Spoiler Warning: There are spoilers ahead for Silo Seasons 1 & 2.

In 2023, I awarded Silo’s first season the highly-coveted Trekking with Dennis Award for best TV show of the year. It beat off Star Trek: Picard’s third season – which was, in hindsight, probably that show’s best offering. If you know me, you’ll know I’m a Trekkie and a big fan of Jean-Luc Picard – so Silo must’ve been pretty darn good, then! It’s no exaggeration to say that I was really excited for Season 2 and the continuation of this engaging sci-fi mystery story.

It can be difficult to render judgement on the middle part of a fully-serialised story, so that’s a big caveat to everything we’re going to talk about. With Silo confirmed to be returning for two more seasons, we may look back at Season 2 with that context and revise some of these talking points and criticisms – and I wanted to be clear about that. With that out of the way, here’s the headline: Silo Season 2 was good but not great. One side of the story was a thrilling, enigmatic mystery populated by a wonderful cast of characters. The other felt like an overblown video game side-quest, complete with unnecessary stumbling blocks that seemed to exist only to slow things down, and was padded out with a handful of very barebones, one-dimensional characters.

In short, Season 2’s good side was let down by its less-good side.

So… which side is which? Unfortunately, I found Juliette’s story this time to be the weaker one. And that’s such a shame, because Rebecca Ferguson – who also gets an executive producer credit for Silo – has put in a fantastic performance across both seasons of the show. Last season, Juliette was at the centre of the story, unravelling the mysteries of the silo piece by piece. But this time, she was isolated from most of the rest of the cast, trapped in her own little narrative box. And that box, for me at least, felt like it was mostly comprised of unnecessary hurdles to a story that was almost instantly a “back-and-forth” that aimed to shuffle Juliette right back to the first silo.

On the other side of things, the story of the rebellion in the Down Deep, complete with double- and triple-crosses, as well as Sims’ scheming and Bernard and Lukas trying to uncover more of the silo’s secrets… that was all fantastic. These characters, who we met last time and have more of a foundation to build on, all felt real, their actions seemed to flow naturally from the circumstances they were in, and it was a truly gripping and fascinating mystery with stakes. Given that we know the world immediately outside the silo is still deadly and toxic, the danger to everyone was communicated well – and having gotten invested in these characters and their world, that gave this side of the story a lot more weight.

Stepping back from the moment-to-moment narrative beats, Silo has constructed a world that feels – to me, at least – like a dark mirror of the United States. Leaders are left to rely on increasingly unclear instructions left for them by the nameless “founders,” communicated through a legal document that, for many in the silo, has taken on the status of scripture. I don’t know if you’re familiar with the term “American civil religion.” It’s a theory in American Studies/sociology that posits many Americans view documents like the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights as akin to scripture, with some of the founding fathers elevated to the positions of prophets. It’s an interesting idea, and one far too complex to detail in a few sentences. Whether you buy into it or not in the real world, Silo is definitely drawing on similar themes and concepts for its depiction of its underground society.

Silo also holds up a mirror to our modern-day surveillance society. Cameras are everywhere in the underground city: in people’s homes, in common areas, and workplaces. And spying on the citizens are a hidden group who seem to exist outside of the official heirachy and structure of the government, reporting directly to the mayor. As a metaphor for CCTV, facial recognition, and even online surveillance by the likes of the NSA, you could hardly get more explicit!

