Spoiler Warning: There are spoilers ahead for Shenmue.

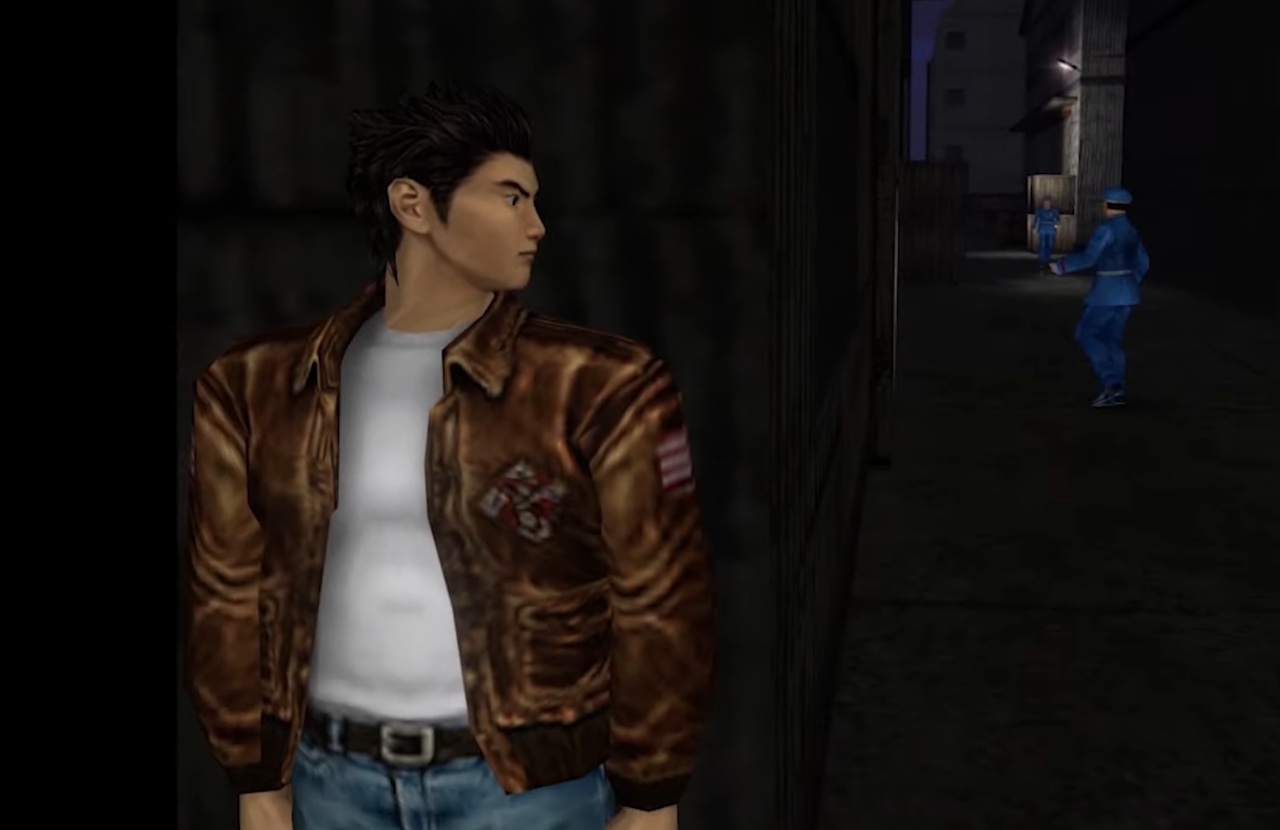

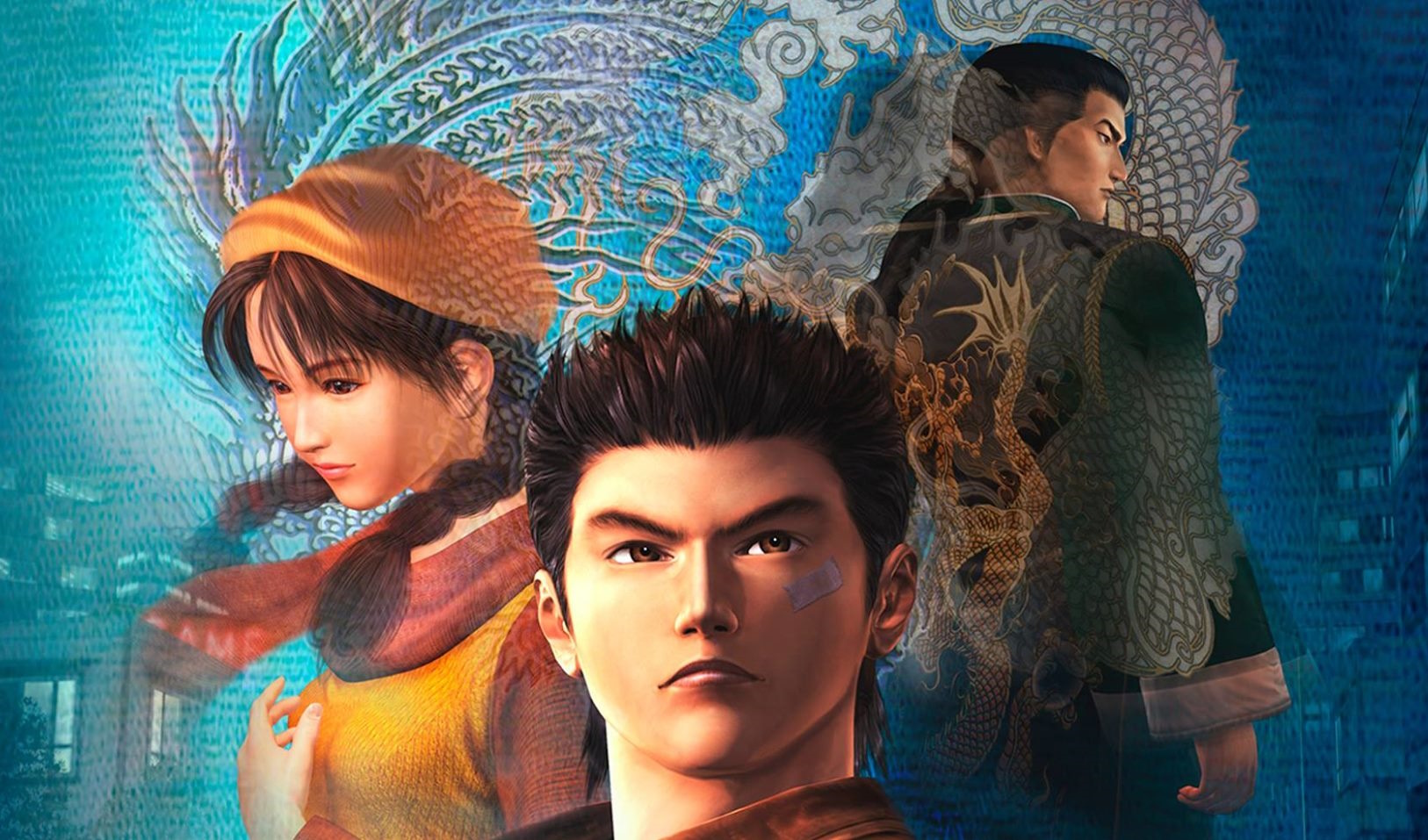

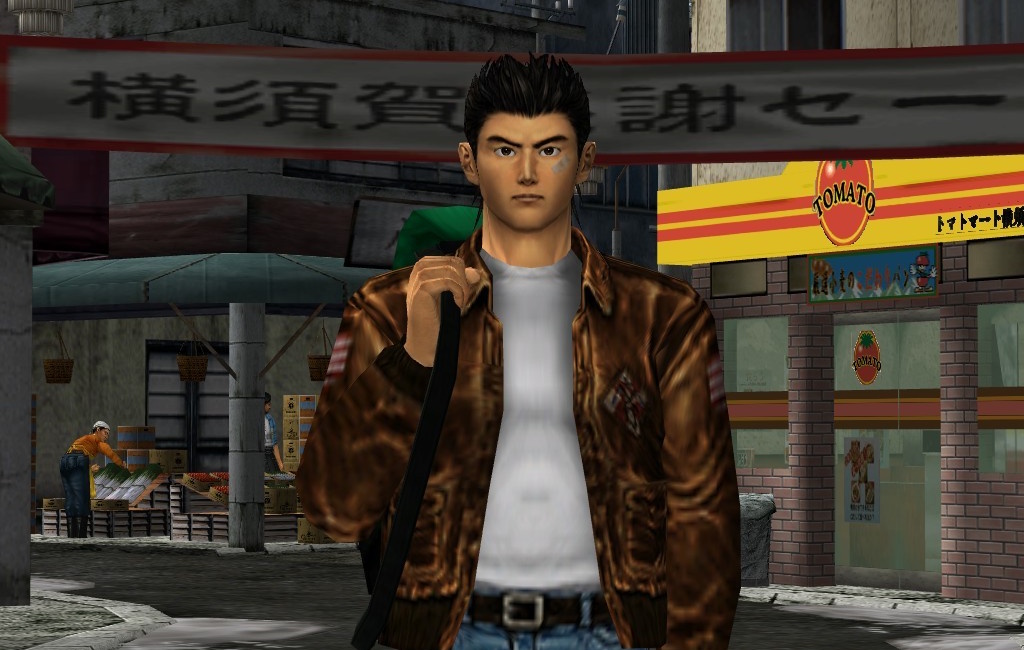

This year is all about Shenmue’s 25th anniversary! A little while ago, I wrote up my reflections of the game to mark the anniversary of its launch in Japan, but I find myself with more to say about this landmark, transformative game. So today I thought it could be a bit of fun to explore Shenmue’s game world together and visit a few of my favourite locations.

Shenmue was the first game I played that gave me a profound sense of freedom. The game’s world was open and explorable – and many buildings could be entered and investigated, too, including those that had nothing to do with the main quest. That was revolutionary twenty-five years ago, and went a long way to making Shenmue into the incredibly immersive title that it was. It wouldn’t be overstating it to say that Shenmue showed me what the future of gaming could look like in the 21st Century – and kept me playing at a time when I might’ve otherwise drifted away from the hobby.

That’s really just a summary, though, so if you want to read more about my recollections of playing Shenmue, you can find the full article by clicking or tapping here.

