Spoiler Warning: Beware spoilers for the Star Wars prequels.

I’m not a prequels fan. I wasn’t when they came out and I’m not today. For all of the missteps made since Disney acquired Star Wars, the films that have been made since 2015 are superior in practically every way to the prequels. So if you’re here expecting me to say that the prequels were great, you’ve come to the wrong place.

Nor am I going to say that the sequel trilogy having problems – and it undeniably does – somehow makes the prequels better. That’s probably one of the more idiotic arguments people have put forward – “this is bad, therefore this thing that’s also bad is now good!” It doesn’t work that way.

Of course films are subjective – a film that works for one person doesn’t work for another, and that’s okay. We don’t all enjoy the same things and that’s fine. I’m not for a moment trying to argue that the prequel trilogy is objectively bad, just that it failed to win me over. In my subjective opinion. One of the biggest annoyances in the aftermath of The Last Jedi was the insistence by some fans that it was an “objectively” bad film. It wasn’t; they just didn’t like it. And that feeling is the same for me with the prequels.

Nostalgia is a funny concept, and one that can be difficult for all of us, let alone big companies, to come to terms with. If someone (like myself) watched the original Star Wars films years before the prequel trilogy was even conceived, there’s a higher than average chance they’d be disappointed in the prequels when they came out. If someone’s first encounter with the Star Wars universe was the prequels, or they were very young when they first saw those films, chances are they enjoyed them much more. Particularly as kids, a lot of the finer points of cinematography and filmmaking go completely over our heads. That’s why a film like The Emoji Movie found an audience – it’s made for kids. And those kids who saw it and loved it at age six or eight will grow up regarding it as a piece of their childhood.

In that sense, we tend to put childhood memories on a pedestal. It’s just a natural way that human beings are, and it means that some legitimately bad stories we encountered before the age of, say, twelve or thirteen are forever cemented in our brains as a positive experience. This applies to films, books, television series, and even songs, and it’s related to the idea that we’re all defined to an extent by the era we grew up in and the trends that were evident at that time. There are many examples from my own childhood; silly little cartoon shows of the 1980s which I remember with incredible fondness. British children’s television shows in that era were – when looking at them with a critical eye – awful. Animation for cartoons was dire, with whole scenes often comprised of a single static image. Stories were simplistic, there was often only a single voice actor who would make no effort to differentiate characters, but because these are some of my earliest memories of watching television I hold such programmes as Mr Benn or The Adventures of Rupert Bear in high regard. Not for their actual value, but for what they represent to me as an individual. Their flaws, while I can spot them with a critical eye, melt away. And all that remains is the positive nostalgic feelings.

For many people, the same is true of the Star Wars prequels. They were young enough when first viewing them that the flaws in the films don’t register – only the positive feelings do. And when it comes to looking back and being objective, they’re incapable of doing so. Particularly in the wake of the disappointment many fans felt at the sequels – The Last Jedi in particular – they’re clamouring for more films like the prequels, and for the figurehead of their hate, Lucasfilm president Kathleen Kennedy, to be replaced by Star Wars creator George Lucas.

But Lucas wasn’t a particularly good director or writer, especially when given the kind of leeway he got when making the prequels. His status as a legend in both the franchise and wider filmmaking industry scored him essentially free reign to do whatever he wanted when he started to make the prequel trilogy. This wasn’t the case when making the originals, and a group of incredibly talented creative people, including John Williams the composer, as well as editors, directors, script doctors, and so on all contributed massively to those films’ success. Lucas may have come up with this kernel of an idea, but to say he alone was responsible for Star Wars as we know it simply isn’t true. And when given free reign to tell his own story in the universe, he came up with a series of three films which undermined Star Wars’ classic villain, Darth Vader.

When we encountered Vader in 1977’s Star Wars (later retitled Episode IV: A New Hope) we knew all we needed to know. He was “more machine now than man”, he had a very powerful command of the Force, and he was ruthless. Seeing nine-year-old Ani, and trying to frame at least the first two films of the prequel trilogy to make him the protagonist detracted from that, in practically the same way as Hannibal Rising detracts from the character of Hannibal Lecter, or the 2005 remake of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory overexplains Willy Wonka. Some characters work because they’re mysterious. We didn’t need to know that Willy Wonka runs a sweets factory because his dad was a miserly old dentist. And we didn’t need to see Hannibal Lecter as a scared orphan – it took something important away from the character. And the same applies to Darth Vader. Seeing him as a bright-eyed child, with much of the film shot to make him as sympathetic as possible, robs Darth Vader of much of his imposing fear factor.

