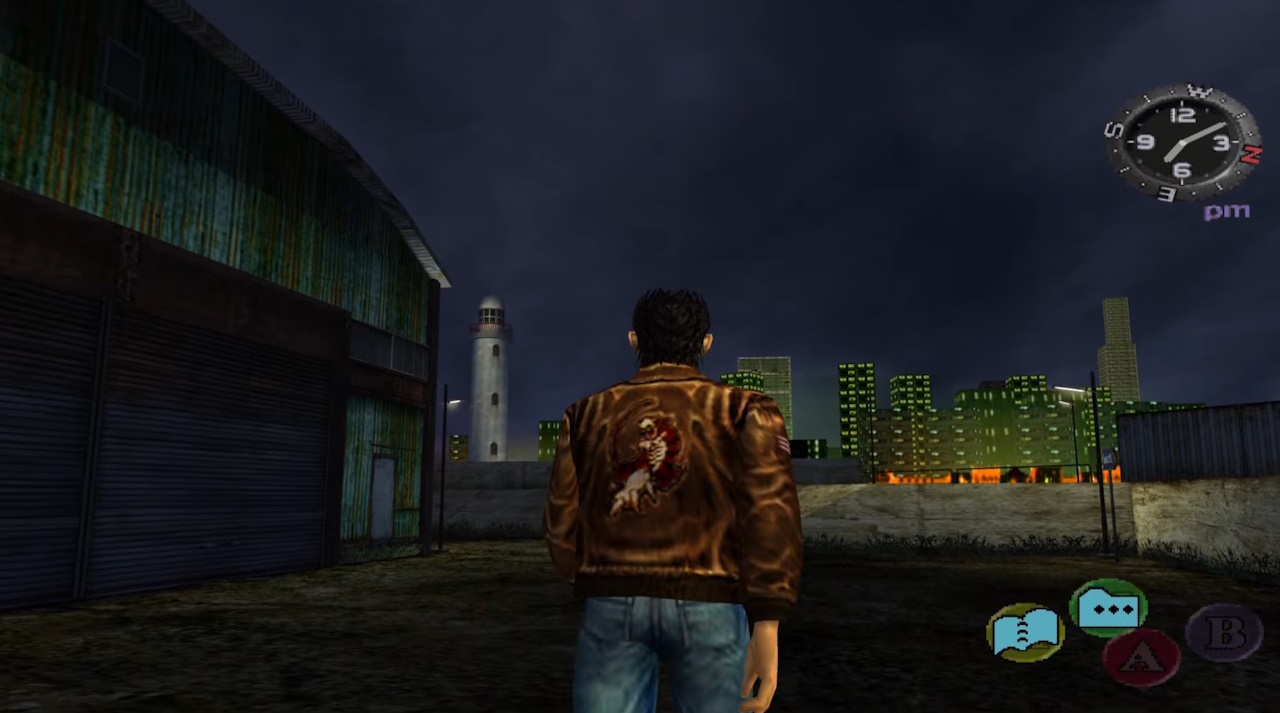

Spoiler Warning: Beware minor spoilers for Shenmue and Shenmue II.

