Spoiler Warning: Beware of spoilers for the following Star Trek productions: The Original Series, The Motion Picture, The Next Generation, Voyager, First Contact, Discovery, Picard, Prodigy, Strange New Worlds, and Starfleet Academy.

2026 will mark the 60th anniversary of the Star Trek franchise. And what better way to celebrate the beginning of this milestone year than by stirring the pot in the Trekkie community? So today, I thought we could all enjoy six more of my patented Star Trek “Hot Takes!”

Before we go any further, I’d like to give a couple of caveats. Firstly, these are all opinions that I genuinely hold, and I’m not making things up for the sake of clickbait or to deliberately upset people. But, with that being said, I’m also a huge Star Trek fan, and I share these “hot takes” with tongue firmly embedded in cheek! This is meant to be a bit of light-hearted fun in the 60th anniversary year – not something to get too worked up or annoyed about.

These are *hot* takes, not “super obvious takes that everyone will agree with,” so you can expect some degree of controversy! And, as always, everything we’re talking about is just one person’s *subjective, not objective* opinion. Feel free to disagree vehemently; I’m well aware that my position will be the minority one in most cases. However, if you aren’t in the right frame of mind for some potentially controversial Star Trek opinions… consider this your final content warning!

With all of that out of the way, let’s celebrate the beginning of Star Trek’s big sixtieth anniversary year with six “hot takes”!

“Hot Take” #1:

Star Trek got way better after Gene Roddenberry was out of the picture.

Gene Roddenberry was Star Trek’s creator. He established the world, the lore, the look and feel of Star Trek… he quite literally built the franchise from nothing, and his philosophy and ideas are *still* a core part of Star Trek today. But after Roddenberry lost control of the cinematic franchise in the early ’80s, and especially after he stepped away from day-to-day work on The Next Generation, well… that’s where Star Trek got a heck of a lot better.

Gene Roddenberry cut his teeth on the TV serials of the mid ’50s, and his writing style… it never really evolved beyond that, even as the entertainment landscape around him was utterly transformed. Look at his final work with the original Star Trek crew: The Motion Picture, which he was heavily involved with, had a troubled production, with script re-writes happening during filming, and the finished story feels like an extended cut of a TOS episode. This came two years after Star Wars, a year after Superman, and the same year as Alien and Apocalypse Now. And although The Motion Picture made more than its money back, it’s not exactly the definitive Star Trek story for either Trekkies or a more general audience.

The simple truth is that Roddenberry was lapped by a new generation of sci-fi storytellers and filmmakers in the years after Star Trek. And ironically, many of those projects would never have been greenlit were it not for the huge success of Star Trek! But by the end of the ’70s at the very latest, what Gene Roddenberry was capable of, particularly as a scriptwriter, had fallen way behind audience expectations. He tried to reclaim his place at the head of the Star Trek franchise with The Next Generation in 1987, but again… most of that show’s best episodes and stories came *after* he was no longer involved.

In The Original Series, Roddenberry penned the critically-panned episode The Omega Glory, his original treatment of The Cage almost got Star Trek cancelled before it could get off the ground, and of the other writing credits he has in the franchise… could you name a single one? Return of the Archons, Bread and Circuses, The Savage Curtain… none of these leap out at me as being “must-watch classics.”

Roddenberry had a very rigid, almost dogmatic vision of what the future should look like. And, admirable as that may have been, it didn’t really lend itself to interesting, engaging, or realistic storytelling. If Starfleet characters and humans in this era are all heroic paragons of virtue, free of prejudices, conflicts, and negative feelings of any kind… how do you build tension and drama in a story? How can characters have arcs when they begin at “already perfect”? And the less we say about Roddenberry’s self-insert character of Wesley Crusher (named after his own middle name) the better!