A couple of caveats before we go any further! Firstly, all of this is just the subjective opinion of one player. If I highlight places and locales you hate, ignore somewhere you think is important, or you just don’t like what I have to say… that’s okay. There’s a lot to love about Shenmue, and there ought to be room in the fan community for differences of opinion and polite discussion.

(2000 in North America and Europe)

Secondly, I’m only going to be looking at locations from the first Shenmue on this occasion. When Shenmue II celebrates its 25th anniversary in September next year, I’m planning to do a similar write-up of the game… and possibly another piece like this one (assuming I’m still around and assuming I remember!) So don’t worry, I haven’t forgotten about Shenmue II… but it isn’t the focus of this piece today.

Phew! With all of that out of the way, let’s get started.

Location #1:

Hazuki Residence: The Kitchen

Let’s start at home: which for Ryo is the Hazuki residence and dojo in Yamanose. There are plenty of iconic places around here – but an underrated one has to be the kitchen. In a normal house, the kitchen is usually a hub of activity; it’s where we cook, where we sit and eat, and a room we generally spend a large amount of time in. But in Shenmue – and many other similar games, to be fair – the kitchen is just… set decoration. It exists because without it, Ryo’s house would feel incomplete. But there’s not really much of a reason to spend time here, and aside from a couple of cut-scenes, the game’s story largely passes this room by.

And I think that’s what makes this room (and several of the other places on this list) so interesting to me. It’s a space where nothing happens, but it’s important for the immersion and world-building that a game like Shenmue needs. There are also a few interesting little things in the kitchen; Ryo can find a can of tuna for the kitten, for example. Cupboards and the fridge can be opened and examined, which is something that felt really immersive in 1999/2000. And it’s possible to chat with Ryo’s house-keeper/surrogate mother, Ine-san, too, as she spends a fair amount of her time in the kitchen.

Location #2:

The Harbour: Fishing Spot Behind the Lounge

The harbour is one of my favourite places in Shenmue; it’s just so atmospheric. And for someone who grew up near a working harbour, it’s also the location in the game that probably feels the most familiar – at least in some ways. Directly behind the lounge, past the steps where the homeless man sits, is one of my favourite spots in the harbour. This is an area you’ve definitely walked through and driven through, but probably haven’t spent a lot of time in! There are occasionally fishermen here, as well as an NPC with a sketchbook, but other than that, Ryo has no reason to ever stop here; it’s a connection point between other, more densely-packed or story-rich areas.

I find something peaceful and serene about this area, though – especially after dark. The view across the water shows the far side of the bay, and there’s a large warship or other vessel in the distance. But this part of the harbour doesn’t see much action – aside from the odd pedestrian or forklift during daylight hours, you’re on your own. And that makes it a peaceful, easily-overlooked spot. The world of Shenmue – which feels so rich and deep thanks to its numerous NPCs with their own schedules – simply rolls along, passing you by as you take in the sights and sounds of the harbour.

Location #3:

Dobuita: Game You Arcade

I grew up in a rural area, and where I lived there weren’t any video game arcades. I visited one a few times as a kid, when we’d visit a bigger city, but I never really had the arcade experience that many folks my age did – and I think it’s for that reason that I fell in love with Shenmue’s arcade. I’d played Hang On – or a motorcycle game similar to it, at any rate – at least once before, but Space Harrier was brand-new to me. I spent hours in the Game You arcade playing those titles, as well as the darts mini-game which was also surprisingly fun.

The arcade is compact, but beautifully detailed. The room is lit by old fluorescent lights, and the cabinets seem to glow, even from a distance. The whole thing has a very artificial feel – which, ironically, perfectly recreates this kind of environment. The arcade always has at least one other person present, yet it can feel empty and almost like a “liminal space;” the room exists to guide you to the mini-games, yet it’s a beautiful rendition of an ’80s video game arcade in its own right. It’s a very atmospheric space.

Location #4:

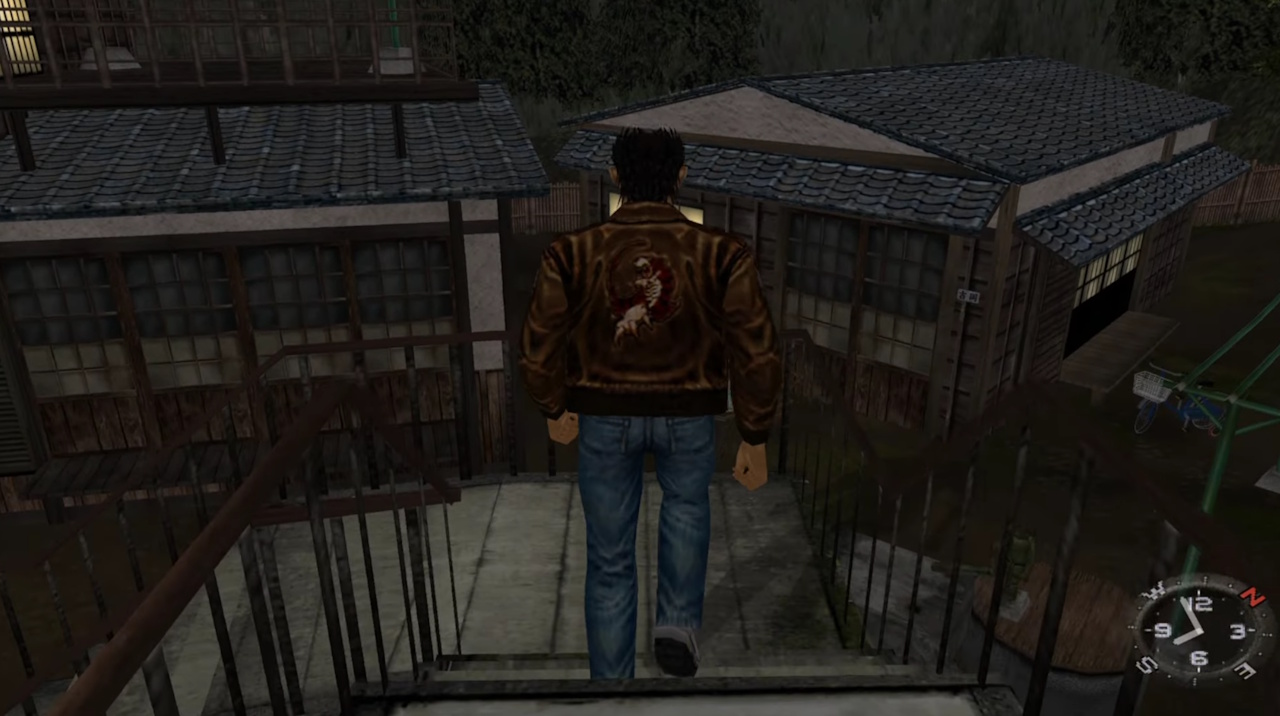

Yamanose: Down the Stairs

In Ryo’s hometown of Yamanose, there’s a flight of stairs that you’ll have passed by countless times on your adventures. But did you ever once descend those stairs to see the houses below? There’s only one reason to visit this area, and it’s easily overlooked: if you feed and pet Megumi’s kitten at the shrine, eventually it gets better and wanders off – and you can find it by one of the homes down these steps. But that side-quest is very much optional – so many players will have missed it.

For me, these houses just have a vibe to them that’s hard to put into words. They’re traditional Japanese houses, which I guess is part of it. But they help make Shenmue’s world feel lived-in and real; the people inside seem to have lives of their own, like everyone else in the game world. It would’ve been really easy for Shenmue’s developers to make this area inaccessible; set dressing for Yamanose. But you can explore this area, knock on doors, and even see the clotheslines, wheelbarrows, bicycles, and other little pieces of these people’s lives. Little details like that are what made Shenmue stand out to me when I first played it – and I always like taking a little detour to this uninteresting little corner of Yamanose.

Location #5:

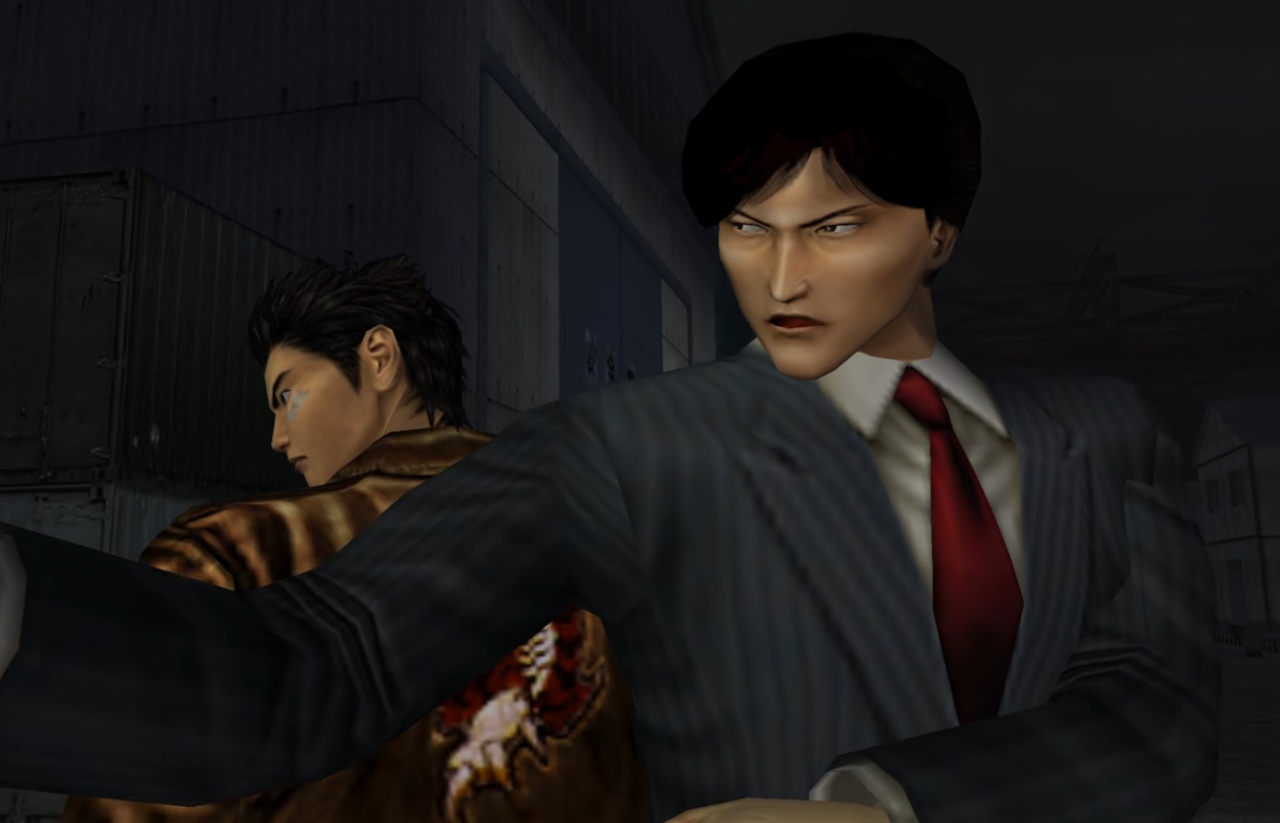

Dobuita: Nagai Industries (The Yakuza Den)

Have you ever walked into a room and instantly known you weren’t supposed to be there? That’s the feeling I get when Ryo enters Nagai Industries in Dobuita, which is a Yakuza den masquerading as a legitimate business. That feeling is really hard to pull off in any form of media, and Shenmue absolutely nails it here. Ryo can be directed to Nagai Industries as part of his quest to find “men with tattoos,” but it isn’t an essential part of the story and it can be accessed at other times, too.

The conversation Ryo can have with the obviously shady man inside made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up the first time I accidentally triggered it – it’s so well-written. Even if you do find yourself going here as part of Ryo’s quest, you won’t spend long in the building – yet it’s a unique space in the game’s world. Ryo does get mixed up with a gang later on in the story… but it isn’t this gang. These criminals are just doing their own thing, and Ryo can wander into their office almost at random. It’s a strange interaction – and a fun place to visit.

Location #6:

The Harbour: Harbour Lounge

There’s a strange kind of beauty in urban decay… at least, sometimes there is. The harbour lounge feels like a well-used space that’s in need of a new coat of paint and a bit of TLC, and that’s exactly the kind of vibe that the developers wanted to convey. The paint on the walls is chipped and peeling, the leather seats have seen better days, and I just get the sense that the lounge is a heavily-trafficked space, probably bustling with sailors, harbour workers, ferry passengers, and the like. The soundscape for this area has inaudible conversation chatter playing, too.

Which makes it all the more eerie that the harbour lounge is usually all but deserted. Aside from the small shop counter in one corner, which is always staffed, the harbour lounge is usually empty. At most, you might encounter one or two people in here. Again, it’s giving me “liminal space” vibes; there’s an almost otherworldly feel to a place that should be packed with people – and has all the evidence of being well-used – yet is often empty.

Location #7:

Dobuita: Yamaji Soba Noodles

The owners of Yamaji Soba Noodles clearly know Ryo, and one of the people Ryo needs to speak to on his quest is a regular patron. But there’s no reason to set foot in this noodle parlour… other than for the fun of exploring Dobuita and Shenmue’s game world. In 1999, no one knew what the term “open world” would come to mean, but to me, a shop like Yamaji Soba Noodles in Shenmue perfectly encapsulates the open world idea. It’s the kind of place that needs to exist in a real town; the denizens of Dobuita need places to eat. But from a gameplay perspective, it doesn’t have a purpose. It’s the kind of place that was created for the sole purpose of adding depth to Shenmue’s world… and I really admire that.

The noodle shop itself is compact with a bar area for patrons to sit, and behind the counter the owner can be seen working away. A member of the restaurant’s staff can be encountered out in Dobuita, and you can even find his apartment elsewhere on Dobuita Street. You can’t go inside… but again, this adds so much depth to the game world and makes these NPCs feel real in a way some open world games struggle with even today.

