Spoiler Warning: There are spoilers ahead for the Star Wars prequel trilogy (The Phantom Menace, Attack of the Clones, and Revenge of the Sith). In addition, spoilers are present for the sequel trilogy, including The Rise of Skywalker, and for Knights of the Old Republic.

Happy Star Wars Day! In celebration of today’s event, I thought we could take a look back at the Star Wars prequel trilogy. Though this isn’t my favourite part of the franchise by any means, today is a day for positivity within the Star Wars fandom, and despite my overall feelings, the prequels did get some things right. It’s easy to criticise and complain, but no film is 100% awful. Not even The Rise of Skywalker.

I became a Star Wars fan in the early ’90s, having watched the original trilogy at the prompting of a friend. It was thus a very exciting time when the prequel trilogy was announced, and even though I wasn’t particularly thrilled with the first two films in particular, Revenge of the Sith managed to churn out an adequate end to the trilogy and set up the original films.

“A surprise, to be sure, but a welcome one!”

For a decade after the prequels concluded, Star Wars was said to be complete. Six films, and that’s it. Of course we now have sequels and spin-offs, with many more in the works, and it looks like the Star Wars franchise will continue to roll on and bring in money for parent company Disney. Though no major plans are afoot to revisit the prequel era right now, the Obi-Wan Kenobi series will bring back at least two prominent characters from the trilogy and serve as a continuation of sorts.

As always, this list is just my personal opinion. The prequel trilogy is going through somewhat of a renaissance in the minds of some Star Wars fans – particularly those who grew up with the films. If you adore the prequels, that’s okay. We all have preferences; things we like and dislike, even within a single fandom. There’s no need for discussions about Star Wars to descend into arguments!

With that out of the way, let’s jump into my list of things the prequels got right.

Number 1: Showing the Jedi Order at full strength.

At the time The Phantom Menace premiered, Star Wars’ cinematic canon had only ever shown five Force users – only one of whom could reasonably be said to still be “a Jedi” when he appeared on screen. Though Luke Skywalker appeared to take on the mantle of Jedi Master by the end of Return of the Jedi, we were still curious to see how the Order appeared in its original form.

All three films spent a decent amount of time with the Jedi Order, showing the organisation if not at its peak then certainly in far better shape than we’d ever seen it before. The Jedi maintained a huge temple as their headquarters and base of operations, and hundreds of Jedi Knights and Jedi Masters were seen on screen, taking on various roles across the three films.

Prior to this, all we really had to go on was hearsay. Ben Kenobi and Yoda had told Luke Skywalker a little about the former Jedi Order across the original films, but there’s a big difference between hearing a character explain something and actually seeing it firsthand. The legend of the Jedi Order made it to screen in a big way, and told us a lot about the history of the Star Wars galaxy as well.

We also got to know several key members of the Jedi Order in this era, and see the Jedi take on leadership roles to try to bring about peace and stave off the separatists. We arguably learned more about the minutiae of the Jedi in the prequel trilogy than in the originals, sequels, and spin-offs combined, and while it wasn’t all perfect – the Jedi robes being just one example of that – the prequels undeniably expanded the lore of Star Wars in this regard.

Number 2: Starship designs.

Many of the starship designs used during the prequel trilogy were cleverly designed with the original trilogy in mind. It’s not an easy task to take an existing design and try to work backwards from it, creating a new design that’s supposed to look like a realistic predecessor to something that was supposedly built later. But the prequel trilogy does a creditable job in this regard, especially insofar as starships are concerned.

There were two issues that the prequels faced: on the production side, technology had changed a lot regarding how special effects were made, meaning some of the original films’ starships looked very much “of their time.” And secondly, the Imperial ships seen in the original trilogy were designed to look villainous and menacing as the Empire was the antagonist faction in those films. Thus the designers had to create something that looked like a reasonable precursor to the Empire without looking too “evil” and also without looking like it came straight from the 1970s!

This is a design challenge unlike many others in cinema, and the prequels got it largely right. The Republic’s ships, both large capital ships and smaller starfighters, retained enough design elements from the original trilogy to look like plausible ancestors of things like TIE Fighters and Star Destroyers, but the brighter colours and softened edges made them look at least a little friendlier.

In any fantasy film, things like design and aesthetic world-building are easy to overlook, but they’re absolutely essential to the sense of immersion that viewers need. The best films work hard to ensure their designs are iconic, and while perhaps very few things in the prequels are as iconic as designs from the original trilogy, the designs blend together well. Nothing was outright copied, and nothing was overwritten.

Number 3: The musical score.

John Williams, who had composed and conducted the music for the original trilogy, returned to Star Wars for the prequels, and his music has to be considered one of the high points of all three films by anyone’s standards. Pieces like Duel of the Fates have become iconic and emblematic of the whole franchise, and it’s impossible to imagine Star Wars without Williams’ compositions.

Considering the budget and creative freedom George Lucas had when making the prequels, he could’ve chosen to approach any composer to create the film’s score. He didn’t have to go back to John Williams if he felt he wanted someone else, but he did. And the films are undeniably better for the inclusion of Williams’ compositions.