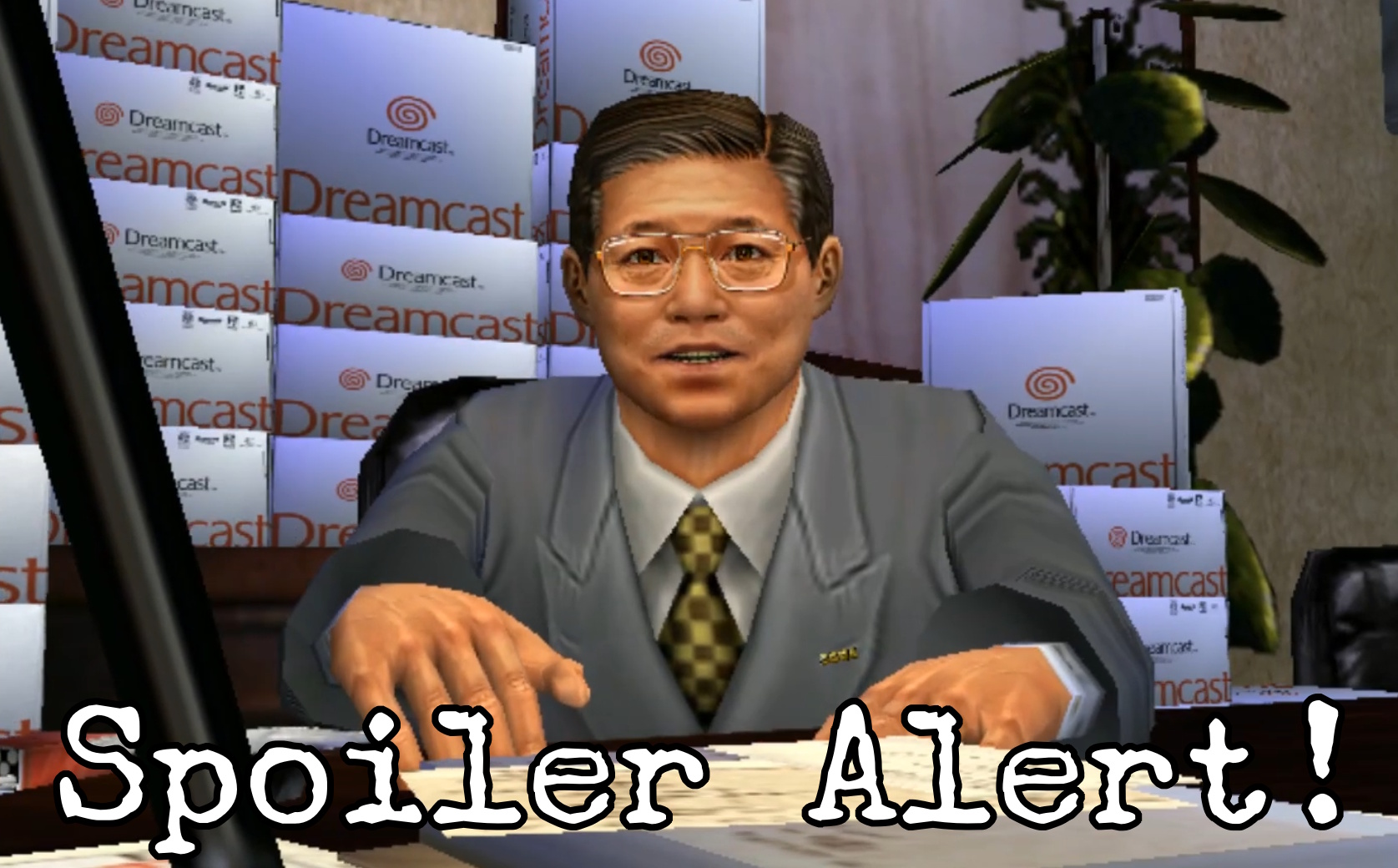

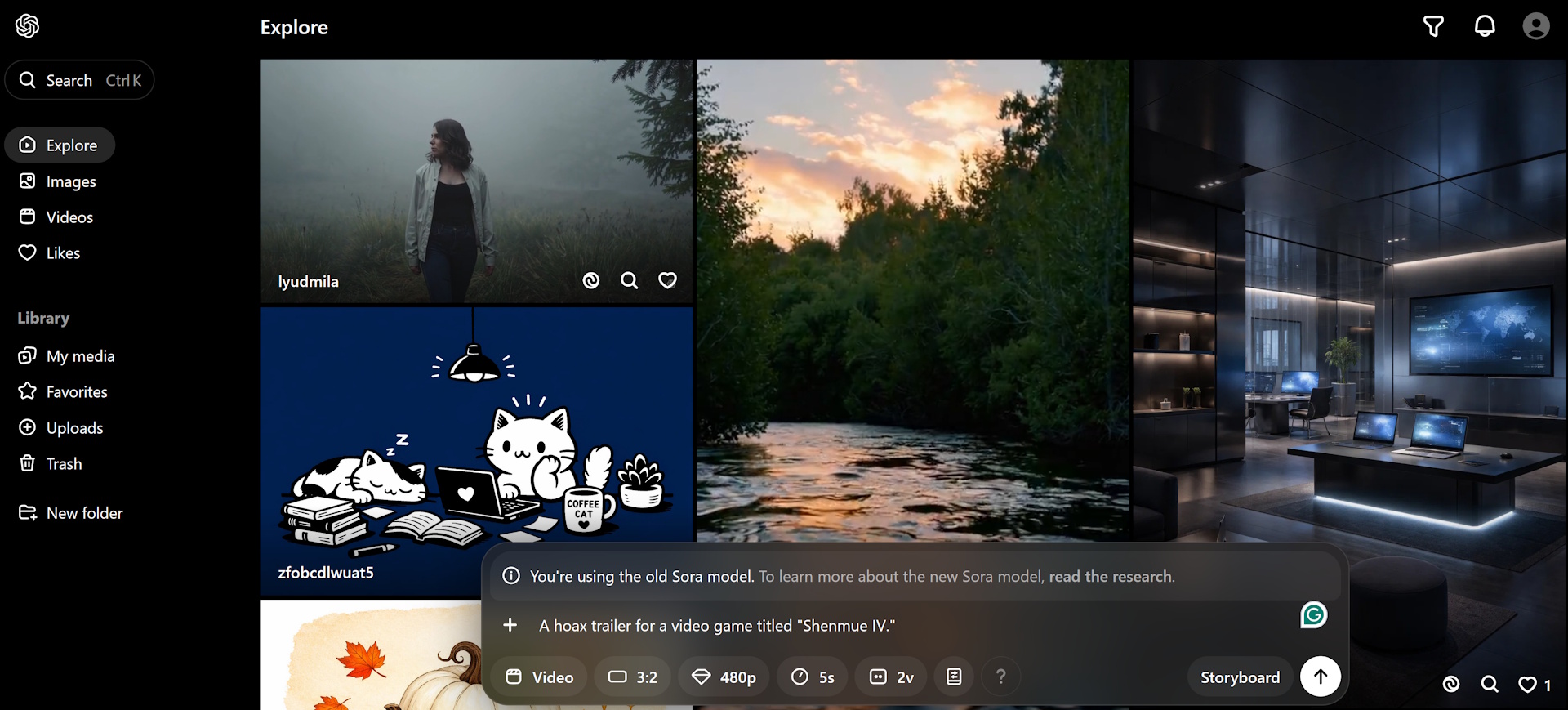

I started to write this piece in December, when the (pretty obviously fake) “Shenmue IV” trailer started doing the rounds online, but everything I wanted to say back then pretty quickly became irrelevant after just a few days, when both YSNet and the trailer’s creator confirmed that it was a hoax. But the fake trailer for a potential sequel to 2019’s Shenmue III did, for a brief moment, raise some hopes in the fan community, so I wanted to talk a little about the series’ future today.

First of all, I have absolutely no problem with fans creating mock-ups of games, movies, or TV shows that they’d like to see. And I don’t really mind the use of generative A.I. by fans for such projects, either. A.I. is a contentious subject, but fans making things they’re passionate about in a totally unpaid, non-commercial way is, in my view, a far better use of generative A.I. than a massive corporation using it to cheap out and even lay off staff.

But – and you knew a “but” had to be coming after all of that – I have absolutely no time for hoaxes, fake “leaks,” and lies, which is what this fake trailer was. There’s no excusing that, in my opinion, and lying to fans of a dormant (or dead) series that a sequel is coming is just… cruel. The hoaxer claims to have done it out of passion for the Shenmue series, but I really struggle to see it that way. Although the fake trailer didn’t convince me it was real (we’ll talk more about that in a moment), it clearly did trip up a lot of fans. When the community has had so little by way of good news in such a long time, there’s absolutely no excuse for this kind of thing. This was a prank that, whatever the intention may have been, caused hurt and disappointment – and any human with a brain cell and basic empathy would have known that before releasing something like this.

The trailer itself raised a ton of red flags for me, but it was pretty competently-made. It’s pretty neat, in some ways, to see what generative A.I. can do already, and I can’t help but wonder if, one day, the same kinds of tools used to create this hoax may have a role to play in telling the final chapters of the Shenmue saga.

