Spoiler warning: There are spoilers ahead for Star Trek: Discovery Seasons 1-5. Spoilers are also present for the following Star Trek productions: Strange New Worlds Seasons 1-2, Picard Season 3, Prodigy Season 2, and pre-release info for Starfleet Academy.

Did Discovery’s “post-apocalyptic” take on Star Trek work as intended from Season 3 onward? If not… what went wrong? Why might a far future setting with a galaxy in ruins have been the wrong choice for this franchise? If another group of writers had tackled the same concept in a radically different way, could it have worked better? What does it all mean for Starfleet Academy? Those questions and more are what we’re going to ponder today!

Although Discovery has now concluded its five-season run, there are still topics to consider and debate. And it’s only now – after the series has concluded and we’ve seen three full seasons of its far future setting – that we can truly begin to wrangle with the “post-apocalyptic Star Trek” idea that began in Season 3. I held out hope for a while – particularly when Season 5’s marketing material and trailers seemed to be teasing a different kind of story – that Discovery might be able to do something creative, interesting, and engaging with this new idea. But, for me at least, post-apocalyptic Star Trek didn’t really work.

I think it’s worth discussing this subject for a couple of reasons. Firstly, Discovery was the franchise’s flagship series during its run. It brought Star Trek back to its small screen home after more than a decade in the wilderness, teed up the excellent spin-off Strange New Worlds, and for our purposes today, it also created this far future setting. Shooting forward in time centuries beyond The Next Generation, Picard, and even anything we’d seen in time travel episodes elsewhere in the franchise, Discovery had a completely virgin, unspoiled setting and time period for the writers and producers to craft.

Secondly, while Discovery may be over, there’s more Star Trek to come – at least for the next couple of years. A second spin-off – Starfleet Academy – intends to keep this far future timeline going, and it’s not impossible to think that Paramount might want to set new films or shows in this era, too. Given the issues Discovery had, it’s important to understand what worked about the setting and what didn’t – so future creatives can double-down on the positives while avoiding a repeat of the mistakes.

As always, a couple of important caveats before we go any further. This may be a controversial topic; Discovery has always elicited strong reactions from the Star Trek fan community (to put it mildly!) It’s worth keeping in mind that all of this is the entirely subjective opinion of one old Trekkie. I’m not claiming that I’m right and that’s that – different folks will have different opinions about some of these storylines and narrative concepts, and that’s okay.

If you followed along with my Discovery reviews, you’ll know that I’m a fan of the series on the whole – not any kind of hater. Some storylines worked better than others, and I pulled no punches in criticising episodes and narrative choices that I didn’t like. But I’m glad Discovery exists and remains a part of Star Trek’s official canon! The fact that we’re talking about whether the post-apocalyptic tone worked from Season 3 onwards – and what I personally didn’t like about it – shouldn’t be taken as me “hating” Discovery or any of its writers and producers. I share my opinion with the Star Trek fan community in the spirit of polite discussion.

With all that being said, if you aren’t in the right headspace to tackle a potentially controversial subject, that’s totally okay. This is your opportunity to jump ship if you’d rather not get into the weeds with Discovery and its “post-apocalyptic” tone.

To begin with, I think we need to consider why Discovery’s post-apocalyptic vision of the future exists at all. I tackled part of this question in a different article – which you can find by clicking or tapping here – but here’s the short version: Discovery wouldn’t have left the 23rd Century if the writers, producers, and executives were happy with the show. The decision to shoot forwards in time is, in my opinion, a tacit admission from the folks at CBS that setting Discovery a decade before Captain Kirk’s five-year mission was a mistake. It was an attempt to rectify that “original sin” which, some may say, came two seasons too late.

But leaving the 23rd Century behind didn’t mean Discovery had to arrive in a galaxy devastated by the Burn. That was a creative choice on the part of the show’s writers and producers; an attempt to transplant Star Trek’s core themes of hope for the future, optimism, peaceful exploration, and a post-scarcity society into a completely different environment. And to be clear: I don’t think Discovery’s writers lost sight of what those concepts were or what Star Trek had been, as some have suggested. But they misunderstood how important those things were to the foundation of Star Trek’s setting, and why it was so important to see a vision of the future where many of the problems of today have been solved. In attempting to be clever and subversive – or perhaps thinking they knew better – they robbed Star Trek of not only its most important defining feature, but also one of the key differences between Star Trek and most other popular sci-fi and fantasy worlds.