Number 4: Palpatine’s scheming.

Though I have argued that seeing the rise and fall of Anakin Skywalker was ultimately unnecessary to explain anything from the original films, one thing that absolutely was interesting was seeing how Palpatine schemed and manipulated events to allow himself to rise to the position of Supreme Chancellor – and ultimately Emperor.

I’m having a hard time, in light of The Rise of Skywalker, truly appreciating this aspect of the prequels, because Palpatine’s clumsy insertion into that film has done a heck of a lot to detract from his characterisation. But if we set that aside as best we can for a moment, one of the prequel trilogy’s themes – and best-executed narrative elements – was Palpatine’s rise. Though he was treated as a secondary character when compared to the likes of Anakin and Obi-Wan, I would suggest that his story was actually handled better than almost everyone else’s.

Say what you will about George Lucas and his storytelling, but when it came to Palpatine in the prequels, there was a meticulous and detailed plan from day one – and it actually made sense. Taking inspiration from the rise of Julius Caesar, who transformed Rome from a Republic into a dictatorial Empire, Palpatine’s scheme was cleverly written, with just enough shown on screen to leave an air of mystery – that the character knew more than he was letting on.

Considering that the prequels overall, and The Phantom Menace in particular, had a kid-friendly tone and plenty of action going on, this kind of political manipulation is a very adult theme, and in other films or series, the juxtaposition of politicking and scheming with space wizards and magic would have fallen completely flat. It succeeded here, in part due to being set up well and planned from the beginning, and in part thanks to Ian McDiarmid’s stellar performance.

Number 5: The Knights of the Old Republic games.

This one is a bit of a cheat since the games were not related to the films, but they were released around the same time (2003-04) and made use of a number of aesthetic elements and settings that had been established in The Phantom Menace and Attack of the Clones. I’ve said before on a number of occasions that the Knights of the Old Republic games aren’t just among my favourite video games, they’re two of the best stories ever told in the Star Wars universe.

Though distinct from the prequels, it’s hard to imagine either game being made were it not for the renewed interest in Star Wars that the prequel films generated. The use of things like Jedi robes and a Jedi Council were borrowed from the prequel trilogy as well, and Knights of the Old Republic leaned into the notion of the Jedi Order remaining a constant part of the galaxy, barely changing over millennia. This was a big part of the mythos of Star Wars at the time – the idea that the Republic had existed for thousands of years until the Empire overtook it.

The big twist in the first Knights of the Old Republic was one of the few moments where I was genuinely blown away by a storyline in a video game, and I remember sitting there with the control pad in my hands just in shock! It was a fantastically-executed narrative point, and while it isn’t really taken from the prequels, it mirrors in some respects the idea of Anakin Skywalker being a Jedi, then falling to the dark side, before ultimately being redeemed – which was, of course, a major theme in the prequel trilogy.

A third Knights of the Old Republic title was rumoured to be in production earlier in the year, so perhaps we’ll finally get a sequel! Even if that isn’t the case, or turns out to be unconnected to the original duology, they’re two of the best games I’ve ever played.

Number 6: Better lightsaber fights.

The original trilogy had a couple of solid lightsaber duels, both between Luke and Darth Vader. But the prequel trilogy in general has more exciting lightsaber combat. Not only the duels between Sith and Jedi, but also seeing Jedi in combat against non-Jedi opponents was generally done better – in my subjective opinion, at least – in the prequel films.

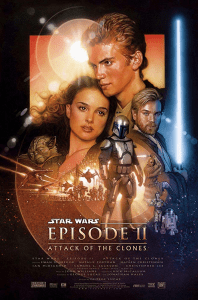

In terms of specific lightsaber duels, I’d point to the fight between Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan against Darth Maul in The Phantom Menace, and Obi-Wan, Anakin, and Yoda duelling Count Dooku in Attack of the Clones as two of the better ones put to screen in the franchise.

The prequels changed the way we imagine lightsaber combat, expanding the idea of duelling to encompass different styles and “forms” of wielding the weapon. This has been picked up in video games, films, and television shows produced in the wake of the prequel trilogy, and has gone on to be a defining part of the way lightsaber combat looks on screen.

We also got to see different designs of lightsaber hilt, and a new purple colour for Mace Windu. All of these things made a difference to the way the franchise as a whole handles its signature weapon, and a good deal of what we know about lightsabers and lightsaber duelling comes from the prequel trilogy.

Number 7: Solid acting performances.

One area of criticism of the prequel films that I fundamentally do not agree with is that the acting performances were somehow stilted or poor quality. Practically every actor involved did the best with the material they had, and some of the harshest criticism levelled at people like Hayden Christensen (Anakin Skywalker) or Ahmed Best (Jar Jar Binks) should really be aimed at George Lucas for his writing and direction.