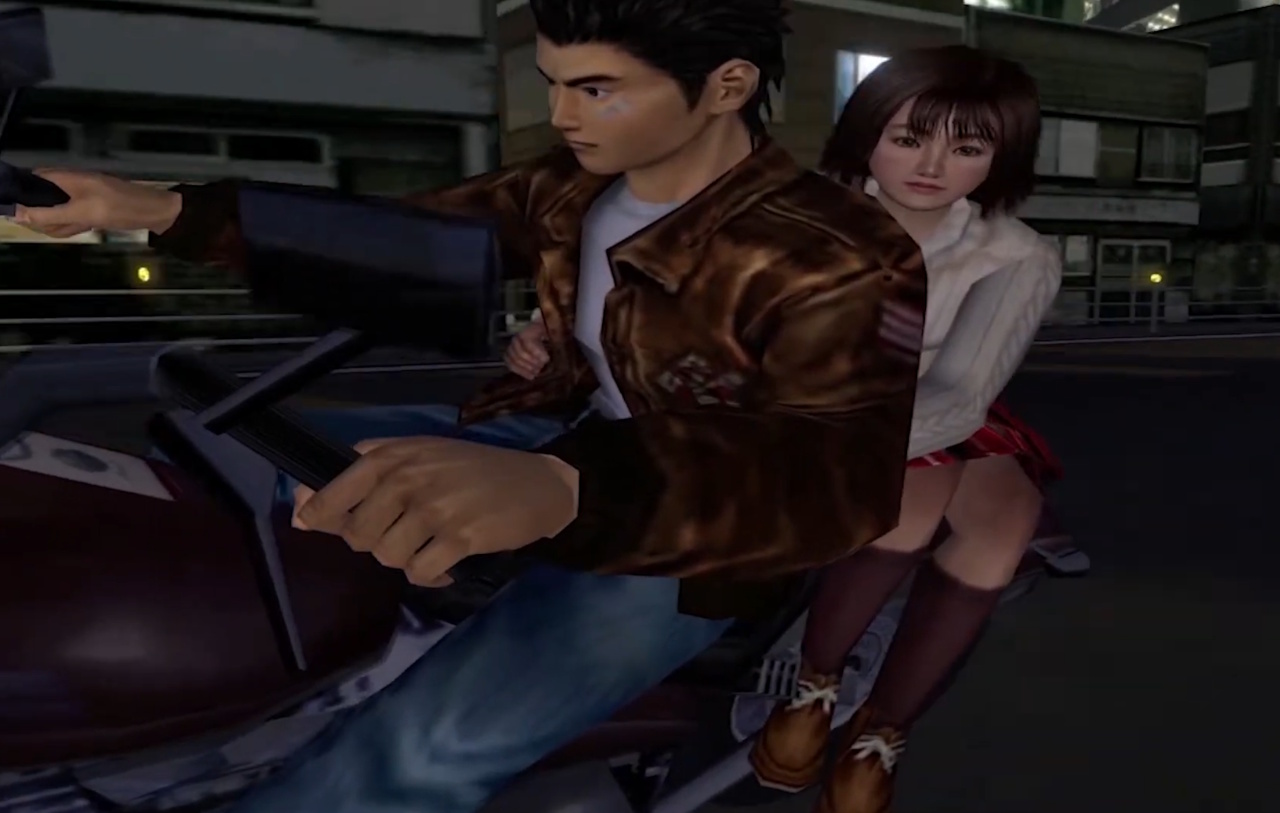

Location #8:

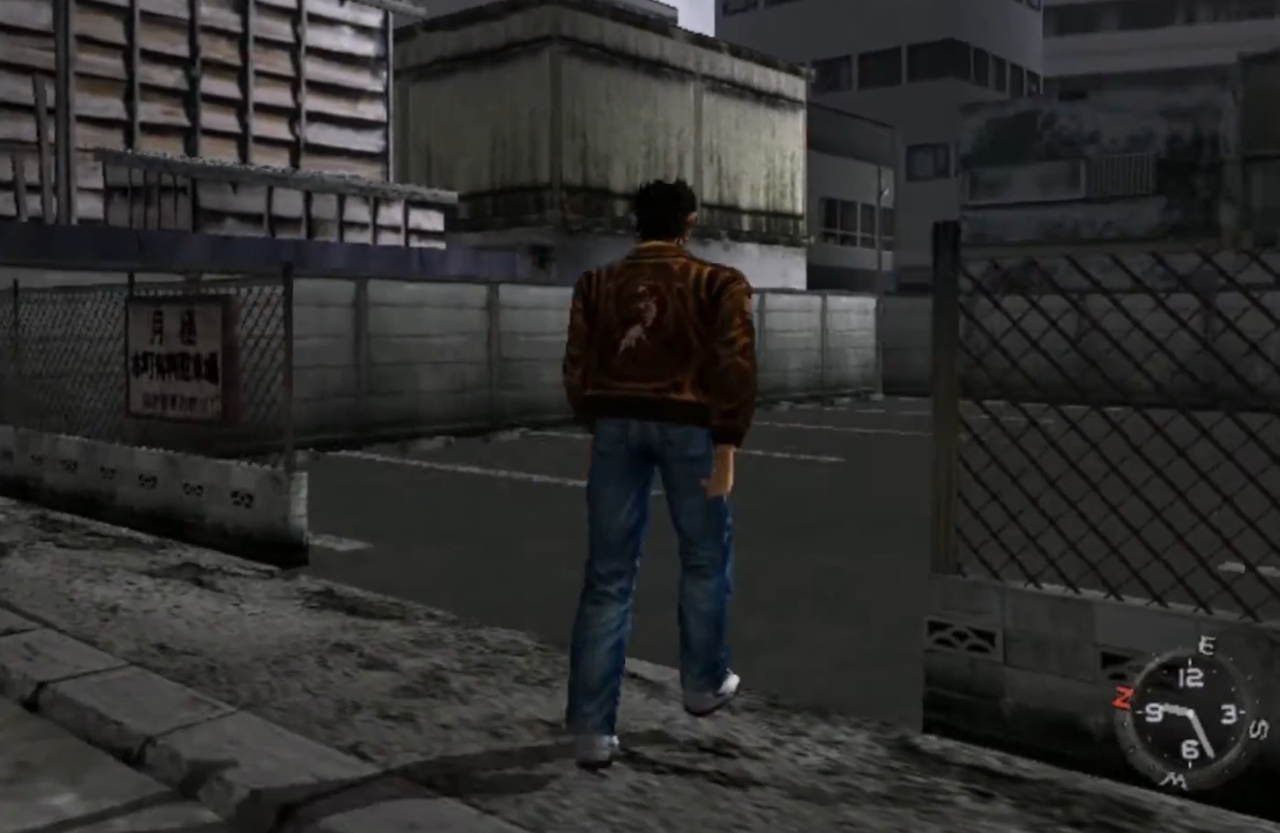

Dobuita: Car Park

The car park near the end of Dobuita Street has an in-game function: it’s one of only a few places where Ryo can practice his moves in between fights. But I think it’s also worth acknowledging the area on its own merit – it’s more than just an empty arena to throw kicks and punches around! There are no cars on Dobuita Street – but there are plenty on the main road just beyond. The car park is, therefore, a space for both residents and visitors to leave their vehicles before venturing out on foot.