A post-apocalyptic setting clearly appealed to executives at CBS because of how popular it had proven to be elsewhere. From the late 2000s and through the entire 2010s, shows like The Walking Dead, Falling Skies, The 100, Jericho, The Strain, and 12 Monkeys had found critical and/or commercial success, as had films like Children of Men and Snowpiercer, and games like The Last Of Us and the Metro series. Star Trek has occasionally set trends in entertainment – but it’s also never been shy about following them. After two seasons of Discovery that had proven controversial – and crucially, hadn’t been a resounding success commercially – piggybacking on an apparently popular trend wasn’t an awful idea in principle.

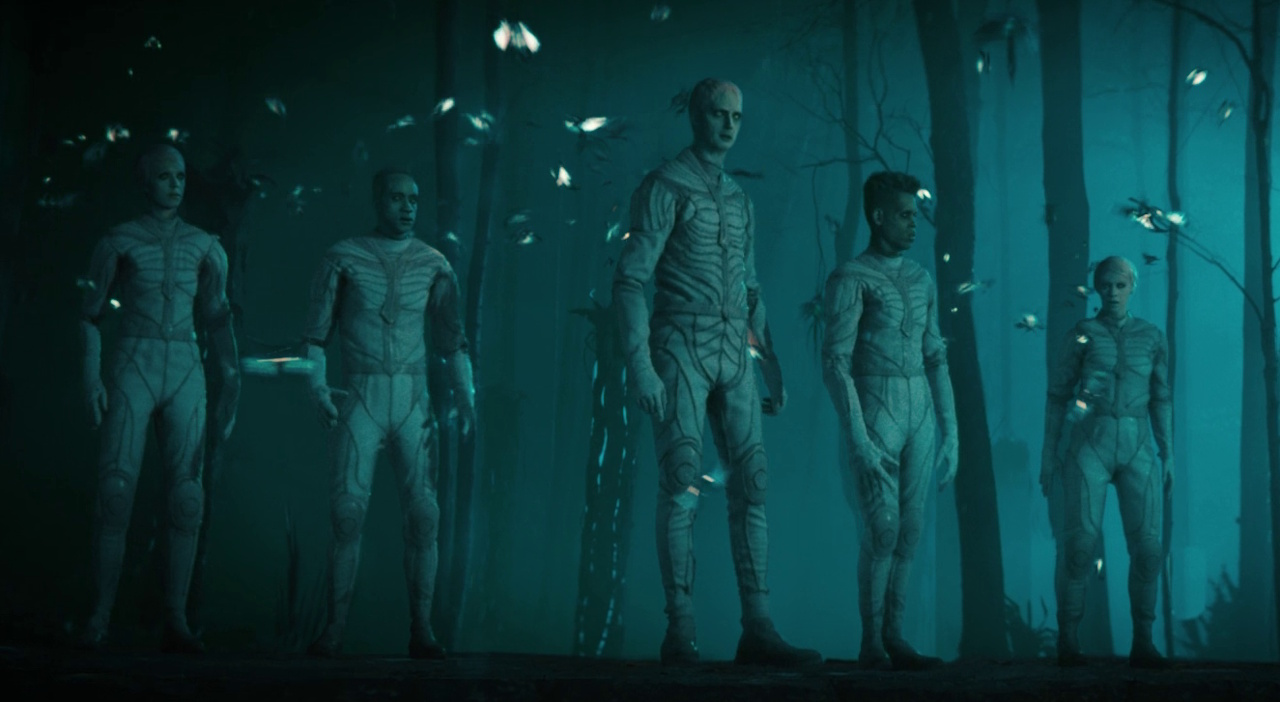

Discovery’s creatives wanted to take Star Trek’s foundational sense of optimism and hope and completely reframe it; using the same core ideas but in a radically different way. By taking away Starfleet and the Federation, and leaving much of the galaxy devastated, in ruins, or struggling for resources, there was potential – they believed – to tell stories about bringing people back together, finding hope in a bleak setting, and even considering the impact of this level of devastation on the crew’s mental health.

Image Credit: Frogland Archive

At the peak of the Cold War, with America and the Soviet Union staring each other down atop piles of nuclear weapons that could destroy the planet, The Original Series presented a peaceful future in which humanity had overcome those struggles. Later, in the 1990s, Deep Space Nine’s Dominion War didn’t show a devastated Federation on the brink of defeat, it showed good people struggling to save the “paradise” that had been built. These shows were different from one another in many ways – but at the core, one of the foundational pillars of Star Trek is that the future is bright and it’s going to be worth fighting for.