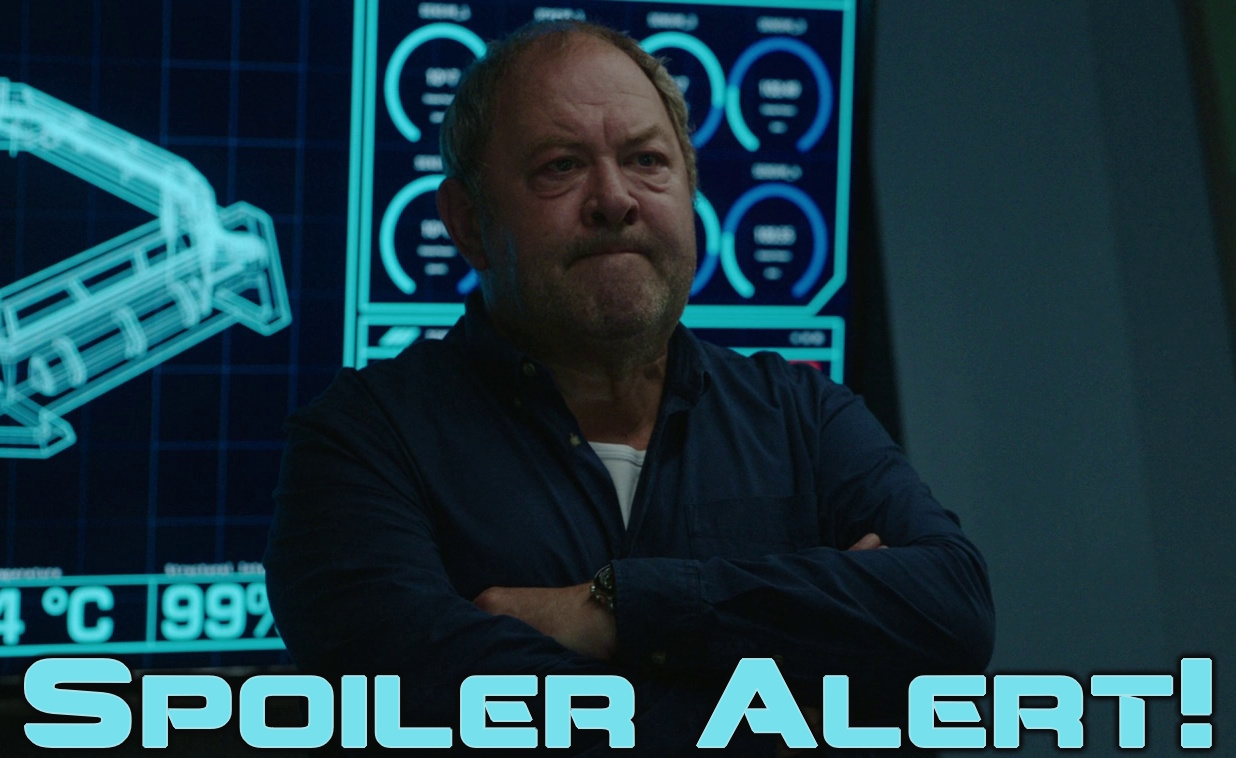

Both of these feel pretty timely. Silo goes to town with the idea of governments spying on their citizens – without their consent or knowledge. The dangers of such a sophisticated spyware network are obvious, including the ease with which someone could use that knowledge to become a dictator or autocrat, and we get to see that through Bernard’s characterisation. I read Bernard as someone who is out of his depth, but tries to use the immense power at his fingertips to retain – or regain – control of the situation as it begins to spiral. Again, there are real-world parallels there.

Silo also wants to reflect a class divide: the “Up Toppers” and “Down Deepers” representing the upper and working classes respectively. Becuase the action in Season 2 mostly focused on the mechanics and engineers on the lower levels, I don’t think we got as much of a look at the way society differs on the upper levels of the silo. We caught glimpses of it when we saw the larger, better-furnished apartments of people like Bernard and Judge Meadows, but with fewer characters in focus there was perhaps less of this in Season 2 than there had been in Season 1. The class war angle was interesting, though – and another place where Silo was clearly drawing on real-world issues for inspiration.

Juliette’s dramatic exit from the silo at the end of Season 1 left her friends and former allies on edge. By refusing to clean the camera and walking out of sight, she inadvertently left people believing that the world outside is safe – and we know that it isn’t. Arriving at a nearby abandoned silo, Juliette comes to learn the potential consequences of this: the rest of the citizens will rebel and try to break out, resulting in their deaths. This kicks off her story of… needing to immediately get back to her original silo.

I gotta be honest: I already felt this was a pretty weak setup. Having survived when survival seemed impossible and escaped from tyranny… all Juliette is left with is “I need to go back right now,” seeking to save her friends. As the setup for what was ultimately a slow storyline that seemed to spin its wheels too much, I was underwhelmed from almost the first episode. Then, things seemed to plod along, with Juliette teasing tiny pieces of information out of the mysterious sole survivor of this silo… only to belatedly learn that there were several other younger survivors, too. She apparently didn’t notice them or their settlement while exploring.

These younger survivors were pretty uninteresting, and their storyline came too late in the season to give most of them any real depth or interest. Audrey, whose sole defining trait seemed to be that she wanted to take revenge for the death of her parents, instantly gave up on that. And the others – Eater/Hope and Rick – got even less background than that. I struggled to believe that these characters had really been living their whole lives in the ruins of this silo, trying and failing to break into Solo’s vault and scratching together whatever food they could.