Okay, okay. I’m exaggerating just a little. But I don’t think it’s a coincidence that The Original Series films were better-recieved after Roddenberry was kicked off them. Nor that The Next Generation began to improve after he was no longer directly involved. I personally *adore* The Motion Picture, but there’s no denying it’s not one of the best films in the franchise in most people’s opinions. Gene Roddenberry was simply a man of his time… and his time came and went. When The Next Generation was underway, and spin-offs were being worked on, Roddenberry’s time was over. And Star Trek improved as a result. Characters could be flawed, humanity and Starfleet could better reflect the world of today by being imperfect, and Star Trek began to feel less like an impossible utopia or a morality fable and more… real.

“Hot Take” #2:

The overuse of legacy characters did more harm than good in modern Star Trek.

In 2018, I was… concerned. For the second time in a decade, we were going to see Captain Pike and Spock re-cast for a new project: Discovery’s second season. And, around the same time, we also learned that Jean-Luc Picard was being brought back for his own series. Star Trek’s return to its small-screen home had already been complicated by including Michael Burnham as Spock’s long-lost adopted sibling, but these announcements seemed to signal a disturbing trend: Star Trek was doubling-down on legacy characters and storylines at the expense of trying something new.

And that trend would continue. Prodigy, despite being billed as a show for kids, functions more as a sequel to Voyager than an independent production. Picard quite literally dumped almost all of its new characters – without bothering to resolve most of their arcs and storylines – in order to bring back the crew of The Next Generation for one final adventure. And Strange New Worlds, despite introducing us to some interesting new characters, focuses excessively on Spock, Kirk, Uhura, Scotty, and other TOS characters that have been introduced. We even got an entire episode in Season 3 where it was *only* those legacy characters who were in focus.

If I’m right, and Star Trek will be disappearing from the small screen for the foreseeable future in the next few years, I really think we’ll come to regret this overabundance of legacy characters. Why? Well, to put it simply: it’s left Star Trek with nothing to build on and nowhere to go in the future. You and I may love Janeway, Seven, Picard, Riker, Spock, Uhura, and more… but these stories have either been sequels, showing these characters firmly in retirement or at the ends of their careers, or prequels, bringing the characters from their younger selves closer to the people we remember. By the time these shows are all over… where’s the foundation Star Trek needs to build something new?

There are ways to include legacy characters without totally overwhelming or swamping a production. But it requires discipline on the production side of things. It needs someone to step in and say “no, we’ve seen enough of the Doctor or Uhura or Picard already, let’s tell a story that focuses on someone new.” It’s my hope that – however late in the day it may be – Starfleet Academy will strike a better balance in this regard that any of its predecessors have. It’ll be fun to catch up with the Doctor after all this time… but he doesn’t need to be a main character. He should be, as Robert Picardo has said, “the Yoda of Star Trek,” offering advice and help to this new cadre of cadets, but without getting in their way or making things all about himself.

Look at the absolutely awful mess that Star Wars has gotten itself into thanks to an inability to move on from legacy characters (and the only story that the franchise has ever told). Is that what we want for Star Trek? If Star Trek had gone down this kind of route in the ’80s and ’90s, sticking doggedly with Kirk and his crew, think of all the incredible characters we’d never have met, and all of the stories that would’ve never been told. Modern Star Trek, by focusing so heavily on legacy characters at the expense of new creations (and, arguably, because some of the few new creations haven’t been particularly well-written or well-received), has deprived the franchise of innovation for current audiences, failed to open the doorway to new audiences, and most importantly, stagnated the franchise and left it with fewer narrative directions in the future.

I can’t help but feel, as this current streaming era seems to be winding down, that modern Star Trek will come to be seen as a catastrophically mishandled period, and a massive missed opportunity to build a new, solid foundation for the future. In another twenty or thirty years, there won’t be able to be a revival of any of the modern shows, except perhaps for Lower Decks, because of how heavily they’ve all leaned on either returning actors or re-cast characters. There’s nowhere left for most of them to go now, and they’ve left Star Trek as a whole feeling kinda… tired.