This is something fundamental to Star Trek; it’s a huge part of what makes the franchise what it is. And there’s a massive difference between a show that says “humanity has overcome all of these obstacles, so let’s explore the galaxy” and one that says “everything is ruined but we can rebuild.” These two narrative ideas both have the themes of optimism and hope – but they’re very different kinds of optimism and hope, and they’re presented in totally different ways. It’s not so much that one works and the other doesn’t; see the list of post-apocalyptic media above, all of which use those themes and ideas in some form. But in this case, the post-apocalyptic setting took away something foundational from Star Trek’s setting, utterly transforming Discovery into a completely different kind of series.

Here’s the bottom line: Discovery didn’t do anything exceptional with its post-apocalyptic setting. I still think such a massive change to the core of Star Trek would’ve attracted criticism even if the show’s writing had been exceptional from Season 3 onwards, but the simple fact is that it wasn’t. There were some decent episodes and creative ideas in the mix, don’t get me wrong… but Discovery’s biggest problem both before and after this switch to a post-apocalyptic setting was that its storytelling was small, repetitive, and overly reliant on levels of interpersonal conflict and relationship drama that we seldom get outside of soap operas. In short, Discovery’s post-apocalyptic setting turned out to be nothing more than background noise; set dressing for less-interesting stories to play out in front of.

Such a huge change to Star Trek’s galaxy and the damage done to the Federation needed more time in the spotlight and it needed to serve a purpose. In Season 3, part of the story focused on the Burn and figuring out what happened. This story was an ultimately frustrating one, with dead ends and red herrings before arriving at an ending that no one could have predicted. Season 3 teased viewers with a mystery, stringing us along and seeming to reveal clue after clue in different episodes, only to then pull a bait-and-switch to something out of left-field that didn’t feel properly set up. It was pretty annoying – and I know I wasn’t the only one who felt that way at the time.

Worse, though, was that Season 3 spent such a long time on what felt like unimportant fluff in comparison to the Burn. The first episodes of the season showed us how far the Federation had fallen; humans on Earth couldn’t even travel as far as Titan, within their own solar system – such was the shortage of fuel and supplies. Earth and Vulcan had both withdrawn from the Federation, and Starfleet wasn’t able to contact many of the Federation’s outlying member worlds and colonies. But instead of exploring what this could mean and telling a story about figuring out what went wrong and how to fix it… Discovery’s writers told half-baked stories about depression, Burnham’s on again-off again relationship with Starfleet, Book and Burnham’s love affair, and more.

To be clear: I don’t think the post-apocalyptic setting would’ve been the right choice regardless, for the reasons outlined above. But Discovery’s writers didn’t even give that premise or the far future setting a chance to win me over. Instead, they tried to jump right back in with stories about Michael Burnham: Chosen One™ – and it just fell so incredibly flat.

Image Credit: IDW Publishing/Paramount

There was a metaphor buried in the far future setting that could’ve been timely. But the end of Season 3 ruined it. By taking one of Star Trek’s core technologies – warp drive – and saying that the galaxy as a whole was running out of fuel, there was a chance for Discovery to do what Star Trek has always done: use a sci-fi lens to examine a real-world issue. We rely too heavily on limited supplies of fossil fuels here in the real world, and Season 3 could’ve made a point about the need to innovate, invent new methods of travel and power generation, and tie those issues into the theme of rebuilding and coming back stronger. That could’ve been a powerful story if done well, and it also could’ve finally found a proper use for Discovery’s most controversial addition to Star Trek: the spore drive.

But the discovery of a near-unlimited cache of dilithium toward the end of the season totally undermined all of that. It would be like writing a story about Earth running out of oil and humanity coming together to build new vehicles and methods of power that don’t rely on fossil fuels… only for the story to end with a massive untapped oilfield being discovered. This mixed messaging, and unwillingness to commit to telling stories that could’ve taken advantage of this kind of setting, really tripped up Discovery. The most powerful – and potentially interesting – ideas that could’ve been explored in this kind of setting were just left feeling flaccid and half-hearted.

Many post-apocalyptic shows and films tell character-focused stories, and these settings can lend themselves to high-stakes drama. But most of the time, the environment that the characters are confronted with – whether that’s a zombie apocalypse, an ecological disaster, a pandemic, or something else – is at least part of the cause of the tension and interpersonal conflicts. A character like The Walking Dead’s Governor is who he is because of the world he inhabits. Many of the arguments between characters in shows like The Strain or films like City of Ember happen because of the environment they’re in. Even relationships can begin – or be ended – by the stresses of a post-apocalyptic life, as we see in films like Shaun of the Dead or shows like 2008’s Survivors. But Discovery couldn’t even get this right most of the time.

