Spoiler Warning: Beware minor spoilers for Indika’s story – and major spoilers for the game’s world and mechanics.

I love seeking out games that feel unique – and if there’s one word I’d use to describe Indika, that would be it. This game is a mix of third-person puzzling, some platforming elements, a “walking simulator,” and some fun 2D platforming levels inspired by titles from years gone by. It’s a short but eclectic experience; a memorable game that I thoroughly enjoyed.

I beat Indika in a single play session – something I don’t think I’ve done with a game for quite a long time! So this is not an epic experience that’s going to last dozens upon dozens of hours… and that’s something to be aware of heading into it. However, unlike some recent titles, Indika is priced fairly. At £20 here in the UK (though I got it at a slight discount via the Epic Games Store) its price feels more than fair for the runtime it provides, and I will always credit publishers for recognising this!

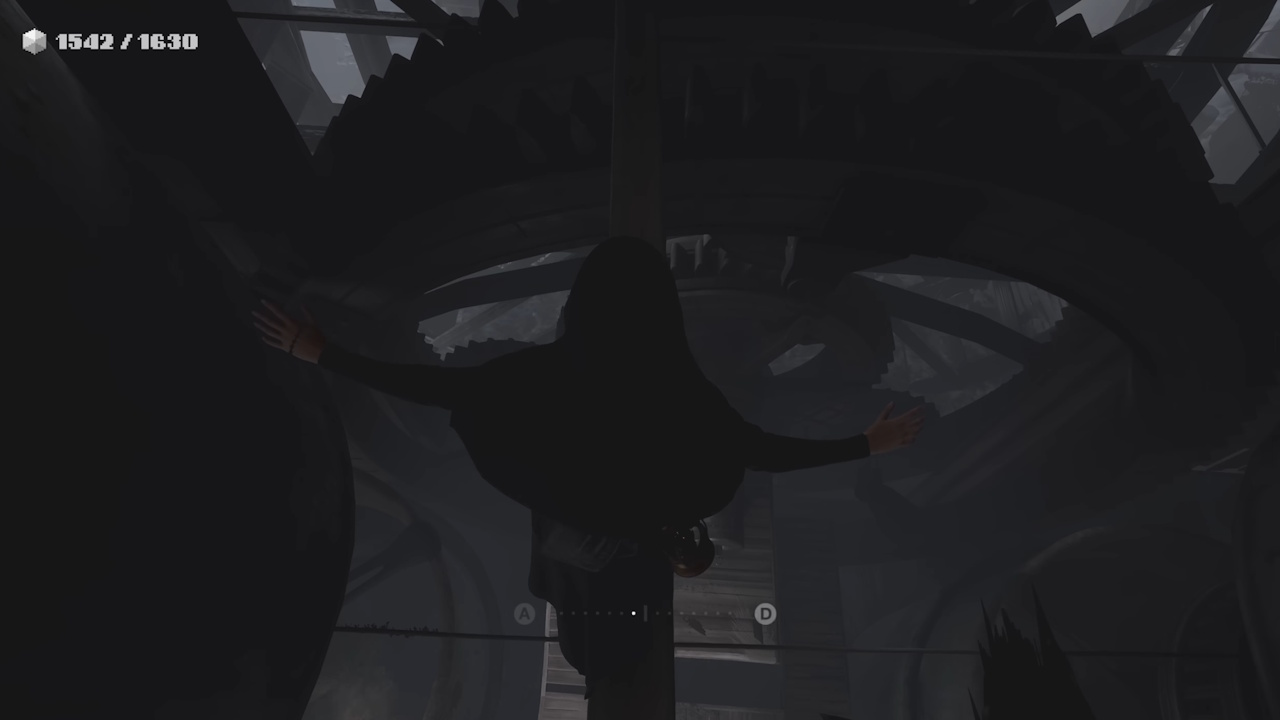

During my playthrough I did encounter a bug – just one, though. At one point, Indika got stuck in the environment partway through climbing onto a platform, and the only way around it was to restart the level. This highlighted something I don’t really appreciate: the lack of a free save system. Indika is generous with its checkpoints, sure, and the only other time I died I didn’t have to go all the way back to the beginning or anything. But… being able to freely save is a pretty basic feature, and even in a game as short as Indika there’s really no reason not to incorporate it.

But that’s basically all of the negatives out of the way!

Indika is a narrative experience as much as a “game” – there are entire sections where the only thing you’re required to do is walk from point to point. There are side-rooms to explore and a few collectables to pick up – which are worth finding, if for no other reason than to appreciate the design work that went into making them – but much of the game unfolds like this. I can see some people finding that “boring,” and while such things are subjective, for me I enjoyed this slower pace.