So… why didn’t the hoax convince me, then? The answer has less to do with the content of the trailer itself and more to do with what we know of YSNet, Sega, Shenmue III, and the state of the series at this point in time. In a word, Shenmue III was a flop. It barely broke even, despite raising a ton of money via Kickstarter, and YSNet has since worked on a couple of smaller games: Air Twister and Steel Paws. Steel Paws only launched in 2025, and YSNet is not a big studio. So… when were they supposed to have worked on Shenmue IV? Neither game blew up, either, making Yu Suzuki and his team the kind of money they’d need to fund development on a bigger title like Shenmue IV.

That knowledge alone convinced me that the trailer couldn’t be real before I’d even seen a single frame. I watched the trailer a couple of times, though, more out of curiosity than anything else, and while nothing in the trailer itself leapt out at me and screamed “hoax,” I was still confident that it would be revealed to be fake before too long. As it happened, I think YSNet put out a statement within just three or four days, pretty much as soon as they were made aware of the situation. The hoaxer confessed and explained their reasoning shortly thereafter.

I was a huge Shenmue fan back in the Dreamcast days, and I was left pretty disappointed when the series was abandoned and couldn’t be concluded. But, as you may know if you’re a regular around here, I didn’t pick up Shenmue III when that game eventually launched back in 2019. Why? Well, it’s simple – in my view, the game had *one* job: finish the story and bring the saga to an end. When it became clear that Shenmue III wasn’t going to do that, I genuinely couldn’t believe it. The idea that the game would either be a massive hit or that YSNet – which, by that point, had burned bridges with the fan community through things like a deal with the Epic Games Store on PC – would be able to launch another multi-million-dollar crowdfunding campaign just seemed impossible. If Shenmue III wasn’t gonna finish the story in 2019, then the story would never be finished. That was my belief at the time, and that’s why I didn’t buy Shenmue III.

And… am I wrong about that?