Most of Discovery’s storylines in the far future could’ve worked just as well – better, even, in some cases – without the post-apocalyptic backdrop. Seasons 4 and 5 in particular are both in this camp. The Dark Matter Anomaly that devastated parts of the galaxy would’ve arguably been more impactful if it had been attacking a fully-intact Federation. And the threat of the Breen attack and the Progenitors’ device in Season 5 is the same. They would’ve worked in the same way Deep Space Nine’s Dominion War did: as threats to Star Trek’s post-scarcity technological “paradise.”

Smaller storylines are also in this camp. Detmer’s half-arsed mental health story in Season 3, Culber’s equally weak depression in Season 4, Adira and their quest to help Gray be seen again, Burnham and Book’s mostly awful on/off relationship, the Ni’Var stories involving Romulans and Vulcans working together… would any of these have worked less well, or even been noticeably different, without the Burn and the devastation it had caused? Or would they have been able to play out almost exactly the same, beat for beat?

Taking the idea of societal collapse as a starting point, Discovery’s writers could have tied in themes of mental health. The character-focused storytelling that they wanted, with high levels of drama and plenty of “therapy-speak,” was potentially well-suited to the post-apocalyptic environment they’d created. But there was almost no attempt to link these two ideas; instead, characters would suffer or sulk for reasons completely unconnected to the world they found themselves a part of. This feels like a horrible missed opportunity considering the kind of show Discovery’s writers and producers wanted it to be.

For some reason, since Star Trek returned to the small screen, there’s been an insistence on serialised storytelling – but only for one season at a time. Self-contained narrative arcs have been the order of the day, which meant that the Burn, its origin, and crucially, its aftermath were only really in focus in Season 3. A couple of clips at the beginning of Season 4 – as well as a handful of throwaway lines of dialogue here and there – referenced the Burn, but for the most part, it disappeared after Season 3 was over.

There is a partial justification for this: Discovery’s production team were never sure whether cancellation was coming. If there might’ve been one thing worse than a devastated galaxy and an apocalyptic event, it would be leaving the reason for all the destruction unexplained with the show abruptly going off the air! So in that sense, I get why those decisions were taken. Star Trek was still finding its feet in a new entertainment landscape, CBS and later Paramount were on shaky ground amidst the “streaming wars,” and there was no guarantee of a renewal. Setting up the Burn and explaining it in a single season makes sense in that context.

But dumping the Burn after Season 4, and not doing more to explore the consequences of this massive event… that makes less sense to me.

Star Trek in its heyday was a primarily episodic franchise. There were season-long arcs in Deep Space Nine and Enterprise, as well as Voyager’s seven-year journey back to the Alpha Quadrant. But even in those frameworks, episodic storytelling was still the order of the day for Star Trek. I think it’s no coincidence that the best episodes Discovery told were the ones that were somewhat standalone. Episodes like Season 2’s An Obol for Charon, Season 3’s Terra Firma, Season 4’s Choose to Live, and Season 5’s Face the Strange are all at least partly self-contained affairs. Strange New Worlds has also taken on a much more episodic tone – something that has made that series an absolute joy to watch.

At the start of Season 4, I hoped that Discovery would go down a more episodic route. The Burn could be a starting point, and Discovery could’ve hopped to different planets across the Federation as the galaxy began to rebuild from its aftermath. A story of bringing hope to people who’ve been struggling to get by could have been exceptional if handled well, and the Burn – despite the issues it caused for Star Trek as a whole – was the perfect entry point for telling stories like that. Switching up Discovery to become a more episodic show could’ve given more of the cast a chance to be in the spotlight, with episodes focusing on different planets and different people every week.

To me, this feels like an open goal; a golden opportunity for Discovery to prove the haters wrong. It was a chance to do something meaningful with the Burn and the post-apocalyptic setting that Season 3 – with its unfolding mystery and close focus on Burnham – didn’t really have much time for. Moreover, it would’ve been a great way to explore other aspects of this 32nd Century setting, catching up with factions and races from past iterations of Star Trek.