“Hot Take” #3:

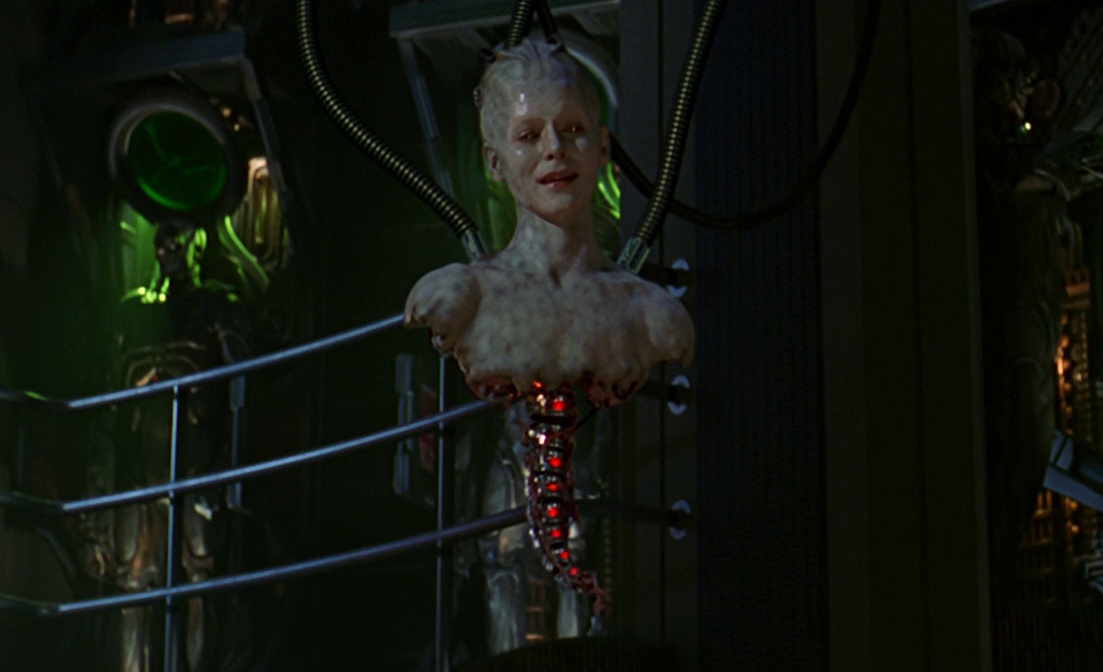

The Borg Queen ruins the Borg, and her inclusion fundamentally misunderstands the Collective and what made them such an intimidating villain.

This is a subject I’ve touched on before – and it really ought to be a longer essay on its own, one day! For now, here’s the short version: the Borg Queen has always felt, to me, like the worst and most egregious kind of studio interference. “Films need to have villains!” decreed someone at Paramount Pictures in the mid ’90s, and because the Borg had already been decided upon for First Contact, the writers had to go out of their way to create a unique individual Borg character for Picard, Data, and the others to face off against. Even though the idea of a “unique individual Borg” is a complete oxymoron.

Think back to what Q told Picard when the Borg first appeared in Q Who: “They’re not interested in political conquest, wealth, or power as you know it. They’re simply interested in your ship, its technology. They’ve identified it as something they can consume.” That description presents the Borg as an adversary for the Federation unlike anything we’ve ever seen in the franchise before or since. And it’s *terrifying.*

A common trope in Star Trek is “they were only trying to communicate!!1!” where we learn, belatedly, that a supposed enemy or alien monster wasn’t interested in harming our heroes, but that their form of life was so different that we interpreted their actions as aggression. Another trope of the franchise is our heroes using diplomacy and negotiation to defuse dangerous situations; talking down the Cardassians, Romulans, or Sheliak before a conflict can even break out. The Borg – prior to First Contact – completely ruled out all of that. They don’t talk, they don’t negotiate, they don’t want to be pals. They want to consume; to exploit technological and biological resources to add to their Collective. And you don’t get a say in that.