Shenmue III’s low sales were predictable. The port of the first two games didn’t sell well on PC or PlayStation 4 in 2018, and we’re talking about the sequel to a barely-remembered game on a platform hardly anyone bought. Did anyone expect Shenmue III to be “Game of the Year” in 2019? Really? On a crowdfunding budget?

Look, it’s a miracle that the latent Shenmue fan community was able to raise so much money to fund the development of a third game in the 2010s. And I know I don’t speak for anyone but myself, but surely there was an expectation that Shenmue III would bring the story to an end. That would have been a request so blindingly obvious that I wouldn’t have even stated it when the crowdfunding campaign was underway. But, for reasons that I still cannot fathom a decade later, Yu Suzuki was unwilling to make cuts to the game’s story, and genuinely believed Shenmue III would be a big enough hit that he’d be able to go on and make a fourth, fifth, or even sixth title. Would kids these days call that “delulu”?

The lack of any real news about Shenmue since the third game and the single season of the animated series really just proves that I was right, in 2019, to take the stance that I did. And although this hoax may have stirred the pot… I don’t think it’s really helped Shenmue IV’s cause as much as some folks seem to think.

Let me explain what I mean.

On YouTube, the fake trailer got just over 32,000 views in December. And it’s by far the most-viewed video on the subject of Shenmue in a while. But those really aren’t high numbers if you’re talking about launching a game that’s gonna take several years to develop.

Why was Shenmue never picked up in the 2000s? Why was Sega so keen to part with the rights to the series in the 2010s? Why did Shenmue III barely break even? And why was the anime cancelled after just one season? The answer is the same: there just isn’t enough of an audience for this story.

That’s why I was beyond disappointed when Shenmue III didn’t conclude the saga. Because I knew, even then, that getting another shot would be nigh-on impossible. Because I knew that, as loud and enthusiastic as some Shenmue fans can be, we’re a tiny – and, to be blunt about it, a shrinking – number. Because I knew that, when the game inevitably didn’t take off and didn’t attract a huge new audience, the chances of a sequel were basically nil.

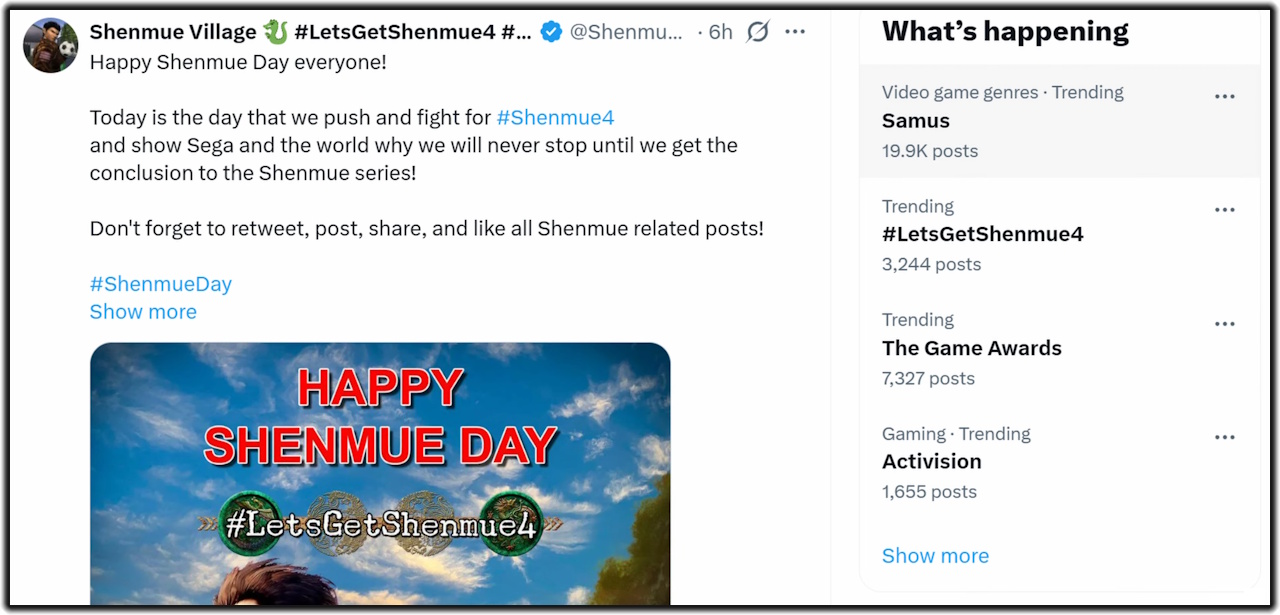

And that’s why the hoax was especially cruel. The Shenmue fan community does what it can to keep the games in the public consciousness. Stunts like renting a billboard in New York or getting a hashtag trending on Twitter are all designed to provoke a reaction from the likes of Sega, YSNet, and anyone who might potentially have money to invest in a new game. And it’s great to see, more than a quarter of a century later, that these fantastic titles can still elicit such strong emotions. But I can’t shake the feeling that fans are just… shouting into the void.

