ opinions higher than everyone else’s, and will push them on its readers as much as possible. I don’t think either of those things are wise.

While the move to delay reviews may seem minor, in some ways it really isn’t. Not only does it block amateur reviewers who want to make their voices heard, it does a disservice to Metacritic’s audience – the readers who rely on the site being independent and neutral. It’s also elitist at a time when the public’s tolerance for elitism is at an all-time low. And finally, it undermines what Metacritic says it wants to be and how it positions itself as a somewhat unique offering on the web.

Is it censorship to limit reviews? No. Does that mean it’s a good idea? Definitely not.

All titles mentioned above are the copyright of their respective companies, developers, publishers, etc. This article contains the thoughts and opinions of one person only and is not intended to cause any offence.