Despite spending three seasons in the far future, we didn’t so much as glimpse a Klingon. Races like the Ferengi were seen in the background and there were throwaway lines that mentioned the Borg and the Gorn, but none of them ever showed up on screen. Given that the devastation of the Burn was supposedly a galaxy-wide thing, Discovery did absolutely nothing to show us what some of the most iconic and beloved factions in Star Trek were doing in this era or how they were coping. And then there’s the elephant in the room: the Burn was, in a roundabout way, caused by a Federation ship operating under orders from Starfleet HQ. What would the likes of the Klingon Empire or the Cardassian Union do if and when they learned that truth?

Let’s draw the bare outline of a potential story that would take the Burn as a starting point, tie in one of Star Trek’s well-known factions, and use it as a springboard for some character-focused storytelling. This is just a thought experiment, but I think it’ll illustrate the point I’m trying to make!

After discovering the truth behind the Burn and ensuring it won’t happen again, Captain Burnham and the crew are tasked with jumping to the Klingon homeworld, where a Federation ship has gone missing. Upon arriving at Qo’noS, Discovery is confronted by angry Klingons telling them to leave, and they learn the missing ship has been impounded and its crew are being held. The Klingons, whose empire has fractured and who have been suffering the effects of the Burn for a century, blame the Federation for what happened – and in addition to holding one ship captive, they’re massing for war.

This would be hugely triggering for the crew of Discovery – they’re veterans of the 23rd Century Klingon war, a war Burnham still blames herself for causing. It brings back horrible memories for her and another member of the crew, and they have to wrangle with those feelings while trying to avert a war. The Klingon fleet is low on dilithium, but they’re willing to expend the last of their dwindling resources on a quest for vengeance. It falls to Burnham, Admiral Vance, and perhaps President Rillak to talk them down – offering to re-instate the Khitomer Accords and share the cache of dilithium with the Klingons.

An episode like this would take Discovery’s post-apocalyptic setting and actually do something with it – using it as the driving force for all of the tension, drama, and personal conflict in the story. The Burn devastated the Klingon Empire and they blame the Federation. Burnham has to come face-to-face with the Klingons for the first time since the war, trying to prevent another conflict while also wrangling with the trauma of the last one. Crucially, we’d get to explore one of Star Trek’s most iconic alien races and catch up with them centuries after we last saw them.

If Discovery had told stories like this one, which took the post-apocalyptic tone as a foundation, I think it could’ve been more successful. At the very least, such stories would’ve made the Burn and its aftermath more meaningful, and we’d have gotten a broader exploration of the consequences. Life in a post-apocalyptic setting was never really in focus in Discovery, and aside from the first two episodes of Season 3 and a handful of other scenes here and there, it never stuck the landing. I’m not saying my story outline as proposed above is perfect, but it would at least have leaned into this post-apocalyptic idea and done something more with it.

Instead, much of the rebuilding and diplomacy seems to have taken place off-screen – if we’re to imagine it happened at all. After defeating the Emerald Chain and securing the Verubin Nebula and its dilithium, Starfleet and the Federation seem to have instantly rebuilt, with very little mention of the Burn and its century-long aftermath in Seasons 4 and 5. Considering how massive and transformative this event was for the galaxy, that’s just not good enough. If there was ever a place where the old Creative Writing 101 adage “show, don’t tell” was important, it was here!

Discovery would still have faced an uphill battle, I fear. Ruining the galaxy, devastating the Federation, and forcing survivors to scrounge for resources for decades feels antithetical to Star Trek in so many ways. But if there had been a conscious effort to lean into this idea and use it as a springboard for storytelling that was well-suited to a post-apocalyptic environment, it could at least have worked better or been less bad. The combination of a post-apocalyptic setting with stories that just didn’t fit made things noticeably worse.

That’s before we come to “the prequel problem,” though.

In brief, Discovery is set in Star Trek’s prime timeline – no matter what some fans might say or what head canon explanations we have, at time of writing Discovery remains in the prime timeline. Everything we’ve seen on screen from Enterprise in the 22nd Century to Picard at the dawn of the 25th takes place in this same setting – which means that the prime timeline is destined to be devastated by the Burn. Going back to watch older episodes of Star Trek doesn’t feel much different, at least not to me, but the Burn and all the chaos and ruination it caused is sure as heck going to taint future stories.

Take Picard’s third season as an example. Admiral Picard and his crew had to come together to defeat a conspiracy targeting Starfleet – and after a hard-fought struggle, they won and saved the day. But because Picard Season 3 premiered after we learned about the Burn in Discovery… at least some of its impact was blunted. Now, don’t get me wrong: Picard Season 3 wasn’t spectacular in its own right. But it was the best and certainly the most complete and coherent story that series had to offer – and yet because we know the Burn is coming in the future, it almost doesn’t matter what Picard and his friends did.