Despite the way the game seems to present itself at first, this isn’t a “horror” title – not by my definition, at any rate. There are some creepy and unsettling elements for sure; a game where the player character speaks to a demonic entity is gonna have that! But in terms of frightening moments or jump-scares… there really weren’t any. And that’s coming from a total scaredy-cat who’s easily frightened!

What you get with Indika’s narrative is a lot of philosophy – the age-old debate about God’s existence. And maybe you’ll say I’m projecting my own biases here, but I felt Indika came down firmly on the side of atheism. Despite being a nun, the protagonist is clearly struggling with questions of faith, and her mental illness – which is how I’d interpret her hallucinations – is preventing her from fitting in with her fellow nuns at the convent. Having encountered a runaway convict, Indika bounces her ideas about God and the problems of omnipotence and evil off of him. These conversations were genuinely interesting.

Both of the main characters – and Indika’s companion, too – felt fleshed-out, and they seemed to fit the world they inhabited. We got to see really interesting glimpses of pre-First World War Russia, a country struggling with industrialisation and the challenges that it brought. Indika’s convent felt like a place unchanged by the passage of time, but the world she stepped into was one of steam trains, factories, and industrial danger. The world could feel bleak – its wintery setting definitely adding to that tone – but never empty. I loved crunching through the snow during the outdoor sections!

There’s something about snow in video games that I just really enjoy. Seeing Indika and Ilya leave footprints was a nice touch, too. While the snow isn’t at the same level as a title like Red Dead Redemption II, it isn’t a million miles away. And considering this game was made by a much smaller team with a lower budget… I think it’s pretty fantastic the way it’s turned out. In the west, we tend to associate Russia with freezing winter conditions – even though, of course, the country has three other seasons – so in that sense, the snow also felt on theme!

One of the projects I chose when I was studying history at university was the history of colour photography. Among the earliest surviving colour photographs were taken in the late 1900s and 1910s by Sergey Prokudin-Gorskii – a Russian photographer who was commissioned by the Tsar to take colour photographs across Russia. I immersed myself in Prokudin-Gorskii’s photographs while working on my project, and I was fascinated by this glimpse into pre-Communist Russia. I know folks say black-and-white photographs feel atmospheric, but there’s something about colour that’s just so much more real!

I bring this up because I felt echoes of Prokudin-Gorskii’s photographs in Indika. The convent, some of the wooden houses and buildings, the dirt roads… I remember seeing all of those things in those photographs. The juxtaposition between massive imposing religious buildings made of stone and adorned with gold and bright colours with small, wooden houses in which everyone else lived… it’s striking. And you can see why, in years gone by, people would be drawn to churches and cathedrals. For my money, developers Odd-Meter did a great job recreating this bygone era in video game form, and it brought back memories for me of working on that university project and exploring the forgotten world depicted in those photographs.

For a game that was – mostly – an intense, philosophical narrative experience set in a realistic historical setting… Indika blended in some very “video-gamey” elements! Its pixel art font – used in menus and the levelling screen – was a real throwback, as were the way points were collected in-game. Points appear in front of Indika when collecting items in the game world or lighting candles – but they appear as big, glowing, pixellated blocks. They reminded me of something out of the 8-bit era, and that was clearly a deliberate choice. It added to the surreal nature of the game, and I think it worked exceptionally well.

Then there’s the game’s soundtrack and… well, sound-scape might be a better term. There were some beautiful and haunting melodies created for Indika, but there were also some retro throwbacks that felt like something you’d have heard on an arcade machine in the ’80s! Again, it’s the surreal blending of the game’s detailed world with these modern/retro game elements that just… worked. It shouldn’t, and I think in a worse game it wouldn’t have worked. But here, the total clash between the world around Indika and these retro gaming visuals and sounds actually felt great. If the story is partially about Indika’s mental health, I kind of read the gaming elements as part of that. Part of her hallucinations – both visual and auditory.

These tied in with some wonderful 2D platforming sections. Indika presented its flashback sequences in this retro pixel art style, which is something I found incredibly creative. It felt kind of like if a film or TV show depicted its flashbacks in black-and-white or sepia. It’s the game saying “these events happened in the past.” And what better way for a video game to depict the past than with older visual and gameplay styles?