Silo just didn’t give these characters enough depth, and what little story was afforded them seemed to evaporate pretty quickly. For no other reason than “maybe don’t,” Audrey abandoned her apparent lifelong mission to seek revenge for the death of her parents, and for no other reason than “maybe open the door though,” Solo abandoned his lifelong mission to keep the door to the vault sealed. It wasn’t even clear that Solo knew anyone else was still alive inside the silo – which might’ve been useful information. Had Audrey and Rick ever visited the vault door? If so, why’d they leave their parents’ corpses unburied? And how did their settlement have power when it was explained that only the IT department – at least one level below – had its own power source and the rest of the silo’s power was out? There are a few too many contrivances, cut-down moments, and characters lacking depth on this side of the story for my liking.

And that’s part of what gives it a “video game side-quest” feel. Every time Juliette seemed to get close to her new goal of returning to her original silo… something would get in the way. First it was finding a replacement suit. Then it was Solo holding her suit hostage until she activated an underwater pump. Then it was the kids kidnapping Solo. Then it was Juliette and Eater/Hope having to search for the code to get into the vault… it just went on and on. Solo had potential as an interesting character, and there were moments of that on this side of the story. But even before the kids emerged from hiding, the action in this second silo was really grinding along at far too slow a pace.

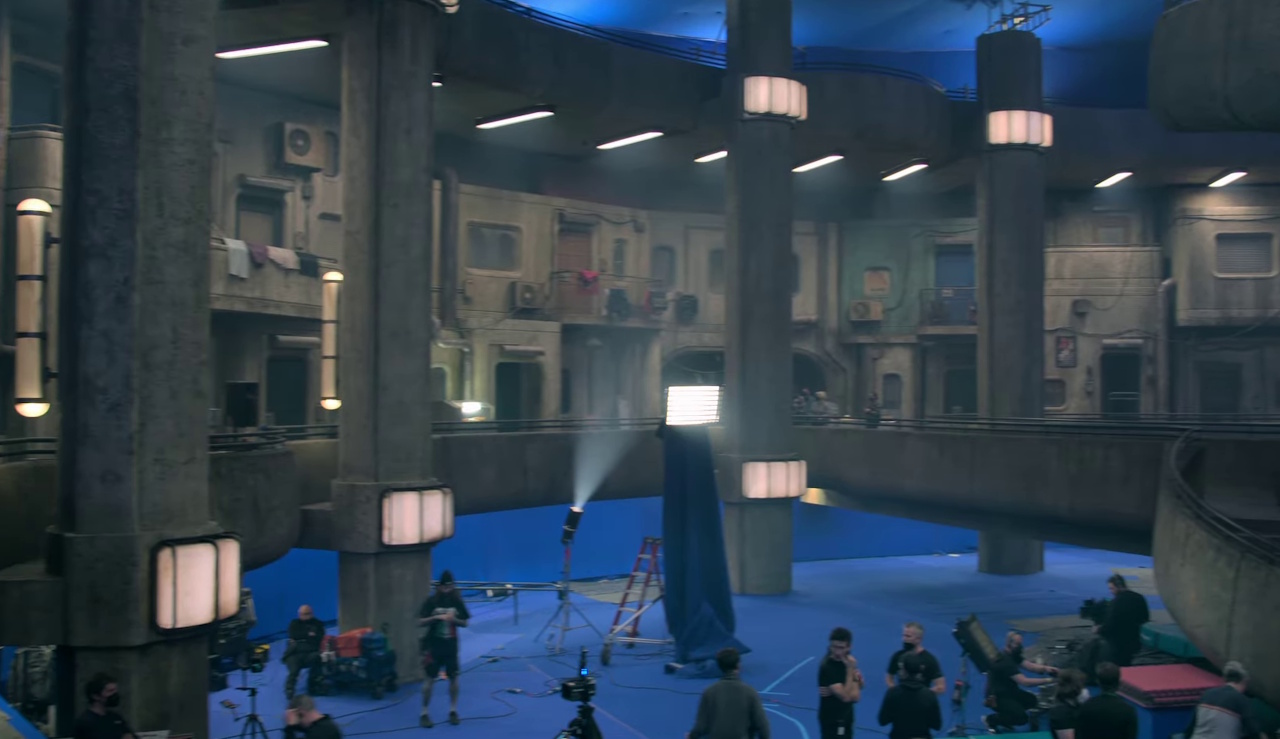

Speaking of the second silo… I’m afraid I was a tad underwhelmed by the setting, if I’m being honest. Do you know the term “bottle show?” It was originally coined in the 1960s to describe episodes of a television series made cheaply by recycling sets that have already been built, using only a handful of characters, and that are heavy on dialogue. Fans of the Star Trek franchise are very familiar with “bottle shows,” and parts of this side of Silo felt, to me, just like that. The sets were redressed to add vines and other obvious symptoms of decay, but they were otherwise identical… and for such an expensive series (Silo reportedly costs $30-$40 million per episode) the end result felt pretty cheap.