You can look at this problem in two ways.

Firstly, we know in the back of our minds that the Federation will survive – no matter how high the stakes may be in a future project. When Admiral Picard was staring down Vadic and the Borg-Changelings, we knew that, somehow, they’d prevail and Starfleet would win the day. This is the basic problem many prequels have; it was present in multiple episodes of Enterprise, for example, even when that show was at its best.

Secondly, anything our heroes do is rendered somewhat impotent – or at least it’s tainted because we know that, no matter how hard they may work to save the day, the Burn’s gonna happen anyway. Earth and Vulcan will leave the Federation, dilithium will be in short supply, the galaxy will be in ruins, and it will be decades before rebuilding can begin in earnest. Any future story set in the prime timeline – whether it’s Strange New Worlds with its Gorn conflict, Picard’s battle against the Borg, or whatever happened at the end of Prodigy that I still haven’t seen – is a direct prequel to the Burn and the events of Discovery’s third season. Knowing that, even on a subconscious level, is a constraint on any story that aims to raise the stakes.

Star Trek exists in – to use a modern term – a persistent shared universe. With the exception of the Kelvin films, which are off to one side, every other show and film exists in the same timeline, and no other series until Discovery has done so much to change the trajectory of that timeline for all of the others. By leaping forward by centuries, and then enacting this massive, galaxy-altering event, Discovery’s writers definitely left their mark on Star Trek. But like a crudely-graffitied penis on the wall of a bus shelter, it’s not exactly a mark that the rest of us wanted to see.

If Discovery existed in a vacuum – as it arguably did at the start of its first season – then perhaps I could understand this change a bit more. It would still be a massive change, and it would still be a constraint on future episodes in a way no other storyline arguably has been. But at least if Discovery were the only Star Trek show in town, racing into the future and depicting an event on this scale would’ve been more understandable and less… selfish.

Image Credit: Frogland Archive

Discovery’s third season was in production alongside Picard, Lower Decks, Prodigy, Section 31, and also while pre-production work was happening on the pitch for what would eventually become Strange New Worlds. The show’s producers and writers went out of their way to assure fans that Discovery remained in the prime timeline – and that, by extension, the world they were building in Season 3 is the ultimate destination for the prime timeline. And then, either ignorant of the impact it would have or not caring about it, they went ahead and wrote a story that not only altered the entire galaxy for their own show and any potential spin-offs, but for every other Star Trek show, too. Everything from Strange New Worlds to Prodigy became, by default, a prequel to Discovery. And because Discovery’s writers don’t do half measures, they went all-in on the Burn – devastating the entire galaxy, basically ending the Federation as a faction for decades, and utterly transforming Star Trek in the process.

In order for there to be a post-apocalyptic setting (which Discovery largely ignored after the first couple of episodes of Season 3) there had to first be an apocalyptic event. Because Discovery has never turned down the tempo or lowered the stakes, this event naturally had to impact not just the ship and crew, nor even the Federation, but the entire galaxy. And the consequence of this choice is that every subsequent Star Trek production, no matter how hard they try to ignore it, will take place in a pre-Burn galaxy. The Burn is locked in; it’s the direction of travel for the Federation and Starfleet. Not only is that a massive constraint on future stories… it’s also incredibly depressing for a franchise that has always been about a hopeful and optimistic depiction of humanity’s future.

When we talked about “head canon” a few weeks ago, I argued that it might be better for Star Trek as a whole to quietly push Discovery’s far future into an alternate timeline. That doesn’t mean abolishing it altogether, but if a future episode – say in the upcoming Starfleet Academy series – were to incorporate that… I think it would be for the best. Star Trek, in my view, ought to do more with the 25th Century setting established by Picard, but the Burn and Discovery’s post-apocalyptic future hangs over any potential new shows or films right now.

Speaking of Starfleet Academy, what does this all mean for the upcoming spin-off?

A series set at Starfleet Academy has been talked about for decades. Gene Roddenberry had the idea originally; his version of the show, as conceptualised in the late ’60s, would’ve seen Kirk and Spock meeting for the first time. Picard’s second season also teased us with a glimpse of the Academy around the turn of the 25th Century – and Prodigy also included similar themes in its second season. But this version of Starfleet Academy has been conceived as a spin-off from Discovery, not only set in the same time period but also bringing in several regular and recurring characters. The likes of Reno, Admiral Vance, and Tilly will be joining the show from Discovery.