Gaming the system to force a hashtag to trend, or encouraging the fandom to vote, en masse, for Shenmue in online polls can only go so far. And even these successes are muted – the hashtag may trend on Twitter, if everyone posts it at the exact same moment, but that’s just a quirk of how Twitter works. A few thousand tweets is all the community can muster, even under the best circumstances. And even then, it has to be a carefully-coordinated campaign; it isn’t an organic movement of people discussing this series and its future unprompted. And YSNet, Sega, ININ Games, and everyone else involved? They realise that.

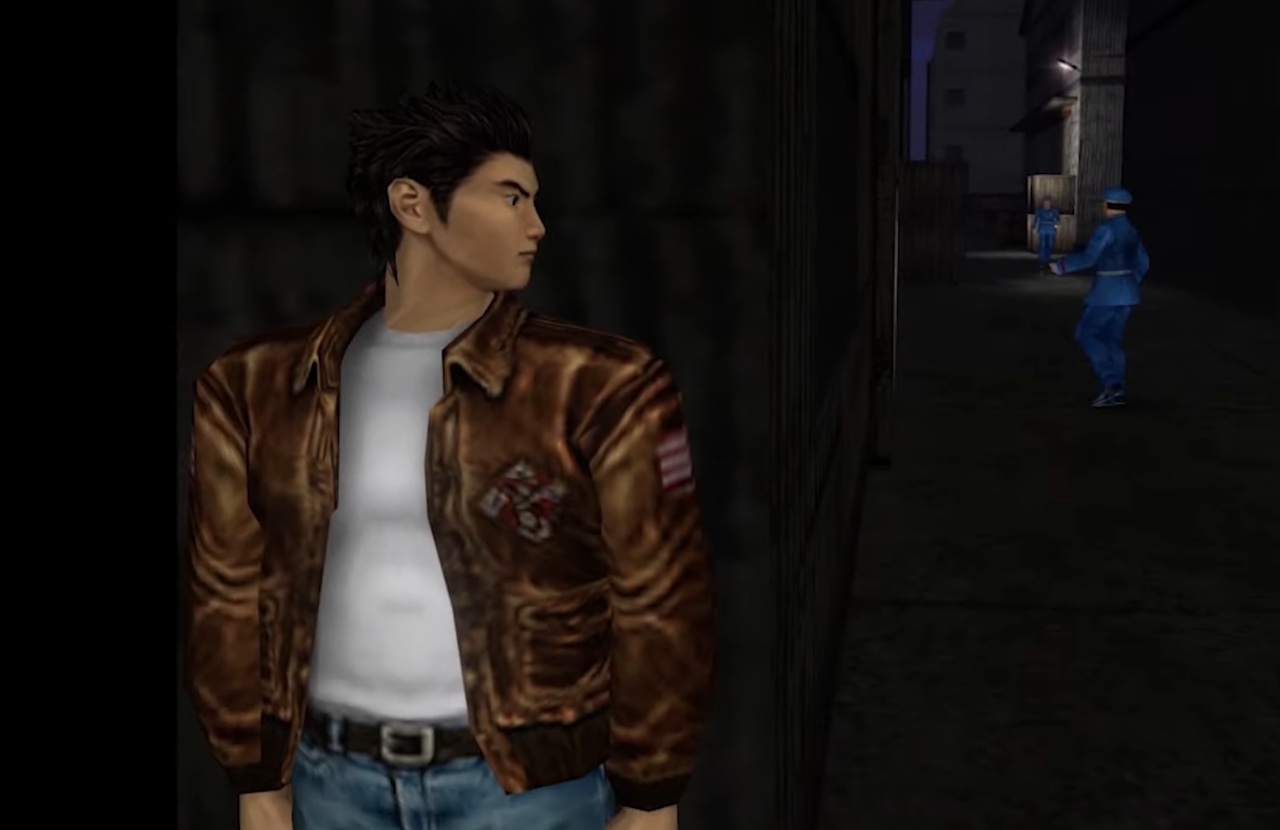

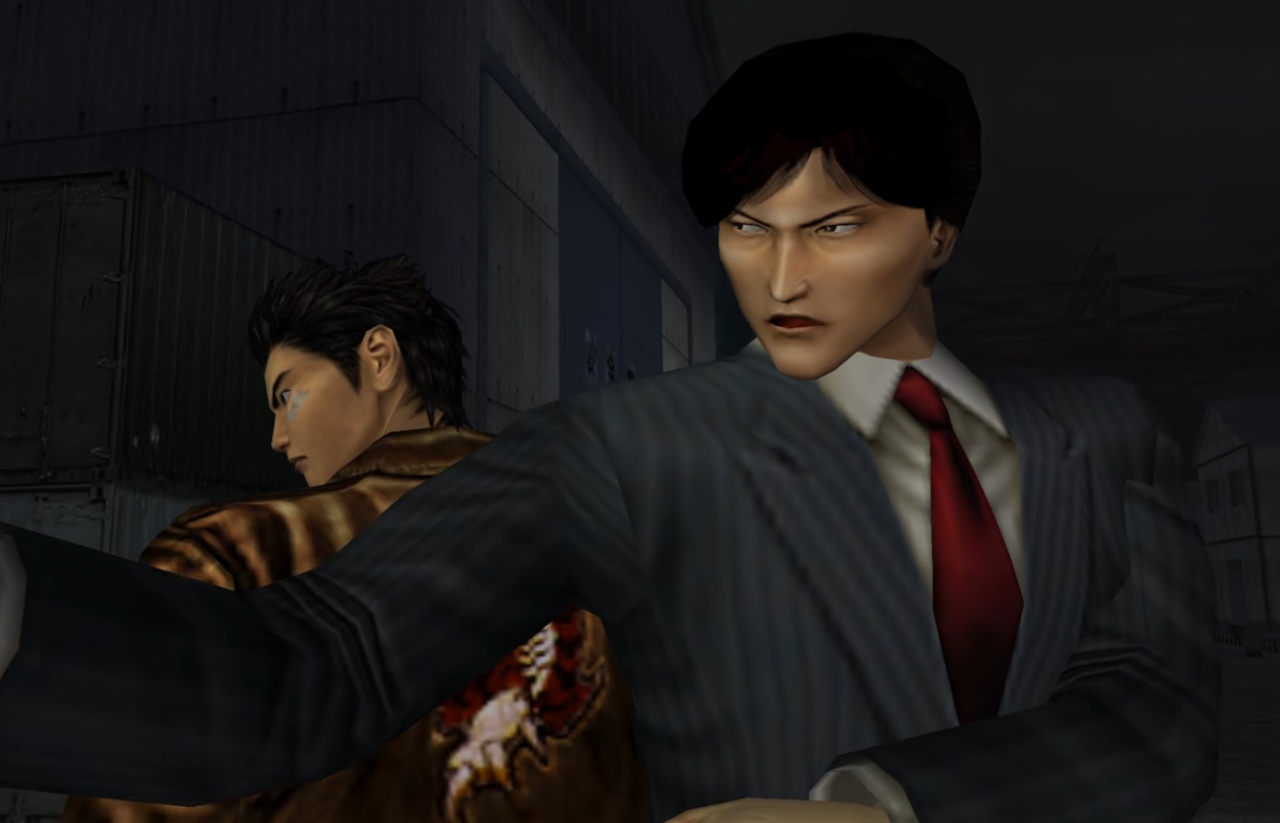

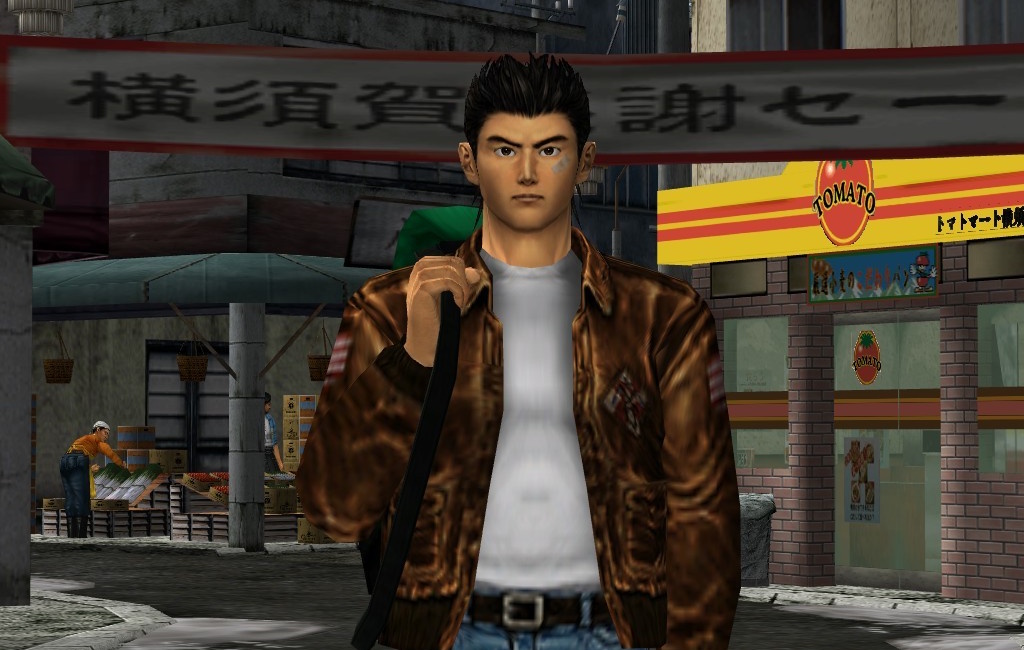

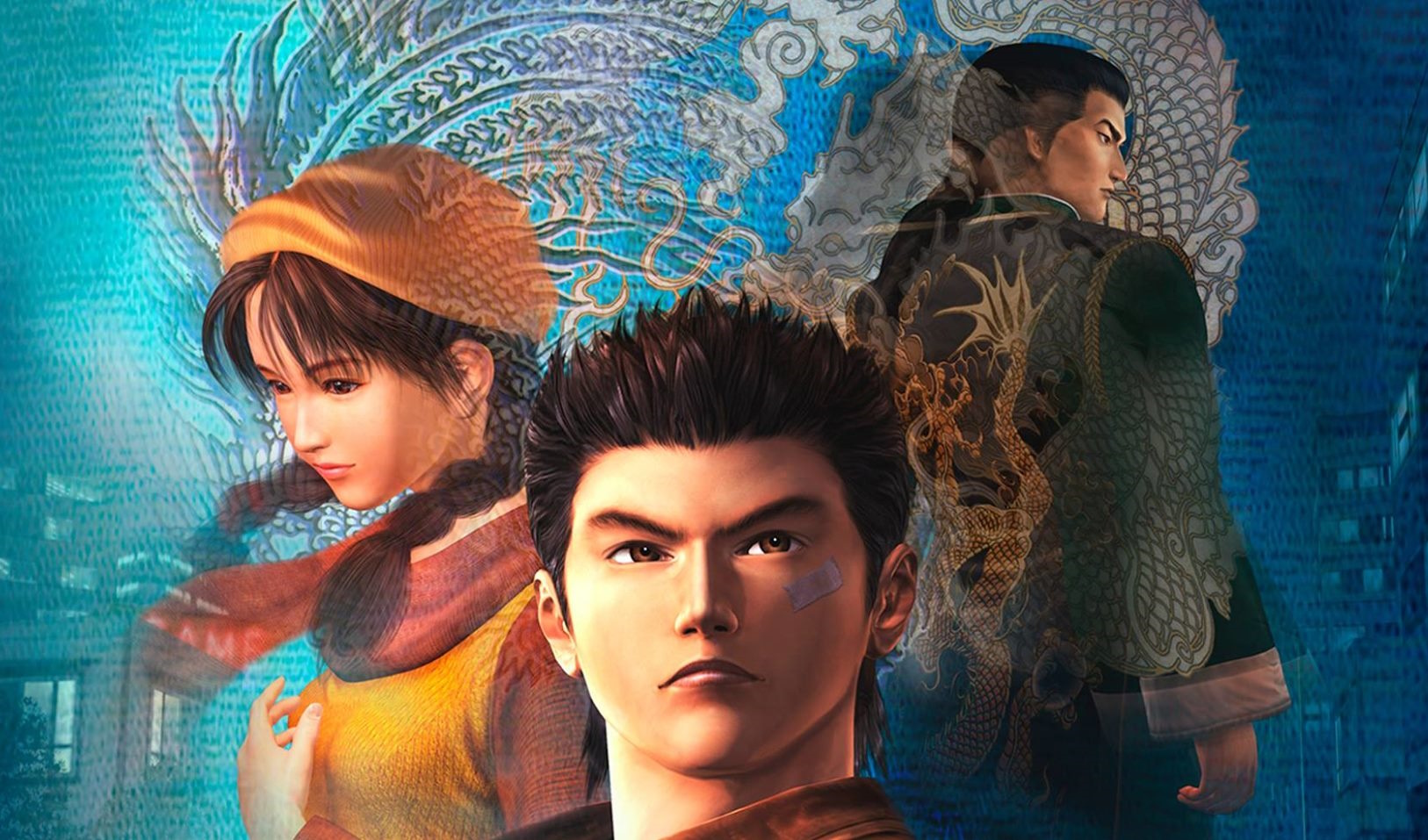

Image Credit: Shenmue Dojo on YouTube.

But all of that is for the birds. The trailer was a hoax, sure, and a fourth Shenmue game still feels out of reach right now. However, if the stars were to align and Shenmue IV ever did get off the ground, I have a few thoughts on what the game should look like.

First of all, the most important red line I have for Shenmue IV is the one that went unsaid in the 2010s with Shenmue III: this *needs* to bring the saga to an end. If there’s too much story left, too many chapters, and too much gameplay… well, figure out a way to cut it down. Have tighter levels instead of wide, open environments. Scrap mini-games and collectibles. Keep the game as tightly-focused on the core story as possible.

Cutting out content doesn’t mean losing *entire* chapters or one massive chunk of the story, either.