To explain why, let’s hop from one franchise to another and look at Star Trek: The Next Generation, and in particular the two-part episode Chain of Command. Capt. Picard has been captured by the Cardassians, who are trying to get him to reveal sensitive tactical information – using torture. It’s one of TNG‘s finest stories, but one moment in it is interesting, and it shows why too much backstory ruins a threat. At one point, days or weeks into his captivity, Picard is sat down with his torturer, Gul Madred (played expertly by David Warner). Madred tells Picard a little of his life growing up alone and in poverty on Cardassia, and Picard seizes upon it, proclaiming: “Whenever I look at you now, I won’t see a powerful Cardassian warrior. I will see a six-year-old boy who is powerless to protect himself. In spite of all you have done to me, I find you a pitiable man.” The circumstances are not the same – we’re the audience looking in, Picard is a character in the middle of it. But the effect is the same. Too much information detracts from a villain.

The creative decision to allow us, the audience, to see Darth Vader as a child, to tell his story as a young man, robs the character of a significant part of his imposing nature. He could still tear us apart with his lightsaber or choke us to death while not even being on the same starship, but all the while we’re still able to pity him, not be afraid of him. Lucas allowed the most significant element of his story’s most important character to be lost through this decision. Instead of wondering what horrors lay beneath the mask, or what twisted reasons Vader had for giving himself mechanical parts, we now know not only that he was a slave, that he grew up in poverty and cried for his mommy, but that underneath that scary suit is a burnt-out husk, and without the suit he’ll just suffocate and die. As he ultimately does.

The reveal of Vader in Return of the Jedi as a mere man, a fragile, badly wounded man kept alive by this suit we’d come to fear over three films, is robbed of all dramatic effect too. In Return of the Jedi, this powerful scene is rendered almost meaningless, because we’ve already seen what he looks like under there in Revenge of the Sith – which showed us more than we needed to see of his injuries. Vader’s transformation from imposing and frightening villain, redeemed through his one good deed, is complete. It began with seeing him as a child, it ran through his stint as protagonist, and finally seeing the painful, life-limiting injuries he had to live with, as well as the mental anguish he went through after the loss of his wife, change fundamentally how we see him. And it’s not a change for the better. Sometimes, less is more. The original film gave us everything we needed to know about Vader. The prequels told us too much.

While for me, the fact that the prequels seriously undermine Vader as a redeemable villain is their most unforgivable error, the prequel trilogy also throws up a huge number of other issues, some minor and some more major. Many of these are present simply as a result of the nature of prequel stories, and others are just a consequence of bad and/or lazy writing.

One of the biggest criticisms I’d have of the sequel trilogy is that it was split up. There wasn’t any attempt made to tell one single story over three films, instead the writing was split up between different writers and directors, with each given free rein to tell whatever story they wanted. The result is a jarring tonal mess. The prequels don’t have that issue, because generally George Lucas knew what story he wanted to tell. There were tweaks, certainly – Jar Jar Binks’ role was scaled back after the response to The Phantom Menace, for example. But overall, he knew what story he wanted to tell and he made three films to tell it. Problem is, the story was crap.

Politics can be exciting, and political dramas can be thrilling. At a fundamental level, the rise of Palpatine from being a senator from a backwater planet to Supreme Chancellor and then Emperor is the same as the rise of the scheming Frank Underwood in House of Cards – and watching how he manipulated circumstances to become Vice President and then President was both fascinating and exciting. So I disagree with those who say that all of the politics behind Palpatine’s rise is a fundamental flaw; if handled differently it could’ve been okay – though it’s not necessarily what fans wanted or expected from a Star Wars film.

The prequels didn’t fall flat for any one reason, though Vader’s characterisation is a significant issue all by itself. There were dozens of smaller problems that they created. Jar Jar Binks is mentioned frequently by detractors of the films, though he was really only a significant stumbling block in The Phantom Menace, being largely absent from the two other titles in the series. It’s understandable to see why he was disliked though: in a film that a lot of people had been waiting almost twenty years to see, there was this oafish character with a hammy performance that seemed to be aimed at children under five. Many of those kids, by the way, are the prequel films’ defenders today as mentioned above. Reaction to Jar Jar was so extreme that some fans even went so far as to edit him out of the film, cutting his scenes entirely in a reworked fan-edit of The Phantom Menace. But Jar Jar was there to give the film extra appeal to children, because Star Wars has always been – despite what many hard-core fans want to think – a family franchise. I wouldn’t go so far as to say they’re kids’ films, but they’re films which have always appealed to children and though there’s nothing wrong with adults enjoying them too, Star Wars wants to keep that child-friendly atmosphere. After all, it’s mostly kids who buy toys and other merchandise.