I’d never paid any attention to a car park in a video game before. I’m sure titles like Grand Theft Auto had car parks in their game worlds, but because of how rich and detailed Shenmue was, I felt compelled to explore this space more than I ever had before. The way it was integrated into the game, too, worked really well – and it quickly became my favourite place to practice Ryo’s martial arts moves.

Location #9:

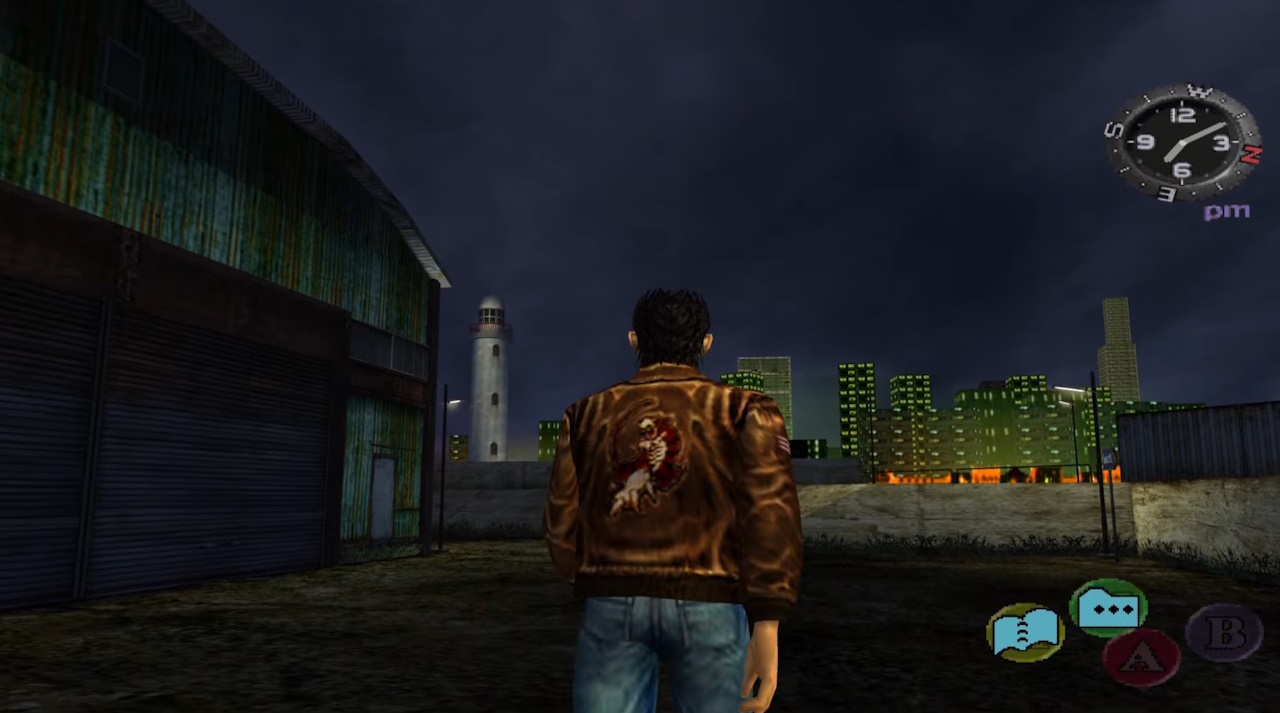

The Harbour: Old Warehouse #8

Nobody likes mandatory stealth sections in games… especially mandatory stealth sections in old games with janky controls and awkward AI. But once you get past the “sneaking in” portion, Old Warehouse #8 – home of Master Chen and Guizhang – is a really interesting place to be. Most of the time you’ll spend here comes in cut-scene form, but if you take a break from the story and just visit the warehouse, there’s a lot to see. It has a quiet, understated feel that contrasts with the bustling harbour outside.

I like antiques, and the warehouse isn’t the only place in Shenmue to find old and interesting artefacts! But there’s something special about walking around the warehouse, looking at some of the items on display. It’s an interesting place to spend a little time, and one that’s easily overlooked.

