In the ’90s and early 2000s, I was a pretty big fan of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. The show felt fresh and different; taking horror villains and tropes but bringing them into a fun, modern setting. There was a great cast of characters, too, that changed and grew over time, and some well-executed longer arcs mixed in with plenty of episodic storytelling. There’s no doubt in my mind: Buffy was a great show.

I haven’t actually re-visited Buffy the Vampire Slayer since it was on terrestrial TV here in the UK. The final episode would’ve aired in late 2003, I guess, meaning I haven’t seen it in more than twenty years! Can I still call myself a fan of something two decades later? I don’t know… but I still consider myself a fan, at any rate.

So why are we talking about Buffy today? The answer is simple, unfortunately: Buffy the Vampire Slayer is the latest series to be targeted for a resurrection by its corporate overlords. They’re hoping to add more content to Hulu – an unsuccessful streaming platform. A Buffy reboot is in the offing… and honestly, I think it sounds like a terrible idea.

When interviewed about the reboot – which is still at a very early stage – Sarah Michelle Gellar likened the show’s revival to the likes of Dexter and Sex and the City. Y’know… those notoriously successful reboots that everyone just adores. Given that several members of Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s old cast have retired from acting (or couldn’t be part of a reboot for other reasons), I think a more apt comparison would be something like Frasier. That show, which also had its heyday in the ’90s, was revived with only one of its main characters returning. And, as anyone could’ve predicted, it flopped.

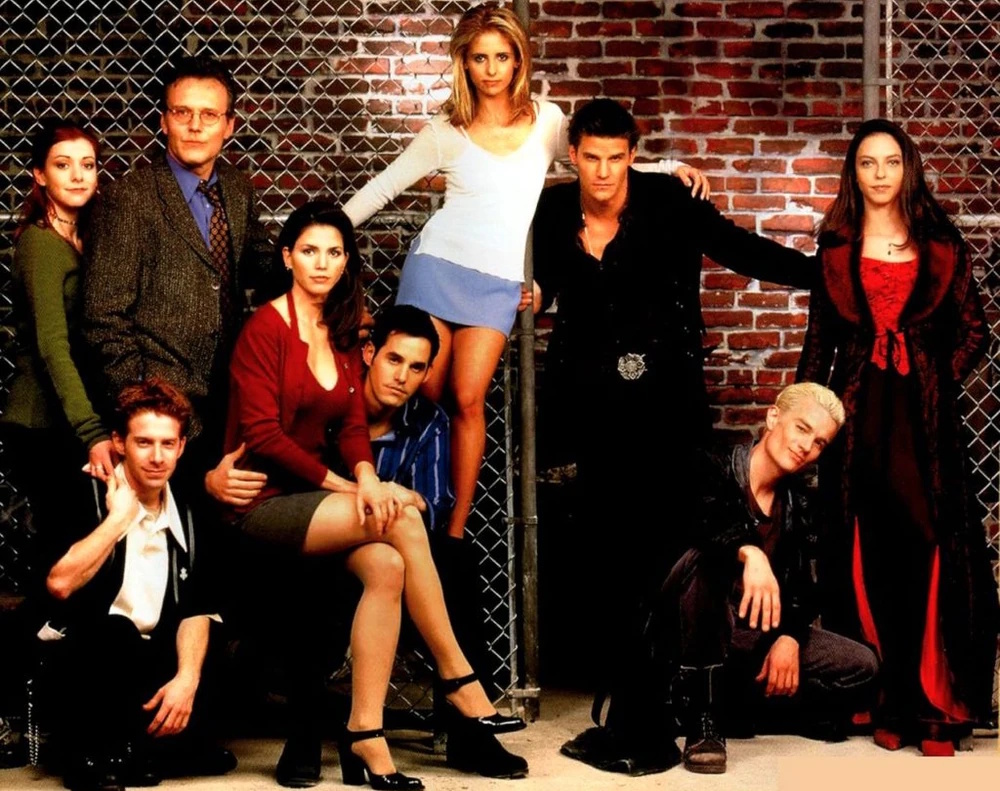

Photo Credit: IMDB/Getty

A reboot is not inherently bad in and of itself, but it has to be created for the right reasons. There have to be new stories to tell, something more to say, and a purpose beyond a corporate board and investors looking to make a quick profit. The streaming TV landscape is also oversaturated with attempted revivals of once-popular shows, as well as franchises trying to recapture their glory days. There’s much more limited room for manoeuvre for a Buffy reboot in 2025 than there might’ve been even a few short years ago.

If I recall correctly, Buffy’s seventh and final season came to an explosive end – but left the door ajar for potential future stories. But with many character arcs being complete, and with Buffy herself having literally been to hell and back, what kind of new adventures could she realistically get into? And with several characters dead and other performers no longer available, would fans be interested in half of a reunion? Would brand-new characters – who would need to be added to fill out the lineup – be as interesting or as welcomed by the returning fans that the reboot’s producers hope to entice?