These sections also provided a clear boundary between the present and the flashbacks, making them feel completely distinct. Although I described them as “2D platformers,” there was more to it than that. We got a Pac-Man-inspired section, running around a maze-like level, a multi-lap bike race, and two very different platforming sections. These all felt unique, with no single play style being repeated throughout the flashbacks. They were also some of the most technically challenging parts of the game – or perhaps my 2D gaming skills are just rusty! My arthritic hands don’t help, either, with sections requiring near-perfect timing of jumps! But I struggled through and got there in the end.

Depicting such intense sequences in this way was kind of an odd choice. Indika’s flashbacks tell a tale of the protagonist’s first romantic encounter – with a boy from a different culture, and it doesn’t end well. There were some light-hearted moments in these 2D levels, particularly near the beginning, but the story took a dark turn later on. And the pixel art, upbeat 8-bit music, and fun retro level design… it clashed with that. But as above, I think the clash is the point.

The 2D levels weren’t the only creative ones, though. Indika did some clever things with some of its 3D environments, too – including a series of rooms which rotated, having you walking on walls and having to move objects ways that don’t conform to the laws of physics! Some games have tried to show mental illness and fractured minds before, but there’s something so unsettling about walking into a room with absolutely no explanation, and no expectation that it’s going to be something different… only to realise it’s upside down, walking on walls… and with some kind of strange multi-limbed demon just out of sight.

Other 3D puzzles were more basic, akin to something you’d see in games like Uncharted. “Basic” is not a synonym for “bad,” and these puzzles – involving things like moving objects on a crane or using a ladder to bypass a locked door – were entertaining enough. None of them were especially difficult to solve, though I would point out that the game doesn’t hold your hand and just kind of drops you in the puzzles, leaving you to figure it out. As another hallmark of what we might call “old-school” game design – in a modern gaming landscape dominated by in-depth tutorials and the dreaded quest marker – I think I like this even more!

Then there were sections of levels that used different or interesting mechanics. Repeatedly rotating the control stick to wind a winch was interesting – and reminded me of some Nintendo 64 titles from back when the analogue stick was a brand-new invention! Then there was a moment where Indika had to balance on a narrow beam that gave me flashbacks to Shenmue II! If you remember that level… does it haunt you, too? Indika also gives you control over a couple of different vehicles, as well as some pieces of machinery, and there’s a couple of tense chase sequences, too. There’s a surprising diversity of gameplay styles on show given the game’s runtime.

I’d also be remiss not to mention Indika’s incredibly creative use of the protagonist’s hallucinations. Without giving too much away, at a couple of points in the game, Indika experiences a vivid hallucination, but can keep it at bay through prayer. Alternating between the hallucination and the “real” state of the world changes the level, and opens up different pathways to get from one end to the other. It’s a really creative mechanic that wasn’t over-used, and it worked exceptionally well.

So Indika was not the kind of game I would’ve ordinarily chosen. It’s a short experience (my playthrough clocked in at just under four-and-a-half hours, including the credits, a couple of deaths, and one 2D level that took a few attempts). But it was really interesting – a philosophical video game with a message about faith, God, and the way the world works. It was wrapped up in an interesting narrative about a renegade nun with a mental illness, and touched on how mentally ill folks can be treated and shunned by society. As someone with a mental health condition myself, I appreciated the message, the depiction, and how the game handled that side of things.

Russian developers Odd-Meter actually left the country during work on Indika due to the political situation there. But almost the whole team is Russian – there are Russian-language voice options available if you want to get more of an immersive experience.

I would absolutely recommend Indika. I had a blast with it, and I really can’t think of another game quite like it. As I said at the beginning, this was a completely unique experience, both narratively and mechanically. Maybe you think four-plus hours is “too short,” but again I would point to the game being – in my view, at least – fairly-priced for its runtime. We aren’t talking about a £75 title, here.

So I hope this has been interesting! I thought Indika had only just been released, but it actually came out over a year ago. I guess I’m a bit late to the party, but never mind! The game was on sale recently, at least on PC if you use the Epic Games Store. It could also be one to wishlist ahead of the big Christmas sales, because it might drop in price again.

This could’ve absolutely not been my cup of tea! The idea of a mentally ill protagonist with a horrifying demon whispering in their ear, a clash of visual and musical styles, the philosophical conversations, lack of combat, and short runtime… they could all be offputting, I guess. But I really liked this game. It’s the kind of title I think we can point to when highlighting the work of smaller, independent development teams, and it’s also a fine example of video games as a narrative art form.

Indika is out now for PC, PlayStation 5, and Xbox Series S/X. Indika is the copyright of Odd-Meter and/or 11 Bit Studios. This review contains the thoughts and opinions of one person only and is not intended to cause any offence.