And that’s another big point. The original films had made a lot of money from merchandise, so when the prequels rolled around the expectation was that they’d do the same. Some creative decisions can be linked to this, such as the decision to have “Jedi robes” mimic Alec Guiness’ costume from the original film. That costume was clearly something fit for wearing in a desert environment, and wasn’t originally supposed to represent the robes of the lost Jedi order. If it was, why would Obi-Wan be so blasé about wearing it everywhere he went? If the Jedi are being actively hunted, any surviving Jedi would be taking steps to ensure no one knew of his or her identity. The fact that this doesn’t happen is an example of a prequel-created plot hole.

By going back in time to before the original films, the Star Wars prequels create a number of inconsistencies and issues for the franchise. This isn’t something unique to the prequels – the reveal that Darth Vader is Luke’s father in The Empire Strikes Back, and the semantic gymnastics required to get around that in Return of the Jedi (remember “from a certain point of view”?) was the first and biggest example. But the fact is that that reveal worked – it was dramatic, shocking, and for the vast majority of the audience who didn’t remember Ben Kenobi’s one line in the previous film about Luke’s dad, wasn’t in any way contradictory.

But it’s stated several times that Yoda is the Jedi who trained Obi-Wan. Yet in The Phantom Menace, we’re introduced to Obi-Wan Kenobi as a padawan apprentice – whose master is in fact Qui-Gon Jinn. Liam Neeson’s performance as Qui-Gon is one of the few high points of that film, so I’m not trying to detract from the character altogether. But it’s yet another example of the prequels taking what was already established and ignoring it. It would have been perfectly feasible to have Kenobi and Jinn as partners, teamed up in much the same way, and still establish firmly that Yoda was Obi-Wan’s master. Same story, no contradiction. One or two lines of dialogue and/or an extra scene would’ve established this and it would fit right in with canon.

Then there’s the inclusion of C-3PO and R2-D2. Obi-Wan spent a lot of time in the prequels with R2-D2 in particular, yet in A New Hope claims to have never seen the droid. That must’ve been depressing for poor R2. Not to mention that Anakin build C-3PO as a child. Okay, this one isn’t so much a plot hole as it is stupid.

Speaking of stupid – Anakin was conceived with “no father”, implying a Jesus-esque immaculate conception via the Force. This was vaguely tied into the “prophecy of the chosen one”, which is referenced several times across the three films, but ultimately serves very little purpose. Star Wars has, and continues to have, problems with the idea that people – good and bad – can come from ordinary beginnings. Anakin had to be a Force baby. Rey had to be a… well, spoiler alert for The Rise of Skywalker. Luke couldn’t just be a great Jedi, he had to be Vader’s son. And so on. Because both the immaculate conception and chosen one concepts were handled so poorly, it wasn’t even obvious that this was Lucas’ intention. The famous opera scene, where Palpatine tells Anakin the “story of Darth Plagueis the Wise” is supposed to imply that Plagueis created Anakin by “manipulating midi-cholorions to create life”. Except, we never met Plagueis, we never saw any of this happen, and no timeframe is hinted at by Palpatine in the scene. As far as I knew on watching the films, the Plagueis legend took place centuries earlier, and was just another way Palpatine could get his hook into Anakin to sway him. It was also never expressed that Palpatine was the one giving Anakin the visions of Padmé’s death – though again we’re supposed to have implied this somehow. Even though the film is shot in such a way that we don’t.

Some of these ideas actually have merit – particularly the concept that Palpatine was both giving Anakin the visions of his wife dying while at the same time hinting he knew enough about the Dark Side that he could save her. That shows Palpatine at his devious best, except it never fully made it to screen. It instead stumbled halfway onto the screen, then fell flat. And that’s a shame, because it’s one of the few good story points the prequels had.

A little while ago, I read an article where someone had suggested that the prequels would have been made significantly better if Revenge of the Sith had been all three films, and The Phantom Menace and Attack of the Clones were never made. This might actually be a decent idea, because it would have allowed some of the themes and concepts in Revenge of the Sith more screen time to be properly explored, instead of merely mentioned in passing or hinted at.