Photo Credit: City of Los Angeles/L.A. Times

I could spend the next few paragraphs lamenting Starfleet Academy’s place in the timeline and explaining why I think it’d work better in the late 24th or early 25th Century. But let’s not do that, eh? Instead, let’s talk briefly about how Starfleet Academy could be more successful with this post-apocalyptic setting than Discovery was.

First of all, let’s try to move back toward episodic storytelling. Look at what Strange New Worlds is doing – it’s possible to mix standalone stories with season-long arcs, and that blend works so much better than anything Discovery or Picard did. That doesn’t mean you can’t have a villain or a big, explosive storyline, as Strange New Worlds has repeatedly proven. It would be so much closer to what Star Trek has been in the past – and, I would argue, much closer to what fans want to see from this franchise.

Next, if Starfleet Academy is going to be set in this post-Burn era, the show really needs to lean into that in a way that Discovery didn’t. The show’s blurb talks about how the Academy is re-opening for the first time in decades… so that needs to be a big storyline. As the galaxy begins the slow process of recovery and getting “back to normal” after decades of decline, devastation, and depression, what does that mean for the new cadets, their families, their instructors, and their homeworlds? How has the environment these kids grew up in impacted their lives? Star Trek often does storytelling by analogy – so this could be a way to examine the real-world impact of the covid pandemic on education, just as an example.

Finally, I’d like to see an examination of the consequences of this galaxy-wide event on at least one other faction. Perhaps Starfleet Academy’s villain – who will be played by veteran actor Paul Giamatti – could be a member of a familiar race or faction seeking revenge for the Burn’s impact on his homeworld. At the very least, the Burn and the devastation it caused should be a significant factor in explaining who this character is and what motivates them. Having to survive in a broken, shattered world takes a toll – and that could explain why this villain is as bad as he is.

Discovery did very little of that. Most of the show’s villains in Seasons 3, 4, and 5 weren’t bothered about the Burn or the post-apocalyptic landscape. The only exception, really, was Zareh; I at least felt that – over-the-top though he was in some respects – he was shaped by the world he inhabited. The rest? Generic, scenery-chewing bad guys who could’ve easily been part of a totally different story set in another era – or another franchise, come to that.

I don’t think Starfleet Academy can really “save” Discovery. By that I mean I don’t think we’re going to look back at the Burn and Discovery’s take on this post-apocalyptic setting after a couple of seasons of Starfleet Academy and re-frame it or change how we think about it. But there is potential, if I’m being as optimistic as I can be, for the new series to make more of this setting than Discovery did, and to perhaps use the post-apocalyptic tone in a different and more successful way, a way better-suited to the environment that the Burn and its aftermath created.

At this point, you can probably tell that I’d never have given the green light to a storyline like the Burn if I’d been in charge of the Star Trek franchise in the late 2010s! A post-apocalyptic tone clashes in a fundamental and irreconcilable way with Star Trek, taking away one of the franchise’s core beliefs and the main way it differentiates itself from other sci-fi properties. Even if the storytelling in Seasons 3, 4, and 5 had been stronger, this transformational change to what Star Trek is would have still been a hurdle; even the best narrative concepts and ideas that I can think of would’ve struggled.

But the truth is that, while Discovery did manage some solid episodes after arriving in the far future, the main story arcs weren’t all that spectacular. The Burn itself was a frustrating mystery that had too many dead ends and red herrings, and storytelling after Season 3 completely sidelined not only the Burn but the post-apocalyptic environment that it left in its wake. Discovery’s writers, in a rush to do other things and tell different stories that mostly focused on one character, didn’t do anywhere near enough to justify the Burn and the massive impact it had on the world of Star Trek.

In one of the first pieces I ever wrote here on the website, back in January of 2020, I warned that a post-apocalyptic setting might not be the right choice for Star Trek. But I gave Discovery a chance to impress me and to do something with that idea that I might not have been expecting. Unfortunately, I don’t think the show really did that. Most of its storylines – both big and small – didn’t need a post-apocalyptic setting to work, and the setting itself fundamentally altered Star Trek – not only for Discovery, but in a way, for every other show, too. One of the core tenets of Star Trek since its inception had been that humanity could overcome the struggles of today and build a better future. Discovery took that better future and upended it – really without a good reason or a narrative that justified something of that magnitude – and in doing so, changed the entire franchise. Sadly, I feel this was a change for the worse.