Let’s say, hypothetically, that there are five “chapters” of Shenmue left, according to Yu Suzuki’s original plans. Instead of having to totally scrap three or four of them, we could cherry-pick the most narratively-important parts from all or most of them, and build the game around those. Some settings might have to change – instead of chasing Lan Di to a new city, Ryo might have to face him in the smaller village where he already is, for instance. But this kind of shortened story *is* achievable.

The very generative A.I. that the hoaxer used to create the fake trailer could be really useful, too. If we’re cutting down gameplay, some story moments can be told via cut-scenes, instead, and the possibilities presented by generative A.I. are truly impressive. Given that YSNet is an independent studio that would have to work to a tight budget, I think the use of A.I. tools is an acceptable sacrifice. It’d be controversial in some quarters, as anything to do with generative A.I. is at the moment, but it wouldn’t be insurmountable.

To continue my hypothetical, instead of having to totally scrap Chapters 7 and 8 in order to get to the end of the story, maybe our condensed version of Shenmue IV would combine the mystery of 7 with the boss fight from 8, fill in some of the gaps in between 8 and 10 with cut-scenes and a small explorable environment, and then bring us to Chapter 10, which would be cut in half and take place across a smaller map. Chapter 11 – the final one – could be more or less complete, depending on how big it’s supposed to be, and might be able to re-use some of the environments from either Shenmue III or from earlier parts of Shenmue IV.

That’s how you cut down this kind of game. It isn’t about one massive removal, but a succession of smaller decisions, keeping levels tighter, content more concise, and the narrative on the rails.

It wouldn’t be totally true to the Shenmue style, and I get that. Some fans wouldn’t want to make that kind of sacrifice. But we’re more than six years on from Shenmue III, more than a quarter of a century on from the first game… and time’s a-ticking. How long are folks really willing to wait for a “perfect” version of Shenmue IV and V? As I wrote a couple of years ago: we mustn’t let “perfect” be the enemy of “good enough.”

Despite the hoax putting a cat amongst the pigeons in the fan community, and attracting a modicum of attention in the wider gaming press, I still don’t see a fourth Shenmue game happening, unfortunately. The interest just isn’t there with a wider audience, and without it, there’s no real prospect of an expensive single-player title making its investors much money. Even if the fan community could recreate the $7 million raised in the 2010s (which I *highly* doubt), that still wouldn’t be enough. And for YSNet, going to any investors seeking money for a game series that has failed three times and also produced an unsuccessful anime adaptation that was also cancelled? Yeah… you can see why they haven’t been successful, I guess.

If I can see anything positive to come from this hoax situation, it’s actually that generative A.I. might, in the future, be able to be used by fans to create an ending to this tragically-unfinished masterpiece. If Yu Suzuki can’t manage to make a new game, maybe one day we’ll at least get an outline of where the story was supposed to have ended up – and fans, perhaps using A.I. tools, will be able to convert that story outline into some kind of animated movie or even a game. The fact that the trailer was good enough to fool a lot of people – including some journalists – says more about how far generative A.I. has come in just a short couple of years than it does about the grassroots support for a new Shenmue game.

I’d be thrilled if YSNet were to announce Shenmue IV, don’t get me wrong. And I’m sure that Yu Suzuki still hopes, one day, to be able to finish his magnum opus. But despite the attention the trailer picked up last month, I don’t think it’s really done much to help that cause, and – as with any hoax, really – it’s done more harm than good to the fans. People got their hopes up for the first time in years, only to crash back down to earth hard when it turned out to be based on a lie.

Hopefully there won’t be any copycats, and hopefully folks will think a bit more critically if another supposed “leak” hits the internet. Because of how easy it is to use these generative A.I. tools, we all really ought to be careful and think critically about these kinds of things. A sign of the times, I guess.

I have a dedicated Shenmue page here on the website now. You can find it by using the menu above, or by clicking or tapping here. Now that we’re into Shenmue II’s big twenty-fifth anniversary year, I daresay I’ll be writing up my thoughts on that title before too long. And if I ever decide to play Shenmue III, I expect I’ll talk about that game here on the website, too. Though I personally doubt a fourth game is coming, I’m still crossing my fingers and hoping for the best. This hoax has been a big disappointment for a lot of people, and I don’t mean to add to that or stir the pot, but I wanted to air my thoughts on the future of Shenmue, since the fake trailer dragged it all up for me again. I hope this has been interesting – and not too depressing.

Shenmue I & II and Shenmue III are out now for PC, PlayStation 4, and PlayStation 5. Shenmue III Enhanced is due out sometime in 2026. The Shenmue series is the copyright of Sega, YSNet, and/or ININ Games. Some concept art courtesy of Shenmue Dojo. This article contains the thoughts and opinions of one person only and is not intended to cause any offence.