There was a charm to Buffy the Vampire Slayer in its original form. It was something different on TV; soft horror that had a lot of the monsters but without crossing over into anything outright terrifying. It could be light-hearted and funny, but it was also serious enough in the way its characters were handled that moments of drama and tension still worked. The mix of episodic storytelling – a literal “monster of the week” – with ongoing story arcs and character development was also something rare on television at the time.

I don’t know how you replicate that today. With so many other horror shows on the air – from Stranger Things to The Terror and beyond – there’s a risk that Buffy the Vampire Slayer would seem tame or campy in comparison to some of those other offerings. Or, conversely, if Buffy was “updated” to be more violent and terrifying, really leaning into the horror angle, that the show would lose itself. Everything that made it unique would be erased; lost in the slop of big-budget streaming TV.

Some films and TV shows work in context – but they’re very much anchored to the time and place of their creation. You couldn’t reboot Cheers in the 2020s – not successfully, anyway. It’s an ’80s show with an ’80s theme and tone, and it wouldn’t work if you tried to transpose it to a brand-new decade. I can think of plenty of others, too – from British classics like Fawlty Towers to big-budget American shows like Seinfeld. Some story premises are genuinely timeless… but others aren’t.

Is Buffy the Vampire Slayer in that category? Is it a show so inherently linked to the turn of the millennium that it couldn’t work in the 2020s? I fear it might be – and while I could entertain, perhaps, the idea of a complete reworking of the concept, with a brand-new cast of characters taking on a horror series with episodic elements, I’m not sure bringing back some of the original cast will work, either. Twenty-five years ago, Buffy and her friends were at high school and university. Now… what will they be doing? They’re all going to be in completely different places in life, and that would also take something important away from the series – part of its core identity.

I’ve been wrong about these things before, and if this reboot does go ahead, then I’ll probably at least take a look at the trailers to see whether it seems like it has a chance of being any good. But to me, it feels like the kind of utterly soulless project born in a corporate boardroom, not a genuinely organic creation. To bring back a series that already ran to 144 episodes across seven seasons, you need to find a reason for doing so – and some way to tell new stories that weren’t possible last time. I don’t see what those stories could be, and without key characters who were essential to the original show, as well as the school setting which did so much to keep things grounded and relatable… what’s left?

I look at the failure of many recent reboots – Dexter, Frasier, Roseanne, and even, to some extent, the likes of Star Wars – and wonder what fans of Buffy will make of this idea. Returning to the core concept might have some merit to it, though even then I’d probably argue that a new series, with new characters, would be less restricting and a better way to go. But bringing back a handful of characters, now in their forties or older, to revive this high school drama? I mean… doesn’t it seem like a bit of a stretch?

Having said all of that, I was pretty excited in 2019 and 2020 for Star Trek: Picard – a series which brought back the fan-favourite character from The Next Generation for a new adventure. So perhaps the Buffy die-hards will be just as thrilled at the prospect of her return as I was for Jean-Luc Picard. And maybe, if the reboot is a success, it’ll be more a case of passing the torch from one generation of vampire slayers to another – and those new characters could go on to expand the franchise.

There is room, I would argue, for more episodic television in 2025, and that’s what Buffy used to be. The biggest horror and horror-adjacent streaming shows today are wholly serialised affairs: From, The Walking Dead, The Last Of Us, etc. And there’s room for a show inspired by the success of Buffy the Vampire Slayer to go back to the format’s episodic roots instead of telling one ongoing story. I don’t know whether this planned reboot even intends to do that… but I think there could be space for a series like that. If there’s a gap in the market anywhere, it’s on the episodic side of things.

So I guess that’s where I’m at when it comes to this idea. Part of me hopes that it won’t go ahead at all; Buffy was such a unique and singular show that tainting its legacy with an uninspired, corporate reboot – which will probably be squashed into eight-episode serialised seasons that don’t suit the format – would be a disappointment. If it does actually enter production, though, my only hope is that the creative team genuinely understand what made Buffy work in the first place and work on the reboot with that in mind.

Will I watch an all-new Buffy the Vampire Slayer if it gets made? I think, at the very least, morbid curiosity will push me to check out the trailers and see how it looks. But I’m not optimistic about a reboot in the current media environment, and it feels like a project that’s been sharted out by a corporate leader in a suit who’s desperate to find “content.” That doesn’t exactly inspire confidence in the potential quality of the revived series! If it looks good and reviews well, though… who knows? Never say never, I guess.

Honestly, though, I think I’d rather leave Buffy in the early 2000s where it belongs.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer (the HD remaster) is available to stream now on Disney+ in the UK, and Hulu in the United States. The series is also available on DVD. Buffy the Vampire Slayer may be the copyright of the Walt Disney Company, Mutant Enemy Productions, and/or 20th Century Fox Television. This article contains the thoughts and opinions of one person only and is not intended to cause any offence.