Not only would I say that much of the criticism of the acting is unfair and overly harsh on the performers, but there are some genuinely outstanding performances in the prequel films. Ian McDiarmid’s performance as Palpatine, as we noted above, is stellar, but I’d also point to Ewan McGregor’s stint as Obi-Wan Kenobi, in particular the incredibly pained emotional moments he shares with Anakin on Mustafar.

Number 8: A planned story.

This is one which has come into sharper focus given the complete lack of overall direction afforded to the sequel trilogy. As I’ve said before, the sequel trilogy having its own narrative issues does not magically make the prequels any better, but it is worth acknowledging that the prequels had a planned story from the beginning.

Not only that, but the prequel trilogy does a creditable job of executing that story in an understandable manner. There aren’t many moments where viewers are left thinking “who’s that character?” or “what’s going on?” The narrative runs as smoothly as possible from point to point, and main characters like Anakin, Palpatine, and Obi-Wan had their arcs pre-planned.

Partly, it has to be said, this is because the films are prequels – they have a definite end point that they absolutely must reach. But there were many different ways to tell the rise and fall of Anakin Skywalker, Palpatine’s ascent to the Imperial throne, and so on. There is no denying that Lucas and others planned the story, knew where they wanted it to go, and put that to screen about as well as possible.

Whatever you may think of the story itself, this is the way filmmaking – and any storytelling, come to that – is supposed to work. If you’re going to create a trilogy of films with a view to focusing on the adventures of a few characters, planning out where the narrative and character arcs are going to go is essential.

Number 9: Tense and exciting action sequences.

Though not every action set piece worked perfectly, the Star Wars prequels do have several exciting and tense sequences. The starship crash-landing early in Revenge of the Sith is a great example of a sequence that didn’t drag on too long and kept the excitement going practically the whole time.

Parts of the Battle of Geonosis in Attack of the Clones – though a CGI mess at points – managed to be stirring and exciting too, with the last-minute arrival of a Jedi “Strike Team” to save Anakin, Obi-Wan, and Padmé achieving at least some of the feelings it was going for. Star Wars can do battles and action very well, and the prequels have some sequences that demonstrate that.

Number 10: Reinvigorated Star Wars for a new generation of fans.

I’m not surprised to see many Star Wars fans in their teens and twenties defending the prequels with such vigour. These films are theirs – perhaps the first Star Wars films they ever saw, and they’re films which, for many younger fans, started a lifelong love of a galaxy far, far away. Without the prequel trilogy, it’s likely Star Wars would be nowhere near as big as it is today. It would be a well-remembered trilogy of films from the late ’70s with a bunch of spin-off fan-fiction.

The prequels proved that there was more to Star Wars than just the original films, even though they relied heavily on those films in large part. From a business point of view, all three films were massively profitable, with the films themselves and, crucially, their merchandise bringing in literally billions of dollars. The Walt Disney Company would never have been interested in Star Wars and Lucasfilm had the prequels not demonstrated beyond any doubt that the Star Wars franchise could be more than its original trilogy.

Whatever you may think of the films Disney has made over the last few years, there’s more to come from Star Wars. I personally loved Rogue One, and I’m interested to see what some of the upcoming television series have to offer. Without the prequels, we’d never have seen Rogue One, the sequel trilogy, or The Mandalorian – or at least, they’d have taken a very different form.

Any successful franchise builds on the accomplishments of its earlier iterations, and we can see attempts for Star Wars to do so too. Those attempts aren’t always successful, but the legacy of the prequel trilogy is that Star Wars still exists and is expanding to become bigger than anyone expected it could be twenty years ago. The success of current and future projects is, to a greater or lesser extent, built on what the prequel trilogy achieved. Though I may not be wild about these three films on their own merits, the prequels’ biggest achievement may be in rejuvenating Star Wars for a new generation of fans, pushing the franchise forward.

So that’s it.

I wanted to try something positive for Star Wars to mark today, and I thought revisiting the prequel trilogy would be a good place to start.

Star Wars is in a strange place right now, in some ways. The sequel trilogy has wrapped up, but it ended in a pretty ambiguous way, and we’re still not sure exactly what will happen to the galaxy after the “final” defeat of Palpatine. Disney has shifted its focus back to the original trilogy era with most of its upcoming projects, and depending on the success of shows like Obi-Wan Kenobi, perhaps a more serious attempt will be made soon to revisit the prequel era. Time will tell!

Regardless, having watched The Phantom Menace a few days ago I thought I’d also go back and re-watch Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith to complete the set, and that led to this article in celebration of Star Wars day. It’s possible that Disney (or other companies affiliated with Star Wars, like EA) might use today to make announcements of upcoming projects, so if there’s significant news I hope you’ll check back as I daresay I’ll try to break it down.

Now, where’s my review of The Mandalorian Season 2? It’s been six months… better get cracking on that!

The Star Wars franchise – including The Phantom Menace, Attack of the Clones, Revenge of the Sith, and all other titles mentioned above – is the copyright of The Walt Disney Company and Lucasfilm. The prequel trilogy can be streamed now on Disney+ and is also available on DVD and Blu-ray. This article contains the thoughts and opinions of one person only and is not intended to cause any offence.