So those are some of the story threads that failed in the prequels. And by far, story and characterisation is where the prequels failed hardest for me. But on the production and filmmaking side, there are major issues too.

The late 1990s and early 2000s were when CGI was really becoming a big deal in filmmaking. But the CGI in those days was pretty rough, meaning a lot of films produced in that era that rely heavily on those kind of effects have aged very poorly – and didn’t even look great at the time.

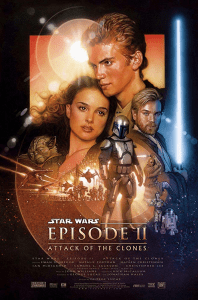

This is arguably at its worst in Attack of the Clones, where legions of clone troopers are seen, rendered in CGI. And it looks like a mid-2000s video game. The CGI is unrealistic, far too “shiny”, and not at all lifelike. The fact that these films were largely shot on green screens with few practical effects has dated them horribly, and the aesthetic they present is poor by anyone’s standards. CGI today is still an impefect medium, but back then it was far worse.

Where the original films have a late-70s, early-80s aesthetic, complimented by some wonderful puppets and practical effects giving them a unique charm, the prequels just look like a low-budget fan film of the kind you’d find on YouTube by comparison. Even in The Last Jedi a little over two years ago, director Rian Johnson opted to use a puppet to represent the spirit of Yoda, believing CGI would look worse. And he was right – CGI would’ve looked worse that a physical puppet. In 2017. So you can imagine how much worse it would’ve looked in 2002 – but you don’t have to, just take a look at Yoda in Attack of the Clones.

One thing that the visuals of the prequels did get right, and I’m happy to give credit where it’s due, is in how the Republic ships, troops, and overall aesthetic is clearly linked to the later Imperial aesthetic that we know from the originals. The Republic had its own look, but it was clearly a predecessor to how Imperial things looked, and the attention to detail to get that right is impressive.

And there were some decent performances from the cast. All of the main cast, really. Part of the reason fans are excited for the Obi-Wan Kenobi spin-off television series is because Ewan McGregor was fantastic in that role. I’d argue he gave a great performance from three poor scripts, as did other actors like Liam Neeson, Christopher Lee, and even Hayden Christiansen, but the fact is that as acting performances they’re all decent. I don’t believe for a moment the prequels flopped on account of bad acting. Some of it was “hammy”, certainly, but that’s how the films were written.

Again, it’s worth crediting Lucasfilm in the prequel era with crafting and telling a single story. That’s absolutely how filmmaking should work, and the idea that writers/directors can “pass the baton” from one to another without even having the barest bones of a story structure to work from has meant that the sequel trilogy has not been the success it should’ve. The fact that I personally dislike the story of the prequels, and the plot issues it creates, as well as the overreliance on bad CGI, doesn’t mean I don’t appreciate that it was planned and told as one story – the fall of Anakin Skywalker.

I’d just argue that we didn’t really need to see his fall to know he’d fallen, nor to understand how he came to be redeemed in Return of the Jedi. Once it had been established that Luke was Vader’s son, his path to redemption existed and seeing how he came to be Vader rather than Anakin was an unnecessary addendum. It isn’t in any way necessary to watch the prequels, or even read a plot synopsis, to understand how anything in the original trilogy came to unfold. In fact, in many ways it detracts from that experience, particularly if someone new to the franchise were to choose to watch the prequels first. But again, that’s my opinion, and all of this is subjective.

At the end of the day, it’s easy enough to ignore or not watch the prequels and still enjoy Star Wars for what it is and what it represents. To me that’s a positive thing, because I’m not arguing that the prequels somehow “ruin” Star Wars. But it’s also a fairly damning indictment – three films telling the rise and fall of a main character are ultimately wholly unnecessary and contribute nothing to the story except exposition and background.

Star Wars was, for me, Luke’s story, not Vader’s. And overexplaining his origins, from his “virgin birth” and awkward childhood through his spell as the series’ protagonist, ultimately did more to detract from his character as an imposing but ultimately redeemable villain. By turning Vader into an object of pity, the prequels ultimate sin was in robbing Star Wars of its best villain and most mysterious Sith Lord.

The Star Wars prequel trilogy is available to stream now on Disney+, and may also be available on DVD and Blu-Ray. The Star Wars franchise – including The Phantom Menace, Attack of the Clones, and Revenge of the Sith – is the copyright of Lucasfilm and Disney. This article contains the thoughts and opinions of one person only and is not intended to cause any offence.