The Borg Queen opens up a channel to conversation and negotiation with the Borg, and was also a scenery-chewing bad guy in the mould of so many other villains of stage and screen, both in the Star Trek franchise and beyond. I’ll concede the point that the Borg Queen is one of Star Trek’s most memorable and iconic villains. But that’s not the issue. There didn’t need to be an individual Borg leader in order for the Collective to be so dangerous and threatening. Worse, the Queen actively detracts from the previously unique nature of the Borg, transforming them into just another enemy faction with an over-the-top leader.

This got worse in Voyager, where the Queen developed a weird relationship with Janeway and, in particular, Seven of Nine. The Borg Queen is supposedly a manifestation of the Borg Collective itself, in control of literally trillions of drones, tens of thousands of starships, and the biggest interstellar empire in the galaxy. Yet, for some reason, she obsesses over Picard, Janeway, and Seven of Nine in a way that never felt plausible or realistic. It continued the trend of making villains in Star Trek simultaneously more bland and more over-the-top. And, of course, it all came to a head in Picard’s third season, where the finally-defeated Borg Queen even yells out “noooo!” as she’s beaten, as if she were a second-rate supervillain from a cheap comic book.

The Borg Collective worked because it held up a dark mirror to a society just beginning to get started with computers, showing us how an over-dependence on technology could go awry. It played on similar tropes to zombies, fears of Cold War-era “brainwashing,” and more. The idea that every hero lost turns into another enemy to fight is a powerful one, and the thought of losing one’s mind and being turned against one’s friends is truly a fate worse than death for a lot of folks. But what made the Borg work was that they were incomprehensible, unstoppable, and far beyond Starfleet in terms of size and technology. Adding a scenery-chewing bad guy at the behest of a studio executive? It took away all of those unique qualities, set the stage for a noticeable decline in the quality of Borg stories, and just… ruined the Borg.

“Hot Take” #4:

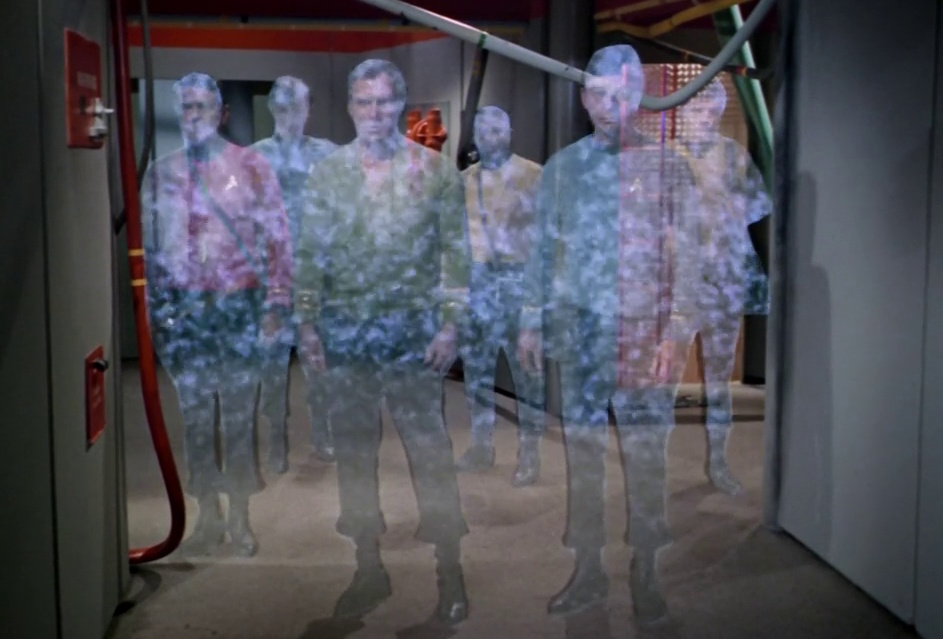

The transporter is more magic than sci-fi… which is why arguments about whether it “kills and copies” characters are kinda silly.