Location #10:

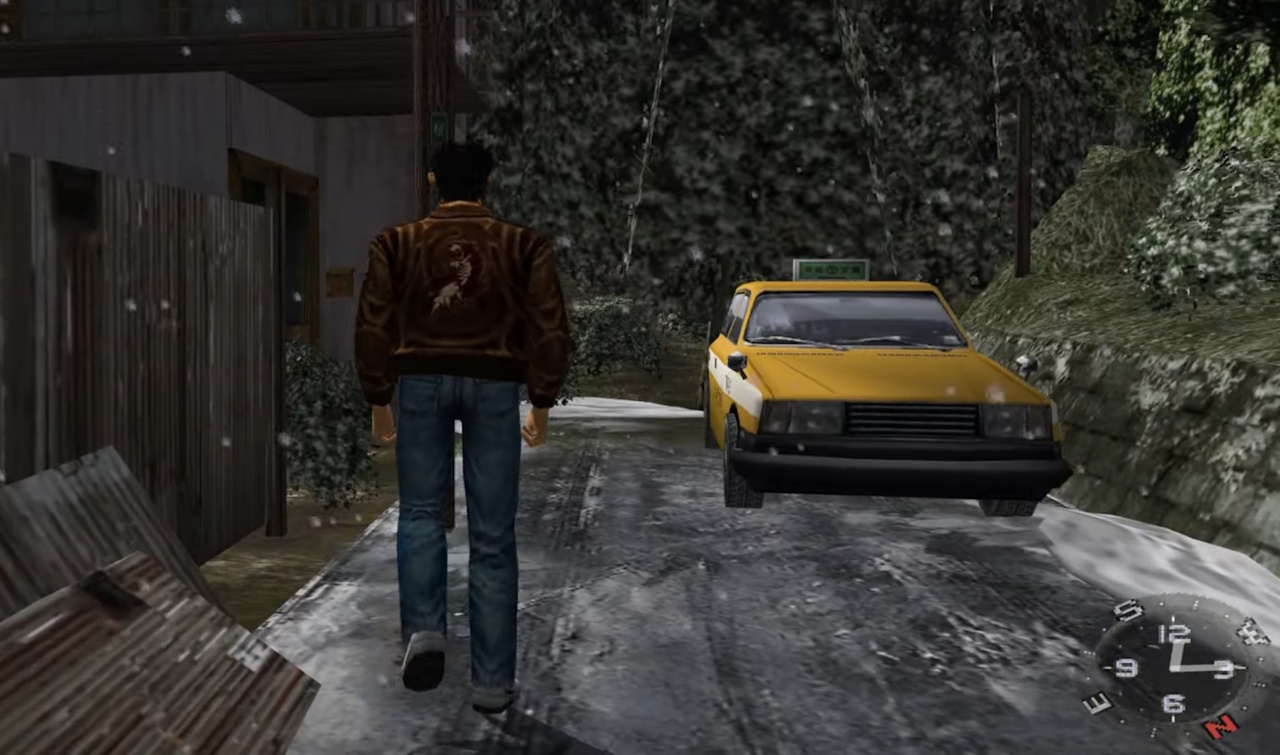

Sakuragaoka: The Taxi Cab

At the end of the road in Sakuragaoka, past the park, you can find a taxi cab. Ryo can’t take a taxi anywhere, and because it’s located beyond both the park and any houses in Sakuragaoka that you might want to visit… there’s really no need to come here. But the taxi is interesting; it feels like more than just set dressing. There’s a man – Nomura-san – who Ryo can speak to who drives the taxi, and he clearly knows Ryo and will tell him a little about his life. Nomura-san can also be encountered in Dobuita, as well as seen tending to his taxi.

Walking beyond the “edge” of a game world can often feel empty; the world stops where the developers say it stops. But Shenmue has content beyond the edge of where its story takes place – there’s no reason to come here or talk to the taxi driver other than “because they’re there,” and I really love that about the game. Standing here, at the end of the street, doesn’t feel like the edge of a video game level with an invisible wall… it feels like a road with a taxi parked on it.

So that’s it.

We’ve taken a look at some of my favourite places in Shenmue… places that, maybe, you wouldn’t have expected to see on a list like this!

I wanted to convey just how immersive and interesting Shenmue’s world was twenty-five years ago… and still is today. Even in the smaller places, and areas with no storylines or quests, there are still interesting things to see, NPCs to talk to, and ways to soak in the atmosphere of this incredible game. Shenmue pioneered open-world designs and features that titles today are still striving for – and many modern games either miss out or don’t get right. It really is a landmark title, and one that I wish more people had paid attention to back in the day!

So I hope this has been something a bit different. I was inspired by a couple of YouTube channels: Wandering Through Shenmue, whose channel I encountered while looking for screenshots of specific locations in the game world when writing a couple of my other articles about Shenmue, and Any Austin, whose video essays on video game levels and designs are genuinely interesting. I hope you’ll check out both of those channels if you have time.

If you missed my piece celebrating Shenmue’s twenty-fifth anniversary, you can find it by clicking or tapping here. And if you want to check out my thoughts on whether the Shenmue saga might have a future in light of some recent news, you can find that by clicking or tapping here.

I honestly can’t believe that it’s been twenty-five years – a quarter of a century – since Shenmue launched. At any rate, I hope revisiting some of these locations with me was a bit of fun!

Shenmue I & II and Shenmue III are available now for PlayStation 4 and PC. Some images, promo artwork, and screenshots courtesy of Wandering Through Shenmue on YouTube and Shenmue Dojo. This article contains the thoughts and opinions of one person only and is not intended to cause any offence.