In-universe, there’s a good reason for silos looking identical. Or at least, I assume there is. But watching the show as a viewer… the fact that Juliette escaped one silo only to land in another, basically-identical silo didn’t quite sit right. And while the second silo did a good job of conveying how wrong things could go and what the stakes were for Juliette’s friends if she couldn’t fix the mistake she inadvertently made, the visuals most of the time were unimpressive. The only exception were this silo’s flooded levels, which were genuinely interesting to see – not to mention tense!

As I said at the beginning: this is the middle of Silo’s story. There are two seasons to come after this, and if the characters we met in the second silo feature in a big way, getting more development in the process, it’s not impossible to think we could revisit their introductions and look upon it a bit more kindly. But despite a wonderful performance from Rebecca Ferguson, I felt she was hampered rather than helped by the writing and the way her side of the story was structured in Season 2.

Juliette’s evolving relationship with Solo definitely had its moments, though. Solo losing his temper and shouting at Juliette – and her cowering, afraid to look at him – definitely had uncomfortable echoes of real-world abusive relationships, as did his decision to hold her captive by denying her access to her suit. This metaphor was, perhaps, a little deeper, but it was there. Solo’s childishness masked that side of his character, but he can be quick to anger and manipulative. There was definitely an uncomfortable side to him – even if it was understandable how the traumatic life he’d led might’ve left him in that position.

We need to hop over to the original silo, though! That was the side of the story that I found much more engaging.

On the lower levels, there were double-crosses, triple-crosses, and multiple characters all working toward different ends to fit different agendas. No one – not even Bernard, spying from up top – knew everything, and that left Silo to be a truly engaging series. Even when Juliette’s story seemed to be spinning its wheels or distracted with another side-quest, there were fun characters and mysteries back in the original silo to keep the show on the rails.

I have to be honest: going into Season 1 in 2023, I really did not expect much from Common. I’d seen him in Hell on Wheels – a series starring Strange New Worlds’ Anson Mount – a few years ago, but many musicians try their hand at acting and don’t really leave much of an impression. I was pleasantly surprised with his performance in Season 1 as the scheming Robert Sims, and Common excelled again in Season 2. Sims’ story expanded to include his wife this time, and they worked exceptionally well together as they tried to play both sides of the burgeoning rebellion to try to elevate their position in the silo’s heirachy.