Of *all* the fictional technologies in the Star Trek franchise, none have become quite as controversial as the transporter. There’s a raging debate about how the transporter works, what happens to people who get transported, and whether they’re the same person, clones, or something else entirely. Some folks are adamant that the transporter basically murders and then clones anyone who steps into it, arguing that, if the transporter were ever to be invented in the real world, our current understanding of physics and atomic particles means that the person who steps out the other side of a transporter beam is basically a clone.

But here’s the thing: the transporter is probably the least-realistic of any of the major technologies we know of in Star Trek. There are proposals for faster-than-light communication via quantum entanglement. There are concepts for actual warp drive and other faster-than-light engines. There are realistic artificial gravity ideas that seem feasible. But a transporter? It’s basically magic wrapped in technobabble. That technobabble makes it *feel* technological rather than magical, but it’s the least-plausible of all Star Trek technologies. And for me, it’s one of those “you just gotta suspend your disbelief” things.

We don’t apply the same rigorous real-world quantum physics analyses to things like warp drive, do we? Not at the same rate, anyway, based on my engagement with the fan community. Yet, if you approach faster-than-light travel the same way as some pseudo-scientists and armchair physicists do the transporter, you pretty quickly find that it’s impossible, too. My point is this: Star Trek is science-*fiction*, and, as in all works of fiction, there comes a moment where you can either… go with a story and suspend your disbelief, or you can’t. Lots of things in Star Trek are totally fictional. Klingons. Phasers. Dilithium Crystals. And while I get the argument that we want the world of Star Trek to make sense, it’s more important to me that it remains consistent with itself, not that it has to conform to our current understanding of real-world science in every instance.

If Star Trek was constrained by real-world science all the time, that wouldn’t just affect the transporter! Starships at warp would have to deal with time dilation as they travelled faster than the speed of light. Energy weapons would be basically invisible. Starship battles would look a heck of a lot different, too. Can you imagine, in the Battle of the Mutara Nebula, if we had to sit in the cinema for eight weeks while the Enterprise’s torpedo slowly made its way, at sub-light speeds, towards the Reliant? That wouldn’t be a lot of fun, right?

There is a sub-genre of “hard” sci-fi, where real science matters a lot more than it does in Star Trek. And I daresay it’s true that you’d either never get a technology like the transporter there, or if you did, it’d be treated as some kind of existential horror. But Star Trek isn’t that kind of franchise, despite what some Trekkies like to think, and if we want to enjoy Star Trek episodes and stories on their own merit, we kinda have to accept some scientific inaccuracies and some of the franchise’s more magical and fantastical elements. The transporter is one such example.

I will say, though, that I totally get this argument, and when it’s made in a less-than-serious way, I don’t *object* to it, nor to having a discussion around it. But if someone’s gonna try to claim that it “ruins” Star Trek, or that the franchise needs to explain, in-universe, how the transporter works in detail, then that’s something I’m just flat-out not interested in. Most of Star Trek’s technologies benefit from a degree of vagueness, and the transporter is one of them. It can adapt to fit the needs of all manner of stories, and while there may be implications to the technology based on our current understanding of sub-atomic particles and physics… well, who’s to say that those implications won’t be overcome or proven wrong in the next few centuries? All it takes is a little bit of creative thinking to accept that the transporter works in exactly the way we see it work in episode after episode!

“Hot Take” #5:

Most pitches for new Star Trek shows from ex-actors (and a lot of fantasy proposals from fans, too) would be just *awful*.