“Post-apocalyptic Star Trek” was wrong in principle and wrong in practice. It misunderstood why themes of hope and optimism worked in the franchise in the first place, it took away one of the foundations upon which successful Star Trek stories had been built for more than half a century, and it seems to have come about from an unfortunate mix of corporate leaders wanting to jump on a successful trend and writers who thought they were smarter and more creative than those who came before them. While Discovery didn’t abandon or lose sight of the themes of optimism and hope that had been so important to the franchise, it bastardised them and used them in completely different – and too often ineffective – ways.

Moreover, “post-apocalyptic Star Trek” was executed poorly. The Burn – the event that caused all this devastation – unfolded in a frustrating way in Season 3, and I got the sense that for more than a hundred years, everyone in Starfleet had just been sitting on their hands as the world crumbled, waiting for Michael Burnham: Chosen One™ to swoop in, provide all the answers, and save the day. The Burn and its aftermath was then largely ignored in Seasons 4 and 5, despite offering the series – and the franchise – a chance to tell some genuinely interesting stories that could’ve expanded our understanding of this far future setting. By refusing to lean into the post-apocalyptic idea, Discovery’s writers failed to take advantage of the storytelling potential they had created.

Next, “post-apocalyptic Star Trek” impacts the rest of the franchise – from The Original Series to Picard. All of these shows now take place in a pre-Burn world, changing the way we understand them and perceive them on repeat viewings. For new Star Trek stories produced in the years ahead, this is going to be a lot worse because they’re basically all prequels to Discovery and its post-apocalyptic vision of the future. That knowledge challenges future stories and puts a brake on them in a way we haven’t really seen before.

Finally, “post-apocalyptic Star Trek” is likely going to be a constraint on Starfleet Academy. I want to be hopeful and optimistic about that series – and I have no doubt that, just like Discovery, there will be at least some fun and creative episodes in the mix. But the backdrop to the show is still a galaxy devastated by the Burn, and I don’t really have confidence in the current production and writing team at Paramount when it comes to doing something meaningful with that. If Starfleet Academy only pays lip service to Discovery’s post-apocalyptic world before racing off to do another “the entire galaxy is in danger!” story, it’ll feel like a waste. If that’s the kind of story the show’s writers want to tell, why not set it in a different time period that might be better-suited to that kind of story?

At the end of the day, a post-apocalyptic setting works for some stories and doesn’t for others. For the stories Discovery’s production team wanted to tell, it just wasn’t necessary for the most part – especially not after Season 3. Unlike other one-off ideas in Star Trek that the franchise has been content to brush aside, this one was so transformative and so utterly changed what Star Trek’s galaxy looks like that walking away from it isn’t possible. There just doesn’t seem to have been any kind of plan for where to take the series after Season 3 or how to use the post-apocalyptic setting to tell stories that wouldn’t have been possible in other iterations of the franchise.

So let’s answer the question I posed at the beginning: what went wrong? Fundamentally, “post-apocalyptic Star Trek” wasn’t a good idea as it deviated too far from the franchise’s foundations and roots. It was executed poorly, with most stories either ignoring the post-apocalyptic setting outright or not using it to inform characters or narrative beats. And it relegates any future production set after The Next Generation era but before Discovery’s third season to the status of a prequel, with all of the problems that can bring.

I don’t hate Discovery. There are some genuinely great episodes in the mix, including after the show shot forwards in time. Coming Home, for example, really hits a lot of the emotional notes that it aimed for, especially in the scenes and sequences set at Federation HQ and around Earth. Face the Strange was creative and fun, and a story like Choose to Live felt like classic Star Trek in the best way possible. But given how the show didn’t lean into this post-apocalyptic setting in a big way, devastating the Federation, Starfleet, Earth, and the entire galaxy just doesn’t sit right. It didn’t come close to finding a narrative justification, and given the scale of the change and the resonating impact it will continue to have… that’s not good enough.

Star Trek: Discovery Seasons 1-5 are available to stream now on Paramount+ in countries and territories where the platform is available. The series is also available on DVD and Blu-ray. Star Trek: Starfleet Academy is in production and will premiere on Paramount+ in the future. A broadcast date has not yet been announced. The Star Trek franchise – including Discovery and all other properties discussed above – is the copyright of Paramount Global. This article contains the thoughts and opinions of one person only and is not intended to cause any offence.