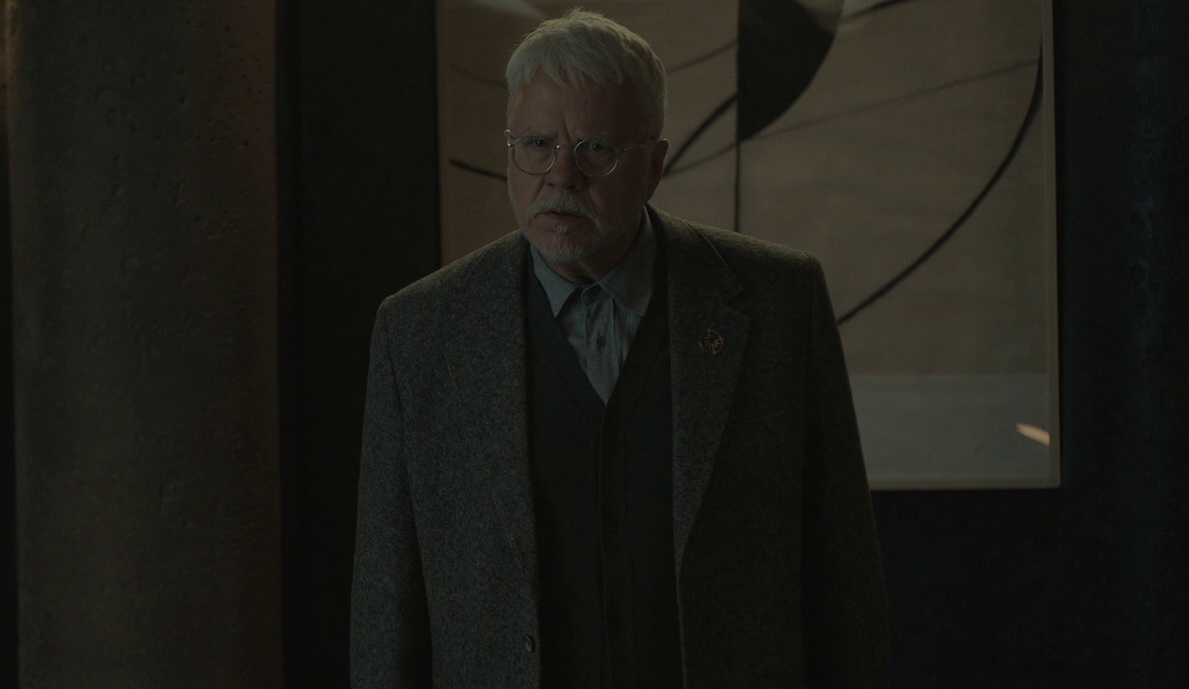

Sims turned out to have more nuance in Season 2 than he did last time. After trying repeatedly to convince Bernard to let him in on the secrets of the silo and being spurned every time, ultimately being consigned to the important-sounding but powerless role of judge, Sims began scheming more overtly. The final rug-pull that it would be Camille, not Robert, who would be let in on the silo’s secrets by its AI controller… that was a fun and genuinely unexpected twist.

Unlike Juliette’s disconnected sequence of objectives in the second silo, Bernard and Lukas’ attempts to figure out the mysterious code unfolded in a much more natural-feeling way. I can see some folks making similar criticisms as I did of Juliette’s story, because Lukas seemed to run into several dead ends before progressing. But this code-breaking story – and the subsequent revelation of the hidden vault with its library and advanced computers – felt a lot more interesting, and I was much more engaged with both Lukas as a character and the consequences of this storyline.

Knox, Shirley, and Walker made for a fun trio – and the additions of both Sheriff Billings and Dr Nichols (Juliette’s father) added a lot to the character dynamics on this side of the story. The only criticism I have, really, is that I never bought Walker’s fake betrayal of her friends, seeming to sell them out to Bernard in exchange for Carla’s safety. I had in my notes words to the effect of “this doesn’t feel like a realistic turn for her character,” so the ultimate reveal that she was double-double-crossing Bernard wasn’t as big as perhaps Silo’s writers wanted it to be. There was still a very real sense that the story could’ve gone the other way… but all that would’ve done is spoiled her characterisation! In that sense it was still a twist, but one that wasn’t built on the strongest foundations.

So Silo leaves us on a cliffhanger! What will happen to Juliette and Bernard – and will Juliette’s firefighter suit prove to be the difference in that burning decontamination chamber? What did the AI say to Lukas, and why did Bernard react by falling into such a depression? If Meadows was given the same information, why did she not communicate it to Bernard all those years ago? And what will become of the rebels – will some still try to break out, even after Juliette’s message?

Season 3 better hurry up and get here, that’s all I can say!

Seasons 3 and 4 are actually already in production; filming began in October, and both seasons will be produced back-to-back. I haven’t read the novel series that Silo is based on, but apparently there will be longer flashback sequences to the congressman and reporter we met in the Season 2 epilogue. I’m certainly curious to find out who they are and what their connection is to the silo.

I stand by what I said at the beginning: Silo’s second season had one incredibly strong and entertaining storyline… and one noticeably weaker one. I hope that Seasons 3 and 4 can do more with the second silo and the characters we met there; it might re-frame my thoughts on the way they were introduced and their arcs this time. However… part of me also hopes that, now Juliette is back, there won’t be a need to revisit these less-interesting characters or waste as much time on them going forward.

Silo continues to be mysterious, and I really can’t predict what’s gonna happen next. Bernard hinted at knowing more – he claims to know who is responsible for building the silo, but not why. And whatever Lukas told him in the final episode seems to have utterly destroyed his faith in the project – so what could that mean for the world outside? Is the entire world toxic, or – as Solo and Juliette seemed to be on the verge of discovering – is something within the silo itself poisoning the air in its immediate vicinity, trapping people inside? If so… why? What purpose could that serve? The fact that I have so many questions that I want answered is, quite frankly, an indication of how invested in the story I am and how much of a good time I’m having!

So that was Silo Season 2.

I really can’t wait to find out what’s coming next – and I hope we’ll see Season 3 within the next twelve months or so. Some made-for-streaming shows take a long time in between seasons, but with production on the next chapter of Silo already well underway, I think there’s hope that we might see it at the tail end of 2025 or early in 2026. I’ll be keeping my fingers crossed, anyway.

When Season 3 premieres, I’ll do my best to review it here on the website – so I hope you’ll stay tuned for that. Silo was my favourite TV series of 2023… will its second season repeat that feat this year? There’s still a long way to go and a lot of exciting TV coming our way, but if you swing by in late December, you’ll find out.

Silo Seasons 1 and 2 are available to stream now on Apple TV+. Silo is the copyright of Apple Studios, AMC, and Apple TV+. This review contains the thoughts and opinions of one person only and is not intended to cause any offence.