Scott Bakula has been doing the rounds recently with his proposal for a “Star Trek: President Archer” series; a kind of sequel to Enterprise focusing on the early years of the Federation with Archer as its leader. Robert Duncan McNeill unironically pitched a Captain Proton show a few years ago. Michael Dorn spent years trying to convince CBS and Paramount to go for his “Captain Worf” idea. And those are just a handful of ideas for new shows, sequels, or spin-offs that I just… I really think wouldn’t be much fun.

Picard demonstrated that there can be a place for sequels in Star Trek – though it did so *very* imperfectly a lot of the time. But as we were just saying, modern Star Trek already relies excessively on legacy characters, so doing *more* Picard-type shows, focusing on characters like Seven, Janeway, Worf, or Archer… I think it’s just too much, especially right now. And without a hook nor a compelling reason for *why* any of these characters need to return, I think they’d struggle to tell engaging and interesting stories that would really justify bringing them back.

On the one hand, I get it. If you’re… well, to be honest, *most* ex-Star Trek actors, returning to the franchise is the best work you’re gonna get this decade – if not ever. And when the former ViacomCBS and Paramount corporations seemed to have been greenlighting Trek projects all across the board, you’ve basically got nothing to lose by putting a pitch together. But I think what Star Trek needs right now is to move on, to genuinely leave the past in the past. If there’s even a remote chance of a new series anytime soon, it should be set further along the timeline, in a new era, with new characters. Modern Trek has already overdone it with the legacy characters, in my opinion.

But that’s somewhat incidental. The blunt reality is that I don’t think I’ve seen a single one of these pitches that I actually liked, or that I felt had even the remotest justification for being created. Take Kate Mulgrew’s Janeway idea as an example. Between Voyager, Prodigy, and references to her in Picard, we’ve seen her entire arc… and then some. What could a hypothetical “Star Trek: Janeway” do for the character that we haven’t already seen? It would be a sequel for the sake of making a sequel… worse, it would be a sequel for the sake of cutting Kate Mulgrew a cheque.

I’m loathe to give studio executives *any* credit whatsoever – especially the brain-dead hacks who used to run the old ViacomCBS and Paramount corporations. But if there’s one thing I could say in defence of some of these folks, it’s that they recognised the obvious lack of quality (and lack of broader audience appeal) in these kinds of actor-led pitches and proposals. There’s an alternate timeline, perhaps, where the Star Trek franchise is swamped by a succession of disappointing sequel shows centred around one or two returning characters… and I just don’t see how any of that would be an improvement.

I’d also extend this to a whole lot of fan-made proposals and “fantasy” Star Trek shows, too – probably including some of my own! I’d have loved to see, for example, a series set aboard a hospital ship; ER in space. But let’s be honest, hardly anyone would be interested in that! There’s no shortage of ideas and proposals from fans for new Star Trek shows, sequels, and spin-offs, and while I will occasionally come across one that sounds genuinely interesting… most of them are absolute trash, and would be truly awful if they ever made it to the screen. This isn’t to say that the Star Trek franchise has got everything right in recent years – far from it. Look at the repetitiveness of Discovery’s storytelling as the show wore on, the bizarre decision to commission a Section 31 show, then re-work it into a TV movie, or making a half-kids show, half-sequel to a series from a quarter of a century earlier. But just because the folks in charge of Star Trek have made mistakes, that doesn’t magically make some of these truly awful-sounding pitches any better!

“Hot Take” #6:

Star Trek is, at a fundamental level, not the right fit for a serialised streaming TV show.

Since Lost premiered in the mid 2000s, and especially after Game of Thrones took the world by storm, most big-budget TV shows have gone down a serialised route, mandated by broadcasters and streaming platforms. And there have been some wonderful success stories with the serialised format… in other franchises. But when you think about what Star Trek is at its core – a franchise about exploring strange new worlds – that just doesn’t gel with the kind of serialised storytelling that has become the norm on streaming. And I think that’s a big part of why modern Star Trek has struggled.

A typical Star Trek series needs the freedom that only episodic storytelling can provide. It needs to be able to warp to a new planet every week, encounter new aliens, new villains, and new temporary allies. There can be character arcs and growth within that format – I’m not suggesting we go back to the days where something huge or traumatic would happen, only for it to be ignored in every subsequent story. But in terms of what Starfleet is and what almost all of our main characters do for a living… the only way to tell these kinds of stories, really, is to use that older, episodic style.

The only series where serialised storytelling had a chance of working was Deep Space Nine. A static setting with a large cast of secondary characters gave the franchise that opportunity. And I’m not averse to the idea of doing something like that again – DS9 is, on balance, probably my favourite series, and I’d like to see another Star Trek show set on a space station or even a colony. Both of those settings offer more potential for serialised storytelling.

But a show like Discovery, set on a vessel of exploration, needed the freedom of an episodic format to really shine. There were a few semi-standalone episodes across Discovery’s run, and I think most of them would probably rank as my personal favourites that the show produced. But for me, Discovery’s format – which was later recycled in Picard and even Prodigy – felt more like a constraint than an advantage. Blindly chasing the latest trend did not benefit any of the Star Trek shows that tried it, and it’s no coincidence that Strange New Worlds – which employs much more of an episodic style – is, in my view, far and away the best part of modern Star Trek.

Unfortunately, Starfleet Academy seems poised to repeat the mistakes made by Discovery, Picard, and Prodigy – telling a season-long, fully-serialised story with a “huge galactic threat,” a villain with a mysterious connection to a main character, and so on. It’s my sincere hope that, if and when Star Trek is revived on the small screen one day, we’ll get something closer to Strange New Worlds in terms of the kind of storytelling employed. Most Star Trek shows just aren’t a good fit for these kinds of serialised stories. And that’s before we get into how repetitive it is to have existential threats, scenery-chewing villains, and the like every single time.

Star Trek has *always* taken inspiration from the entertainment landscape around it, and that’s not inherently a bad thing. But in this case, the way streaming TV has gone over the past fifteen years or so has taken it in a direction that doesn’t suit the Star Trek franchise, and I wish the higher-ups had recognised that sooner. There’s scope to tell *some* serialised stories in Star Trek – I’m not saying it should never be attempted. But doing so at the expense of episodic storytelling in almost every case is why, for a lot of folks, the modern franchise hasn’t “felt like Star Trek.”

So that’s it… for now!

We’ve talked about six of my “hot takes” to mark the beginning of the 60th anniversary year – but there’s more to come! Starfleet Academy will premiere later this week (for some reason, Paramount-Skydance didn’t invite me to the premiere nor give me the episodes to watch early; wonder why?) My current plan for Starfleet Academy is to write a review of the two-episode premiere, then write a review of Season 1 as a whole after it concludes in early March. I don’t think I have enough in the tank for weekly episode reviews right now, I’m afraid, but I hope you’ll join me as I check out the premiere, at least.

And as we get closer to the anniversary, I’ve got a couple of ideas for episode re-watches and other pieces to celebrate this impressive milestone. I’m not 100% sure if Strange New Worlds Season 4 will be out this year, but if it is, I daresay I’ll be reviewing those episodes, too. And I’m always on the hunt for more Star Trek topics to write about, especially in an important year like this. So definitely check back!

Until then, I hope this has been a bit of fun – and not something to get too worked up or upset about! I enjoyed writing up these “hot takes,” and I hope you’ll take them in the spirit of good-natured fun as we come together to celebrate what makes Star Trek such a great franchise. See you… out there!

Most Star Trek films and TV programmes can be streamed on Paramount+ in countries and territories where the platform is available, and are also available on DVD and/or Blu-ray. The Star Trek franchise – including everything discussed above – is the copyright of Skydance/Paramount. This article contains the thoughts and opinions of one person only and is not intended to cause any offence.